Book Review: “Mark Twain” — The Life of a Champion of Liberating Irreverence

By Jonathan Blumhofer

At its best, Mark Twain emerges in this biography as much a live wire as ever: brash, outspoken, and overflowing with exasperating contradictions.

Mark Twain by Ron Chernow. Penguin Press, 1174 pp.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, aka Mark Twain, didn’t make it easy for his future biographers. Not that he tried to be especially difficult — so far as we know. But the man had thoughts, some profound, many irreverent, not a few misguided, on virtually every subject under the sun. Though his major books total only about 15 volumes, Twain’s speeches, editorials, lectures, short stories, letters, and aphorisms seem endless. Add in his journalistic efforts and you’ve got an extraordinary body of work, not all of which has survived intact.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, aka Mark Twain, didn’t make it easy for his future biographers. Not that he tried to be especially difficult — so far as we know. But the man had thoughts, some profound, many irreverent, not a few misguided, on virtually every subject under the sun. Though his major books total only about 15 volumes, Twain’s speeches, editorials, lectures, short stories, letters, and aphorisms seem endless. Add in his journalistic efforts and you’ve got an extraordinary body of work, not all of which has survived intact.

And this is before you get into his dizzying experiences as a (mostly failed) businessman and investor, his complicated family life, his legion of friends and acquaintances, and the extraordinarily varied circles in which he lived and moved for more than 74 eventful years. No wonder his life is Ground Zero for the ambitious biographer.

Now the Twain bug has bitten Ron Chernow, who is no stranger to the giants of American mythology. His bibliography includes books on the house of Morgan and John D. Rockefeller. Alexander Hamilton inspired one of this century’s greatest musicals and Chernow’s life of George Washington netted the author a Pulitzer Prize.

Even so, there’s a sense, as one wades through Mark Twain, a magnificent doorstopper of an opus, that Chernow’s met his literary match. Not because of a lack of information — the tome’s packed with facts, sometimes shovelfuls by the page — or because of subpar writing.

Rather, Mark Twain’s biggest issue is its assumption that one of the most combustible personalities in American history can be constrained (“sivilized,” if you will) to fit within the confines of a traditional, blow-by-blow narrative. He can’t. And, as a result, Chernow’s form and content occasionally are at loggerheads. Working through this tension, especially over the book’s first half, can become unrelenting. On occasion, readers may feel as if they are wading across the Mississippi at flood tide.

That said, the larger undertaking, though it involves some curious elisions and concisions — Twain’s Mississippi River piloting days, for instance, get unexpectedly short shrift — is hardly a misfire. At its best, his writing, which draws extensively on letters and diaries, ensures that Twain emerges as much as a live wire as ever: brash, outspoken, and overflowing with exasperating contradictions.

Take the subject of race. On the one hand, Twain was far more enlightened on the topic than many white Americans of his day and more than a few of ours. Born into a slave-holding family, he came to see the evils of the “peculiar institution” early on and passed his remaining decades becoming an increasingly outspoken advocate for racial and cultural tolerance as well as an opponent of imperialism.

Yet the road he traveled was hardly straight or level. Jingoism and anti-Catholic (and -Arab) bias pepper The Innocents Abroad, Native Americans and Mormons are freely denigrated in Roughing It, and Jim shows up as a minstrel show-worthy caricature in Tom Sawyer Abroad. Twain’s fawning over Queen Victoria’s appearance at her Diamond Jubilee in 1897 was worthy of the most Anglophilic propagandist.

1870 edition of Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad

Even as his thinking on race and empire grew in scope with age — Twain was justly proud of the uproar he caused in late-1890s Vienna by taking public stands against anti-Semitism, and his indifference toward Native peoples softened over his last years — he was sometimes willing to pull his punches, most frustratingly on the subject of lynching.

Privately an outspoken opponent of the practice, Twain publicly kept his powder dry as racial violence flared across the United States around the turn of the 20th century. His explosive essay on the topic, “The United States of Lyncherdom,” didn’t appear in print until 1923, and then in bowdlerized form. The writer’s reluctance to air these “unvarnished views,” Chernow notes, was a major missed opportunity.

Twain was no less vocal in his contrarian takes on organized religion, though, again, the most vitriolic of those pieces were only published decades after his death. Twain’s skepticism stemmed, initially at least, from his mischievous nature, though, in time, bitter personal and professional blows cemented a nihilistic worldview. (That his wife, Livy, was a devout Christian and his closest friend, Joseph Twitchell, a Presbyterian minister, are two of the delightful ironies of Twain’s life story.)

The sheer breadth of his writing on the subject is enormous, running the gamut from the riotous skewering of the pious boobus Americanus in The Innocents Abroad to the cold, bitter logic of the posthumous Letters from the Earth. In between one finds wit, nuance, and pathos (The Diaries of Adam and Eve) as well as a deep and cynical understanding of how ritual and public religious practice often work in tandem (The War Prayer).

Much of Twain’s antireligious fervor also derived from his witnessing injustice and unmitigated suffering — sometimes perpetrated in the name of God — both within his family and during his extensive travels. Those things roused in him a kind of righteous ire.

Yet, as Chernow thoroughly demonstrates, this wasn’t always a positive force: the man had a volcanic temper and a seemingly limitless capacity for revenge. Virtually everyone who crossed him — or didn’t but Twain imagined had — felt his wrath. He fell out with doctors, lawyers, publishers, business associates, landlords, relatives, and more. Even the deaths of some of those (like his former publishing partner Charles Webster) didn’t calm his spirits.

The one person who could always assuage the worst angels of Twain’s nature was his wife, Livy. Their devotion to one another across courtship and 34 years of marriage forms a touching counterpoint to the upheaval that defined much of the rest of Twain’s life. Though she had more cause than most to castigate him for his failings, especially economic mismanagement — he squandered his substantial earnings and much of her considerable inheritance in a series of reckless investment schemes in the 1880s — she never did. (Livy wasn’t exactly a model of fiscal restraint, either; she and Twain seemed congenitally incapable of holding back when it came to procuring material items, especially for their sprawling Hartford mansion.)

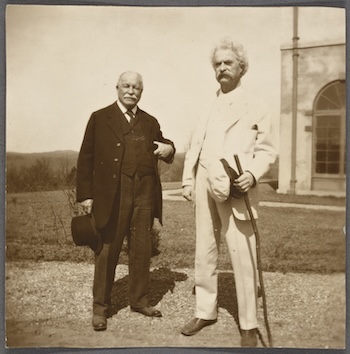

William Dean Howells and Mark Twain in Redding, Connecticut. October 1908. Photo: NYPublic Library

Their family life was, for a while, idyllic, with the couple’s three daughters — Susy, Clara, and Jean — passing sheltered, uneventful childhoods in Hartford. But, as the bottom fell out of the family’s finances, the whirlwind consumed the Clemens women. First, Livy was diagnosed with heart disease. Then, Susy, who was attending Bryn Mawr, developed a strong romantic attachment to a fellow female student. How much Twain and his wife knew about this attraction remains in dispute, but Susy was quickly whisked off to Europe with the rest of the brood, where the cost of living was cheaper.

Still residing abroad in 1895, Twain filed for bankruptcy and, at Livy’s insistence, agreed to repay his creditors in full, undertaking an arduous world tour to generate income. Partly due to bouts of illness and cancellations, the expected financial windfall didn’t materialize; at the end of it, Susy, who alone among the family had returned to Hartford, contracted spinal meningitis and died at 24. Around the same time, Jean was diagnosed with epilepsy and Clara, who desperately wanted to break free from the controlling influence of her parents, found herself pressed into nursing her ailing mother.

Chernow navigates these tumultuous years, which form roughly the latter half of Mark Twain, with aplomb. He gives full voice to Clara’s frustrations — and Jean’s, too: after Livy’s death in 1904, she was shunted off to various sanatoriums in a futile attempt to cure her illness. Quoting from her diaries and correspondence, Chernow sketches a deeply sympathetic portrait of an observant, capable, love-starved young woman who was anything but the helpless invalid her well-meaning but short-sighted parents imagined her to be.

He does well, too, untangling the exasperating web of relationships that marked Twain’s last years, especially those between the author, his live-in official biographer Albert Bigelow Paine, his secretary-cum-housekeeper Isabel Lyon, and manservant (later Lyon’s husband) Robert Ashton. The latter couple’s betrayal of his trusting nature was a late blow, though not nearly so shattering as Jean’s death from an apparent heart attack induced by a seizure on Christmas Eve 1909. Four months later, Twain joined her, Livy, and Susy in the cemetery in Elmira, NY. (Clara lived until 1962.)

Additionally, Chernow delves into Twain’s obsession with prepubescent girls (the so-called “Angelfish”) during the last period of his life. While not offering any diagnoses, neither does he undermine the most likely explanation: that Twain, whose gloom and pessimism were profound, was engaging in a misguided attempt to revive the halcyon days of family life that were, by then, long gone.

Despite the occasionally dark tint of some of Twain’s missives to the Angelfish, Chernow suggests that this was a strange but probably harmless fetish (the children were always chaperoned and no suggestions of impropriety emerged at the time or afterwards). That Clara and Jean resented the girls’ intrusion into their father’s life (and his commensurate neglect of them) is perfectly understandable, which helps explain Clara’s downplaying of Twain’s odd habit in his official biography.

In the midst of all these goings-on, Twain managed to churn out some of the seminal American literature of the late 19th century, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, among them. Chernow discusses each in full and, while one might quibble with his du jour verdicts, that’s par for a Twain biography. Suffice it to say, individual shortcomings in this highly autobiographical fare reflect their author, as do the books’ considerable strengths.

1889 edition of Mark Twain’s A Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.

Chief among the last were Twain’s deep empathy for the downtrodden and his fearlessness speaking truth to power, virtues that emerge in nearly all of his major (and many of his lesser) works. Also notable is Twain’s model of the artist as an engaged social critic. To paraphrase Jonathan Swift, he knew to use the point of his pen, not the feather.

Though he had many blind spots that cost him dearly in his business dealings and personal life, Twain was, throughout his life, remarkably clear-eyed about injustice, abuse, and profligacy in the public sphere. As the United States continues reckoning with the evils of racism, anti-immigrant sentiment, and nativism — not to mention the nauseating spectacle of Christian hypocrisy, Gilded Age-worthy corruption, and creeping authoritarianism — his example continues to resonate.

Though one might wistfully wonder what Twain would have to say about the particulars of our current predicament, the fact is, he wrestled with many of the most pressing issues of our day (or their root causes) in his. Along the way, he found a ready antidote.

“Our race,” he said in his rambling, 500,000-word Autobiography, “has unquestionably one really effective weapon — laughter. Power, money, persuasion, supplication, persecution — these can lift a colossal humbug — push it a little, weaken it a little, century by century; but only laughter can blow it to rags and atoms at a blast. Against the assault of laughter nothing can stand.”

Or, as Twain put it in his notebook in 1888, “irreverence is the champion of liberty and its only sure defense.” Few of any era practiced that art more diligently or brilliantly. However imperfect his subject’s efforts, Chernow’s biography suggests that we’d do well to cultivate a similar brew of knowing impertinence to contend with the demands of our own troubled age.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

A Mark Twain novel that has long fascinated and horrified me – because of its prophetic contradictions – is A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, which serves up some of this writer’s zaniest humor before it embraces his deepest misanthropy. The anti-democratic, anti-technology ending gives us time-traveler Hank and his assistants surviving by setting up electrical fences that slowly but methodically fry all of the England’s knighthood. “Of course, we could not count the dead,” Hank informs us, “because they did not exist as individuals, but merely as homogenous protoplasm, with alloys, of iron and buttons.” There is nowhere for Hank (or Twain) to go after this – he and his helpers are surrounded by dead bodies that are decomposing, with disease soon to come. An anticipatory vision of the Holocaust and Hiroshima that sets the ground for the black comedic narratives of Vonnegut, Butler, etc.

Good God Jonathan. You write brilliant book reviews also???

It appears that Ron Chernow was paid by the word for this overblown book (1174 pages). The author of this book strangely plays down Twain’s (Clemens’) amazing literary achievements considering his lack of formal education and extensive self-taught knowledge. Eccentric, quirky but truly brilliant, Twain continues as one of America’s most beloved national and world cultural giants. At times in this tedious tome, Chernow seems to want to show him as just an ordinary guy with a bit talent which he wasn’t. Twain was so much more that resonates with us today. Considering Chernow’s well rewarded other biographies, I had hoped for much more .

I just finished this massive tome. It was pretty exhausting. I quickly grew tired of the neverending catalogue of personal grievances and business failures. Twain emerged as deeply angry, capricious, and self-centered, and frankly it was off-putting. Similarly, the cataloguing of every medical setback in the Clemens family — particularly the inexorable decline of Jean Clemens from epilepsy — left me nearly as spent as the victim herself.

Perhaps Chernow’s previous biographies of Washington, Grant, and Hamilton got him into a groove. Chernow seems intent on cataloguing every cough, every seizure, every collapse, without full regard of the enervating effect that the narrative would have on the reader. I learned a great deal about Twain the man, but felt I wasn’t really any closer to understanding Twain the writer.