Book Review: “Ne me quitte pas” — A Guide to a Song That Crosses Borders

By Jim Kates

This splendid book is a love letter and a dissertation, almost a song in itself.

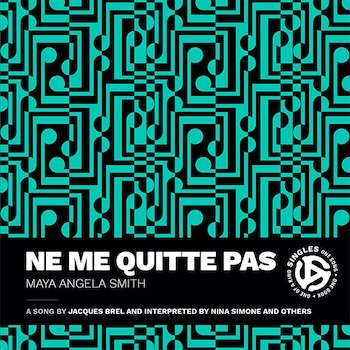

Ne me quitte pas: A Song by Jacques Brel and Interpreted by Nina Simone and Others by Maya Angela Smith. Duke University Press, 152 pages, $19.95

Maya Angela Smith’s Ne me quitte pas is a book you cannot read without engaging your ears as well. It begins with a young Black woman listening to her parents’ record collection while she’s discovering the French language. You will want to listen to what she was listening to, although I expect you already know it — Nina Simone’s cover of Jacques Brel’s song that gives the book its title.

Maya Angela Smith’s Ne me quitte pas is a book you cannot read without engaging your ears as well. It begins with a young Black woman listening to her parents’ record collection while she’s discovering the French language. You will want to listen to what she was listening to, although I expect you already know it — Nina Simone’s cover of Jacques Brel’s song that gives the book its title.

As a young white man growing up listening both to French chanson and to Simone’s unique classically trained jazz, I did not notice the transgressive assertion of the Black singer’s appropriation of European white tradition. The future Dr. Smith, now a professor of French at the University of Washington, did. It affected her sense of herself in the world. And this has led her to write about that one song as the center of a conversation about music, lyrics, language, translation, race, and gender identity:

“Ne me quitte pas” hasn’t just moved from one voice to another through covering or from one language to another through translation. It has also crossed borders of media and genre to find a home in film, theatre, and various types of performance art. These border crossings require adaptation of the source text to fit in a new context through a complete process of shifting materials.

Or the book properly begins with the Belgian singer Jacques Brel himself, who released “Ne me quitte pas” when he was 30 years old, in 1959, and who became associated with the song in an emotionally complex way that culminated in a 1966 performance. According to a review of Smith’s book in The Times Literary Supplement, “Édith Piaf was apparently unimpressed by his lack of decorum and manliness: ‘Un homme ne devrait pas chanter des trucs comme ça!’ (‘A man shouldn’t sing things like that!’).” From the beginning, the song seemed destined to cross boundaries of emotional and gender acceptabilities.

Simone picked up on this, learning the lyrics even before she knew enough French, in that way making it especially her own. And that is how I first heard it, like Smith. Simone herself later left the United States to live and die in France, joining a roster of Black artists that included Josephine Baker, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and Gordon Heath, among others, and for the same reasons.

The American popular poet Rod McKuen translated “Ne me quitte pas”into English and Shirley Bassey, a biracial Welsh singer, introduced that slightly watered-down version, “If You Go Away,” to new audiences and interpretations. Maysa Matarazzo folded it into Pedro Almodóvar’s film Law of Desire. In one incarnation or another,”Ne me quitte pas” has graced a number of different occasions; it has been featured in drag shows and in the Cirque du Soleil. Written in a man’s voice, the song has most often been re-envisioned by women, who sometimes alter the gender, sometimes not.

The American popular poet Rod McKuen translated “Ne me quitte pas”into English and Shirley Bassey, a biracial Welsh singer, introduced that slightly watered-down version, “If You Go Away,” to new audiences and interpretations. Maysa Matarazzo folded it into Pedro Almodóvar’s film Law of Desire. In one incarnation or another,”Ne me quitte pas” has graced a number of different occasions; it has been featured in drag shows and in the Cirque du Soleil. Written in a man’s voice, the song has most often been re-envisioned by women, who sometimes alter the gender, sometimes not.

Smith discusses all of this and more with sensitivity and depth in the space of a hundred pages. She writes from the inside out, whether she is examining the words (‘Ne me quitte pas’ is a lyrical tour de force. It’s one of Brel’s most literary, poetic, and intimate songs, from the [literary] allusions … to the … metaphors of impossibility that form the song’s backbone”) or probing the music (“The same chords repeat through most of the song … with each chord taking up a full bar. However, the harmonic rhythm accelerates during the most poignant sections….”).

In commenting on the musical Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris (in which “Ne me quitte pas” is the only song sung in the original French), Smith notes Brel’s acceptance of the changes made by the writers of the revue: “Brel’s response suggests an understanding of the importance of recontextualization and how a text must transform to better reflect a new context influenced by language, culture, and audience.”

Smith amplifies that understanding. So pull up a chair, fire up your favorite streaming service (if you don’t already have an encyclopedic library of recordings), and immerse yourself in “Ne me quitte pas” in all its manifestations while you read this book, a love letter and a dissertation, almost a song in itself.

J. Kates is a poet, feature journalist, and reviewer, literary translator, and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a nonprofit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book of poetry is Places of Permanent Shade (Accents Publishing) and his newest translation is Sixty Years Selected Poems: 1957-2017, the works of the Russian poet Mikhail Yeryomin.