Film Review: “Weapons” — No Child Left Behind

By Nicole Veneto

What sets Weapons apart from other films utilizing a puzzle-box approach is Zach Cregger’s command of tone, a byproduct of honing his skills in sketch comedy.

Weapons, directed by Zach Cregger. Screening at AMC Assembly Row, Apple Cinemas, and other cinemas in New England

Children run into suburban darkness in Zach Cregger’s Weapons. Photo: Warner Bros. Pictures

It’s to Weapons’ benefit that it’s less whatever the hell “elevated horror” means now and more like something Stephen King wrote with cocaine whispering in his ear. This is either an endorsement or a warning, depending on your expectations. But there’s no question Weapons is from the same mind that reimagined Lincoln’s assassination as retaliation for his atrocious theater etiquette.

Zach Cregger and I go way back. Not much from my adolescence has survived into adulthood unscathed or without crippling shame. His sketch comedy troupe’s eponymous IFC series The Whitest Kids U’Know (2007-2011) would not pass current standards of political correctness, but remains a silly, nostalgic little comfort watch. Precious few things are as funny to me as “Motorcycle Mamas,” which ends on Cregger being wished out of existence by fellow Whitest Kid Trevor Moore clicking his heels in fatherly disappointment. So when Cregger reemerged with 2022’s bonkers horror hit Barbarian, I watched it as someone overly familiar with seeing him don bad girl drag and goof around with his pals. Yet even I didn’t anticipate a #MeToo allegory where legacies of abuse are embodied by an incest monster forcing unsuspecting Airbnb renters to suckle from a giant baby bottle.

In hindsight, Barbarian’s thematic heft may have given people the wrong impression about what kind of filmmaker Zach Cregger is.

There’s a chance Weapons isn’t the movie you’re expecting it to be. And that’s the lure. Cregger has already proven that shrouding your film in mystery doesn’t just retain the element of surprise — it’s good marketing. Barbarian’s success was in part because it withheld its narrative twists and turns, tantalizing potential audiences with a smattering of publicity images that provoked enough morbid curiosity to get them to the theater. A similar strategy has been applied to Cregger’s second feature (technically third if you’re counting Miss March — fourth if you include The Civil War on Drugs), the premise of which is neatly encapsulated by its tagline: “Last night at 2:17 am every child from Mrs. Gandy’s class woke up, got out of bed, went downstairs, opened the front door, walked into the dark …and they never came back.”

The aftermath of this tragedy finds the town of Maybrook turning the pitchforks on schoolteacher Justine Gandy (Julia Garner). To the parents, she’s either complicit or negligent, assumptions based purely on hearsay. Principal Marcus (Benedict Wong) doesn’t believe the condemnations; alcoholism aside, the only thing Justine is guilty of is caring too much. Guilt by proximity is more than enough for grieving father Archer Graff (Josh Brolin), who labels her a witch. Meanwhile, the police can’t turn up any substantial leads, but they aren’t conducting what you’d call an organized investigation, given that Officer Paul Morgan (Alden Ehrenreich) is too busy brutalizing displaced addicts like James (Austin Abrams) to search for any missing kids. Absent any institutional support, Justine and Archer launch their own separate investigations, which lead them back to the one child left behind: Alex Lily (Cary Christopher), whose home life presents a massive red flag conveniently overlooked by the community.

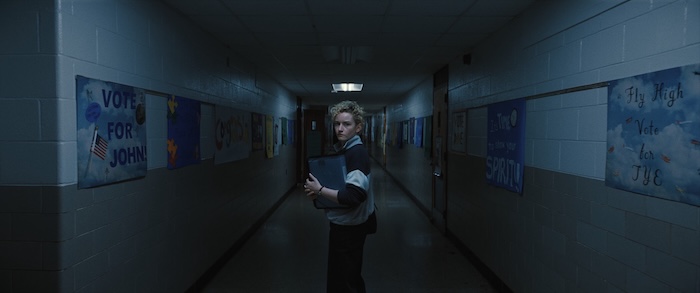

Schoolteacher Justine Gandy (Julia Garner) dreams of empty hallways in Weapons. Photo: Warner Bros. Pictures

As in Barbarian, Cregger utilizes a hairpin turn narrative structure that builds to a climax before passing the baton off to another character’s perspective. What sets Weapons apart from other films utilizing this puzzle-box approach is Cregger’s command of tone, a byproduct of honing his skills in sketch comedy. For as much as the film plays as a suburban drama about people grappling with an unexplainable loss (more on this shortly), the undercurrents of small-town paranoia eventually give way to Cregger’s absurdist impulses. What we least expect is often the funniest (and/or scariest) thing that could happen, à la “Motorcycle Mamas” or the Mother in Barbarian.

But what is Weapons actually about?

Well, a lot of things, depending on how much you read into it. Whether or not Weapons successfully commits to any particular idea comes down to what signifiers you’re willing to engage with. Cregger offers a lot of different imagery up for interpretation. The most affecting takes the form of a massive AR-15 floating in the sky. (Even he doesn’t know what to make of that.) Combine that with a title as confrontational as “weapons,” along with the empty classrooms and makeshift memorials featured in the opening minutes, and associations with school shootings seem de rigueur. Alas, this connection isn’t so much a red herring as it is one of several ever present strains of uniquely American evils haunting the film. A practitioner of David Lynch’s transcendental meditation, Cregger is drawing from our own collective psychosis about what’s harming our kids. The answer, it turns out, is where trouble always tends to brew.

(WARNING: This is your last chance to bail before I spoil Weapons.)

Like Barbarian, Weapons is about abuse. That the mystery unfurls into a folk horror-cum-Grimm’s fairy tale about how older generations weaponize children (and people) for their own ends is about as broad as Cregger’s social commentary gets. This is also where our ensemble dark horse emerges: Gladys (Amy Madigan, now the frontrunner for 2025’s most popular Halloween costume), Alex’s sickly aunt, who takes up residence at the Lilys’ home and unleashes the archaic forces Maybrook is unequipped to deal with. The witch hunt against Justine was barking up the wrong tree; a literal witch has commandeered the children in Alex’s basement.

At least that’s what I’ve landed on as the denotative meaning. Connotatively, Weapons is Zach Cregger’s way of processing his own unexplainable tragedy.

A little after 2 a.m. on August 7, 2021, mere hours after he and Trevor Moore signed off on a WKUK Twitch stream, Moore fell from his balcony and died in his driveway. (Note: Weapons opened for Thursday night preview screenings on August 7.) Moore wasn’t just Cregger’s creative partner, he was his best friend. Suddenly, he wasn’t there anymore. While Barbarian was in post-production, a shocked Cregger booted up a Word document and began typing the child’s monologue that opens the film. As he told Vanity Fair: “Something precious is gone, and everyone is left to just deal with it. That was the jumping-off point.”

Whatever deeper social commentary Weapons offers, the fact that the movie is so funny is what makes it first and foremost an ode to Moore’s memory. The Whitest Kids spirit is all over this thing, hence why it functions more as wildly entertaining popcorn horror than it does as razor-sharp social critique in the vein of fellow sketch-comic-turned-horror-director Jordan Peele. Ehrenreich’s mustached Officer Morgan and his fentanyl freakouts are akin to the kind of characters Moore frequently played in WKUK skits. And the ending — oh the ending! — pays off in some truly grotesque, over-the-top slapstick that IFC’s standards and practices would have held several emergency meetings over.

Funny as they still are, rewatching old Whitest Kids episodes or WKUK streams exudes an uncanniness; it is like seeing a ghost captured on screen. That Moore’s memory and influence are figuratively conjured in warp and woof of Weapons is the real key to the mystery. Grappling with being one of the Whitest Kids left behind, Cregger has produced a narratively sprawling, technically accomplished horror ride in which grief gives way to absolute lunacy. It’s exactly what Trevor would have wanted.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and her podcast on Twitter @MarvelousDeath.