Film Review: “Made in New Jersey” — A Fabulous Trip in the Cinematic Way-Back Machine

By Betsy Sherman

Before Hollywood became synonymous with the movies, Fort Lee, New Jersey, just a ferry ride across the Hudson from Manhattan, welcomed and supported the motion picture companies turning out product for the nation’s nickelodeons and cinemas.

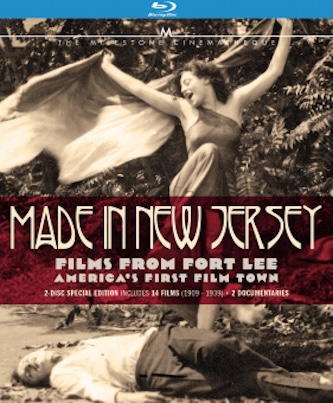

Made in New Jersey: Films from Fort Lee, America’s First Film Town. Two-disc Blu-ray available to purchase from Kino Lorber’s Milestone Cinematheque.

Those angels of film rediscovery and restoration, Milestone Film & Video, illuminate a fascinating chapter of early American film history with their new two-disc Blu-ray set, Made in New Jersey: Films from Fort Lee, America’s First Film Town . Before Hollywood became synonymous with the movies, this handsome suburban city, just a ferry ride across the Hudson from Manhattan, welcomed and supported the motion picture companies turning out product for the nation’s nickelodeons and cinemas. This journey in the way-back machine contains many delights, some staged and some as part of the photographic record of America from 100-plus years ago.

Those angels of film rediscovery and restoration, Milestone Film & Video, illuminate a fascinating chapter of early American film history with their new two-disc Blu-ray set, Made in New Jersey: Films from Fort Lee, America’s First Film Town . Before Hollywood became synonymous with the movies, this handsome suburban city, just a ferry ride across the Hudson from Manhattan, welcomed and supported the motion picture companies turning out product for the nation’s nickelodeons and cinemas. This journey in the way-back machine contains many delights, some staged and some as part of the photographic record of America from 100-plus years ago.

Curated by film historian Richard Koszarski, author of Fort Lee, the Film Town, the set contains 14 films made in Fort Lee between 1909 and 1939. The bulk are silent shorts made by directors including D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett before they moved west. The 1939 feature is an example of New Jersey’s attractiveness for independent producers serving niche markets, even into the age of sound films: Edgar G. Ulmer’s Ukrainian-language Cossacks in Exile. Also included are a 2015 documentary, The Champion: A Story of America’s First Film Town, chock full of archival materials, then-and-now shots and comments by scholars; Ghost Town: The Story of Fort Lee, an elegiac 1935 documentary showing the ruins of the mostly abandoned studios; and an informative 20-page booklet. Hats off to the institutions in the Garden State (such as the Fort Lee Film Commission) that have worked for decades to preserve these valuable materials. Another tip of the hat to the composers who wrote customized scores for the silents.

Eighteen-ninety-three saw the building of the first film studio, Thomas Edison’s Black Maria in West Orange, New Jersey. Fort Lee became one of the early 20th century outposts in which the art, science and business of cinema were being invented. Disc one, named Before Hollywood 1909-1913, showcases some of the innovations of that era. For example, it was only then that movie actors’ names became known to the public. Among the early studios that settled in Fort Lee are Biograph, Éclair, Champion, Victor, Kalem, Vitagraph, Keystone and Pathé. Later, more familiar names—Universal, Paramount and Fox—filmed in Fort Lee.

The earliest films here are a couple by David Wark Griffith, working for Biograph in Manhattan but filming exteriors in Fort Lee. His 1909 The Curtain Pole is 13 minutes of zaniness, a quality associated more with its star, Mack Sennett, than its director. Sennett (wearing a ridiculous false nose) plays a Frenchman who inadvertently breaks a wooden curtain rod before a party is to begin. With good intentions, he offers to pop out and buy a replacement. Unfortunately, he goes to a bar before the hardware store. Holding the long, thin pole horizontally, he “accidentally” knocks down pedestrians and bashes everything on each side. When he gets in a horse-drawn buggy, more mayhem ensues (trick photography produces some of the laughs). After pratfalls galore, the victims chase him. A passel of extras running past the camera can’t help giving the lens a glance and a grin.

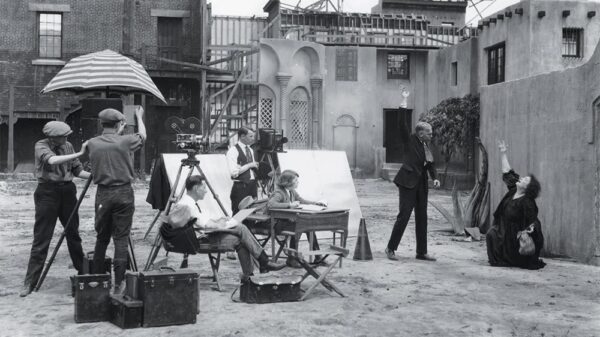

A film backlot at Fort Lee, New Jersey. Photo: NJ Motion Picture and TV Commission

The 15-minute The Cord of Life has a different mission: in an effort to create suspense in a community of Italian immigrants, a bad cousin (tagged in the intertitles as a “shiftless Sicilian”) attempts revenge on his good, family-man cousin. He puts the cousin and wife’s baby in a life-threatening situation: placed in a basket that’s hung outside the window by a cord of rope. The cross-cutting among all the parties involved must have really gotten the audience going. A nifty stunt makes all well. Some nice visual compositions are a credit to the eye of cinematographer G.W. “Billy” Bitzer.

The 31-minute Robin Hood, made in 1912 by Éclair, is the oldest extant film depicting this hero. The movie was restored from a nitrate print, and shows damage along the sides of the picture frame. But it’s still good-looking, with green, red and blue tinting according to the type of scene. It’s the familiar tale, with Robin and his band protecting the people from the cruel aristocrats in the absence of King Richard the Lionhearted. The focus is on trying to spring Robin’s true love Maid Marian out of her father’s house, since Dad wants to marry her off to stuffy old Guy de Gisborn. Locations include the forest, a tavern, and a high stone wall for rappelling. There’s creative camera trickery, and cross-dressing, as one of the Merry Men puts on Marian’s clothes to distract the bad guys (and gets a kiss from Marian’s father).

A scene from 1910’s The Indian Land Grab.

A short from Champion, The Indian Land Grab (1910), has an eyebrow-raising take on American history. It opens in the woods, as a generically costumed Indian chief decries the perfidy of the American government regarding its treaty with the tribe. He declares he’s going to Washington, D.C., to demand justice. The scene switches to flimsy interior sets of the halls of power. A politician tells his grown daughter to distract (nudge-nudge wink-wink) the chief while the “land grab” bill is being passed. She falls for him, grows a conscience, and secures the tribe’s land rights from the president himself. According to the booklet notes, “Reviewers at the time applauded the film’s exposure of governmental abuse of Indian rights but found its depiction of inter-racial romance ‘offensive’ and even ‘repugnant.’”

Victor Film Company was the first to devote itself to moviemaking for one particular star: the beautiful and energetic Florence Lawrence. By the time of the two enjoyable 1912 comedies included here, she had made scores of films for Griffith and others (she was the first Biograph Girl, preceding Mary Pickford). Not Like Other Girls was directed by Flo’s husband and business partner, Harry L. Solter. Plot is less important than buzzy high spirits as her character plays impetuous, unladylike tricks on the son of the man to whom she’s a ward (Owen Moore). Flo’s Discipline pairs her again with Moore. She’s the principal’s daughter at a boys’ school who uses clever (if fairly sadistic) means to impose order on the rebellious kids.

A scene from 1912’s Mack Sennett comedy A Grocery Clerk’s Romance. Photo: MUBI

Rambo’s hotel, where many of the movie folk stayed and dined, was often used as a film location. We rejoin Mack Sennett after he left Griffith and established the immortal Keystone studio (of the slapstick Keystone Kops and Bathing Beauties). His 1912 A Grocery Clerk’s Romance is nuts. In it, a rascal (or romantic?) played by Ford Sterling charms a married woman by taking over her laundry chores. Her shamefully lazy husband is driven away to where three ne’er-do-wells have a bomb with which to blow him up, so Sterling can immediately marry the newly minted widow. Rambo’s can also be seen in a couple of New Jersey Westerns. There She Goes (Pathé 1913) is a fun little romance/chase picture set in and around a delicatessen owned by a gruff German who’s in a losing battle to keep his daughter away from her cowboy suitor. Look for the abundant old-timey product placement. The peachy A Girl of the West (Vitagraph 1912) is carried by its hard-charging women. Young Polly (Lillian Christy) hangs out with the boys; she can ride with the best of ‘em. When she overhears Scar-Face Bill relate his plot to steal a horse for which a lucrative sale is in the works, she sets out to foil him. There’s an exciting horseback chase (shot in Englewood Cliffs, NJ) between Polly and Dance-Hall Nell (Helen Galvin), Bill’s accomplice. The cowboys come to Polly’s aid and shout her praises (“Hooray! She’s got pluck!”).

That predecessor of the femme fatale, The Vamp, was taking shape as an archetype. Kalem Studio, for The Vampire (1913), cast Alice Hollister as their man-eater. The 39-minute film was directed by Robert Vignola. Even then, its opening passage was a creaky cliché. Farm-dwellers Harold and Helen agree that Harold will go to the city to earn enough so they can marry. The rube gets an office job where he proves to be a good worker—until, at a fancy restaurant, he meets the seductive Sybil. They end the night at her apartment, and the scene fades out on a clutch. Sex and intoxicants take over the poor boy’s life, and he’s fired. Helen, who tries to find him, fights her own battle against the sinful metropolis.

Turn-of-the-century female empowerment: the “Vampire Dance” from 1913’s The Vampire. Photo: WikiMedia

But forget about Harold, Helen and Sybil—The Vampire boasts a performance of Bert French and Alice Eis’ magnetic “Vampire Dance.” In a clingy dress, with bare limbs, Eis is dynamic and feral as she plays spider to French’s fly and drains the life out of him (some may call it murder, but her face reads empowerment). She foreshadows the 20th century, while the rest of the movie is stuck in the 19th. The dance is meshed into the film in a bizarre way—it’s supposed to be happening onstage in a theater, but it’s actually happening outdoors among trees and vegetation, in the sunlight and wind, the better to highlight its play of animal desires. Vampire locations include Hackensack, Cliffside Park, and the recently built Penn Station.

The second disc, After Hollywood, contains works made in the years after Hollywood had emerged as the movie capital. The 61-minute 1918 The Danger Game is a big step forward from the shorts on disc one. The acting is more naturalistic and the comedy more subtle and sustained. Directed by Harry Pollard (not to be confused with Snub Pollard) for the Goldwyn studio, The Danger Game stars the wonderful Madge Kennedy, a big-eyed Broadway comedienne whom Samuel Goldwyn put to work in Fort Lee. Kennedy’s character, sheltered Long Island rich girl Clytie, is a more naïve version of the flappers who would rule the 1920s. The wannabe-Bohemian has just published (with Daddy’s money) a novel about a society girl who becomes a burglar. Motivated by a review that mocks the book’s credibility, she breaks into an apartment—not to steal, but to powder her nose. She’s arrested and mistaken for the thief “Powder Nose Annie.” After some colorful scenes in jail, she’s strung along by a reporter (Tom Moore) who encourages her to think he’s a “fellow” criminal. Kennedy has an engaging, low-key comedic style: she arranges her facial features so that Clytie’s thoughts and emotions bubble up from within, seeking free expression after so many years of repression.

Madge Kennedy in a scene from The Danger Game. Photo: WikiMedia

The set’s only sound feature, Cossacks in Exile, recently received a 4K digital restoration, sourced from a nitrate print. This filmed operetta has been available on home media, but with insufficient subtitling—none for the songs! The restoration, thankfully, has been fully translated, with text based on the 1937 English libretto plus research conducted by Dr. Vitaly Chernetsky.

The 1939 film—set in 1775—was made when Ukrainian exiles longed for the end of Soviet interference with their homeland. But it takes on a new resonance during the years of Putin’s war in Ukraine. It depicts a Russian invasion and the ensuing carnage. There’s a line about “a Moscow yoke upon my shoulders” and an officer asks, “Shall we forfeit our self-government? Never!”

The story of the film’s making has plenty of drama itself. During the 1930s, there were close to a million Ukrainian immigrants in North America. In Canada, dancer Vasile Avramenko became an avatar of folk culture by opening a string of Ukrainian music and dance academies. The impresario had the chutzpah to want to celebrate his nation of origin in the film medium, with which he had no experience. As there was no Canadian film industry at the time, he aimed to film in the U.S. He conducted a years-long grassroots financing campaign, selling shares among Ukrainian groups and individuals (a list of investors includes “farmer,” “carpenter” and “shoemaker”).

Avramenko met up with the now-legendary director Edgar G. Ulmer, a Jewish émigré from the Austria-Hungarian Empire, just as the latter was forced into working freelance. Ulmer had been blackballed in Hollywood, after making the great Universal horror picture The Black Cat, for running off with the wife of the studio head’s nephew. Ulmer’s next phase was making films in the New York-New Jersey area for minority audiences. These would include two Ukrainian-language films for Avramenko and four Yiddish-language features for other companies. Ulmer spoke neither Yiddish nor Ukrainian.

The partnership’s first result was an adaptation of the operetta Natalka Poltavka. It was filmed in 1936 on a farm in Flemington, NJ, and shown in 1937 to ethnic audiences. Avramenko oversaw the authenticity in language, singing, dancing, costumes and accoutrements. Ulmer placed the characters in natural settings and applied his experience in film and theater. Ulmer would direct Cossacks in Exile while at the same time making his Yiddish film The Singing Blacksmith. For this feat, he constructed both a Jewish shtetl and a Ukrainian village with an onion domed church.

Ulmer was admired for his ability to squeeze the most out of a shoestring budget. Not wanting to repeat himself and use the Flemington farm, he searched for a new location. However, with the rise of xenophobia in the U.S., few landowners wanted to host Ukrainian or Jewish showfolk. Ulmer found pastoral perfection on the grounds of the Little Flower Monastery in Newton, NJ. It happened to be located between Camp Nordland of the pro-Nazi German-American Bund and a nudist camp. Happily, the leader among the Benedictine monks welcomed the productions onto the grounds and even offered his monks to guard the sets overnight. Ironically, he and Ulmer conversed in German.

Moishe Oysher in The Singing Blacksmith. Photo: The National Center for Jewish Film

Top billing for the film went to Ukrainian singer Maria Sokil, who happened to be touring North America. One of Ulmer’s headaches was that he had to film all her scenes in June, as she was due back in Europe. Shots of her would then be cut into the picture. Shooting wrapped in September of 1938.

Cossacks is based on the 1863 operetta Zaporozhetz Za Dunayem by Seman Hulak-Artemovsky. It portrays the destruction of the Zaporogian Sich, a Cossack military stronghold, by Russia’s Catherine the Great, and the expulsion of the Cossacks to Turkey. The movie opens with a rousing song by a male chorus over visuals of galloping troops. A ghostly, superimposed bandura player called “the ageless bard of his race” is a sort of narrator. The men stationed at the fortress have families in the nearby village. Two couples are introduced. Odarka (Maria Sokil) and Ivan (Michael Shvetz) are the bickering married couple, Oxana (Helen Orlenko) and Andrey (Alexis Tcherkassky) the youthful hope for the future. It’s learned that the Empire wants to press the Zaporogian Cossacks into service. The Cossacks refuse, so the Russians burn the fortress down (the film was hand-painted so that the flames are orange).

The director creates a powerful tableau in a scene after the Russian attack. The elderly Cossack commander, on his way to exile in Siberia, bemoans his fate and that of his people. Shot from a low angle, next to a stone cross, he asks God to “return us to glory, to our freedom. Break our chains.”

The survivors cross the sea to exile in Turkey. This section of the film is tinged with nostalgia and yearning. There’s a lovely sequence in which the maternal Odarka, seated barefoot with Oxana and another young woman by the river’s shore, sings about the Danube. Ulmer seems more invested in the emotional pull of the operetta than in its passages of comic relief centered around the carouser Ivan. In a lengthy subplot, the Turkish sultan, amused by the boastful Cossack, plays a prank on Ivan that includes entry into his harem. The humor here is corny and full of stereotypes (I hate to say it, but Ulmer made an entire harem comedy in 1952 called Babes in Bagdad).

A scene from Edgar G. Ulmer’s Cossacks in Exile. Photo: Kino Lorber

A gratifying consequence of the fully translated libretto is that the lyrics give us insight into the women characters. Sokil is radiant as she sings songs both poignant and playfully bawdy (she’s less capable in the peasant-humor scenes with Shvetz). Ingenue Orlenko also shines as she trills longingly for her lover, who is in danger.

Avramenko’s loyal legions traveled to the location from all over Canada and the U.S. to help out behind and in front of the camera. The dance scenes are fabulous—with closeups of villagers of all ages intercut into them—as are the embroidered costumes and hairstyles. Ulmer made the most of the gorgeous scenery.

There’s one sight in particular in Cossacks that wouldn’t be seen in a Hollywood movie of its era: a married couple who sleep in a double bed rather than twin beds. The all-powerful Production Code made that taboo. But this being an independent production, and Canadian, it went under the radar. Hooray for Joizy!

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.