Book Review: Alexandria’s Sphinx — “Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography”

By Michael Londra

Unable to place the life and work of Constantine Cavafy in a holistic context, the biography can’t sustain momentum. Key points remain scattered, unintegrated.

Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography by Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jefferies. Farrar Straus Giroux, 560 pp, $40

Asked about fellow modern Greek-language poet Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933), Nobel laureate George Seferis responded, “Outside his poetry Cavafy does not exist.” A similar sentiment was expressed by Joseph Brodsky, another Nobel Prize-winner. Pinpointing why chronicling a poet’s life can be a challenge bordering on the impossible, Brodsky explained “real biographies of poets are like those of birds…in the way they sound…in twists of language…meters, rhymes, and metaphors.” In other words, poets are boring. Whenever confronted with “perfection of the life or the work” (as W.B. Yeats characterized it in “The Choice”), the latter wins out. As a result, any writer’s “real life” will be at a desk, rewriting the same sentence a thousand times—not scintillating fodder for biographers.

Asked about fellow modern Greek-language poet Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933), Nobel laureate George Seferis responded, “Outside his poetry Cavafy does not exist.” A similar sentiment was expressed by Joseph Brodsky, another Nobel Prize-winner. Pinpointing why chronicling a poet’s life can be a challenge bordering on the impossible, Brodsky explained “real biographies of poets are like those of birds…in the way they sound…in twists of language…meters, rhymes, and metaphors.” In other words, poets are boring. Whenever confronted with “perfection of the life or the work” (as W.B. Yeats characterized it in “The Choice”), the latter wins out. As a result, any writer’s “real life” will be at a desk, rewriting the same sentence a thousand times—not scintillating fodder for biographers.

Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jeffreys’s Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography is the latest proof of this contention. As Seferis noted, Cavafy poured every drop of energy and imagination into perfecting the corpus of over 150 poems on which his international reputation rests. Spending three decades as a government clerk, never moving from the same address above a brothel in the historically Greek quarter of Alexandria. Cavafy was the epitome of the poet as house cat. Naturally, readers of “The God Abandons Antony,” “The City,” “Ithaka,” “Waiting for the Barbarians,” “Caesarion,” and “Myris; Alexandria, A.D. 340”—stanzas that are staples of world literature—will be curious about the person who crafted them. E.M. Forster, Jackie Onassis, and W.H. Auden counted among his superfans. But, as Jusdanis and Jeffreys acknowledge, “this is one of the paradoxes of the Cavafy phenomenon: one of the most celebrated poets of the twentieth century, the most frequently translated Greek poet into English, has had few biographies,” most likely because of a “lack of interest” on the part of would-be chroniclers deterred by “the predictability…of the poet’s life itself.”

Indeed, the “facts of Constantine’s life are…unremarkable and very straightforward.” That said, Jusdanis and Jeffreys encountered other difficulties: the “physical absence of evidence, the gaps in his records, and our own discomfort with traditional narratives of life stories.” For these reasons, the authors opted to reinvent the wheel: “we decided not to follow a standard ‘birth-to-death’ chronological direction…[telling] a circular narrative through various thematic sequences.” This enabled them “to draw attention to the artificiality of biography as a type of writing.” As a literary artist, Cavafy would concur. Every “type of writing” is “artificial” because reality is mediated by language. Culture is what Picasso famously called the “lie that tells the truth.” Cavafy revelled in this paradox. For him, contrivance generates authentic meaning.

Instead of looking down on biography, however, by asserting the necessity for reengineering an exhausted genre, Jusdanis and Jeffreys could have followed Cavafy’s lead. Fully identifying with the “artifice” of those apparently dubious storytelling techniques, simply in order to transcend them. After all, the aim of every poet’s biography should be to enlarge the writer’s readership. If the discipline of biography is dead, how can it accomplish that mission? Overwhelmed by the magnitude of their project, the authors’ self-confessed “discomfort” with biographical narrative feels more like an admission of defeat. Partitioned into five sections—with an “interlude” on “Constantine’s Reading” between parts three and four—the book’s structure is reminiscent of a collection of essays. Unable to place Cavafy in a holistic context, momentum is never sustained. Key points remain scattered, unintegrated. Priorities are irregularly emphasized. For example, there is a cheat sheet of “Important People in C.P. Cavafy’s Life” and another detailed list of significant events. Yet there is no separate inventory that thumbnails Cavafy’s key poems and reinforces his accomplishments. Most of the “important” names are already sufficiently discussed. Further mention in a movie credits roll call at the end is overkill.

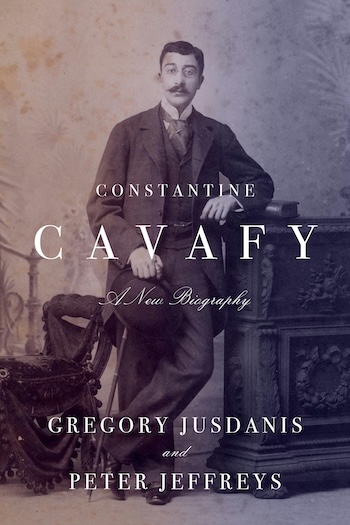

Constantine Cavafy in 1929. Photo: C.P. Cavafy Archives – Onassis Foundation

Breaking Cavafy into bite-sized morsels, Jusdanis and Jeffreys divvy the volume up into “The Cavafy Family,” “Alexandria: The Dreamscape,” “Friends,” “Living for Poetry,” finishing with “Cultivating Fame.” This “sensible-shoes” strategy ends up walking around its subject, afraid of walking up to him. Each chapter contains further subsections. Presumably these represent the authors’ individual labors, though there is no attribution to indicate who wrote what. There are repetitions—likely the outcome of two minds separately plowing the same biographical ground. It is a pity that Jusdanis and Jeffreys were not influenced by recent chronological attempts that explore — in illuminating prose — poets just as elusive as Cavafy, such as Richard Zenith’s Pessoa: A Biography and Heather Clark’s Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath.

Which is not to say that Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography does not contain good things. Both authors are scholars with a lot of valuable information to impart. But, because Jusdanis and Jeffreys are obsessed with producing a “definitive” account, readers might drown in a surfeit of details. Born to a rich mercantile clan in 1863 in Alexandria, Cavafy was seven when his father suddenly died and the family’s fortunes nosedived. His mother then packed everyone up and voyaged to London and Liverpool in the vain hope of resuscitating the family Egyptian cotton export business. They eventually detoured to Constantinople (now Istanbul) for three years once the 1882 British bombardment of Alexandria began. It is believed that it is in this city that Cavafy lost his virginity. Untethered from the constraints of bourgeois propriety in his exciting “urban finishing school,” Cavafy embarked on the sexual encounters with men—one-night stands, furtive love affairs—that informed his later lyrics.

Finally resettling back in Alexandria in 1885, Cavafy published his floridly Victorian first poems, supporting himself with a dreary career working in irrigation services. Jusdanis and Jeffreys don’t pull punches regarding the impact of colonialism on Cavafy: “the modest life he enjoyed in Alexandria as a civil servant depended on British hegemony in Egypt.” Colonialism did not bother him. He “was a liberal humanist, more sexually than politically progressive.” And while “Alexandria was…a Muslim city,” Cavafy’s “commanding knowledge of historical change…did not provide him with insights into the social transformation taking place…the Egyptian nationalism spreading” around him. Revolution was in the air. He was oblivious. Narcissistic (like many other poets), “Constantine was most happy…and true to himself in the Alexandria of his creation”—a decadent, decaying city of concealed desires and crumbling cosmopolitan façades whose wealth was guaranteed by the relentless oppression of the indigenous population.

Around forty, Cavafy’s verse changed. Evolving beyond the ostentatious style of his early efforts, he downshifted into a flat and detached tone better suited to a mature adult’s erotic and elegiac outlook. Cavafy scandalized his contemporaries by foregrounding queer sensuality: the biographers tell us that “while same-sex relations among men were not uncommon at the time, Constantine was different in naming this activity, in highlighting it as an identity.” In this sense, Cavafy’s achievement is trailblazing; he made history with his poetry. Indeed, he claimed that he would have been a historian if he hadn’t been a poet. Aficionado of disaster, failure, moments of disgrace, lost fragments, esoteric figures, and unheroic episodes, Cavafy cultivated Byzantine and Hellenic sources to stimulate his creativity. Driven by “gargantuan aspirations, a monastic focus on his craft, and a loveless existence,” he stands “absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe” (as E.M. Forster described him). He was an unclassifiable “Alexandrian sphinx,” comprised equally of “evocations, dreams, allusions, and feelings.” He operates—inscrutably—on the other side of “the barrier between reality and imagination.” Sadly, Jusdanis and Jeffreys posit that Cavafy’s executors purged his estate of outré material which might have shed more light on this “self-interested, self-involved” human riddle.

Cavafy is the first modern poet to go viral. Patrons and literary champions, the influencers of that day, made him. Personally handing out poems printed on broadsheets in his cramped, candlelit apartment to visitors invited because of the power they had to promote his work, he earned worldwide fame, counterintuitively, through word of mouth. Cavafy was a man who “recklessly risked it all and won.” Because of his bravery, Cavafy deserves a courageous biography. A volume less academically inhibited. One more spiritually aligned with the fearless, yearning heart that composed “The Bandaged Shoulder:” “When he left, I found, in front of his chair, / a bloody rag, part of the dressing, / a rag to be thrown straight into the garbage; / and I put it to my lips / and kept it there a long while— / the blood of love against my lips.”

Michael Londra talks New York writers in the YouTube indie doc Only the Dead Know Brooklyn (dir. Barbara Glasser, 2022). “Time is the Fire,” the prologue to his forthcoming Delmore&Lou: A Novel of Delmore Schwartz and Lou Reed is published in DarkWinter Literary Magazine. His Arts Fuse review, “Life in a State of Sparkle—The Writings of David Shapiro,” was selected for the Best American Poetry blog. He contributed six essays and the introduction to New Studies in Delmore Schwartz, out next year from MadHat Press. Additional reviews and poetry appear or soon will in Restless Messengers, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, The Fortnightly Review, Asian Review of Books, and The Blue Mountain Review, among others. He lives in Manhattan.