Book Review: “The Hard Work of Hope: A Memoir” — A Guide to Blue Collar Community Organizing

By Bob Katz

On the hard wooden benches of a jail in Lowell, dialoguing with his street-fighting antagonists, we sense the emergence of organizer Michael Ansara’s strategy for working-class political action.

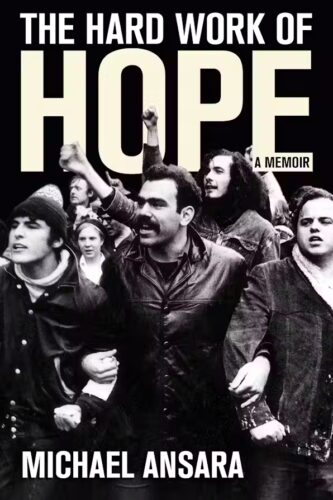

The Hard Work of Hope: A Memoir by Michael Ansara. Cornell University Press, 289 pp.

In the limelight arena of outsized ambitions, some are more interesting than others.

In the limelight arena of outsized ambitions, some are more interesting than others.

“I wanted to become an organizer,” writes Michael Ansara in The Hard Work of Hope, “who could build large organizations that would contest for power, change policies, win structural reforms, and at the same time become great schools of democracy.”

Ansara’s account begins during his high school years in Brookline in the early 1960s. At the age of 15, he was exposed to the righteous passion and welcoming camaraderie of the civil rights movement through a number of familiar Boston figures, such as Mel King, Byron Rushing, and Sarah Ann Shaw, and organizations like CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and SNCC (Southern Nonviolent Coordinating Committee). Ansara turned into a door-knocking, leaflet-distributing, rally-attending, all-in dynamo, arranging buses to the historic 1963 March for Jobs and Freedom and working tirelessly for Noel Day, a Black man running for Congress as an independent against Speaker of the House John McCormack.

“I know what I want to be in life,” he writes. “An organizer.”

By the time 17-year-old Ansara enters Harvard, the Vietnam war is rapidly escalating (Gulf of Tonkin incident) and the Democratic Party’s old guard (Hubert Humphrey) is faltering miserably. Already a savvy veteran of the kind of fiery activism that will soon envelop his campus, his nation, his generation, Ansara is uniquely primed to step up and make things happen.

“I felt it,” he writes. “I felt my generation … could and would re-make America.”

His college years are a whirlwind of nonstop activism. Sure, he downs a beer or two. Enjoys rock music. Has a sweet girlfriend (later to become wife and partner in activism). Seemingly attends classes. But Ansara’s all-consuming focus is ending the Vietnam war (yes, college students then were guilty of such hubris) by way of an involvement with the upstart SDS (Students for a Democratic Society).

If campus activists today had a reason to raise their voices in protest of an inhumane government policy (just saying), there would be much to learn from Ansara’s tactics in rousing an awareness among an initially docile student body (at Harvard as well as many other campuses; the kid was busy) and generating actions designed to mobilize followers, even if those actions displeased university administrators and enraged local police.

Nearly two-thirds of the memoir dwells on these efforts (1964-69), which somewhat surprised me given that Ansara’s post-Vietnam community organizing accomplishments were possibly more exceptional and more relevant to contemporary political challenges.

That said, reading his smoothly written play-by-play detailing how fair Harvard, with Ansara as leading agitator, became a center of fierce resistance as inflamed as Berkeley, Madison, and Columbia had, for me, the feel of watching an ESPN Classic telecast of some legendary Super Bowl from an earlier era (something I tell myself I’m too proud to do). You kind of sort of recall what happened. You probably do recall who won. Still, it’s interesting and maybe revealing to relive it once again.

Port Huron Statement. Teach-in with Norman Mailer and Noam Chomsky. Mass rally on Boston Common. DC rally, Ochs and Baez. South Boston draft board run-in. Participatory democracy. Confrontation with McNamara himself (cool photo in the book of young Ansara beside the reviled Defense Secretary, surrounded by a feisty Harvard crowd). More DC protests. Hayden, Abbie, Oglesby. Writing for Ramparts. Vietnam summer. PL crazies. Murder of Fred Hampton. The Mobe. National Conference for New Politics. Bring the war home!

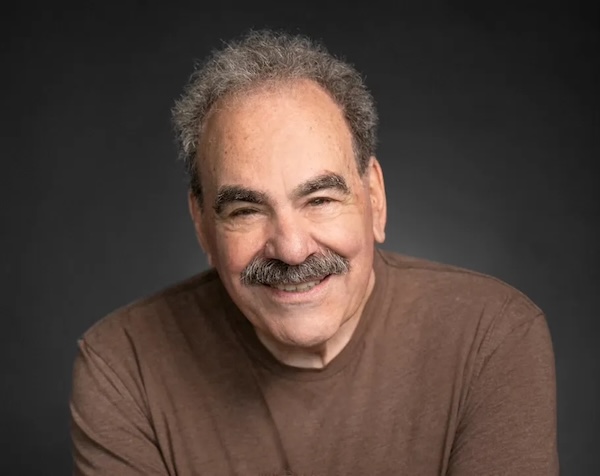

Organizer Michael Ansara. Photo: Liz Linder

One fascinating scene occurs at an antiwar protest in Lowell. Ansara and his wife take refuge in the police station after being attacked and beaten by a gang of riled-up, misinformed youth (to his credit, he does not employ the term “lumpen”) who, by afternoon’s end, come around full circle into tentative alliance after finding themselves attacked by police and jailed. Here, on the hard wooden benches of the Lowell jail, dialoguing with his street-fighting antagonists, we sense the emergence of Ansara’s strategy for working class political action.

What’s next is exactly that, blue collar community organizing, building support for a range of potent lunch bucket issues. Utility rates. Absentee landlords. Food prices. Employment practices. Toxic waste. Plant closings. Unfair taxes. Crooked judges. Redlining.

Fair Share is the organization Ansara creates and directs. He relocates to Dorchester to better integrate, better understand. He summarizes their approach:

Find people who will agree to host a house meeting in their home. Work with them to see who is able to turn out twelve to twenty-five friends and neighbors. After a dozen or more house meetings and several hundred conversations, build an organizing committee, at every point testing to see who can actually lead people. Don’t be fooled by the people who talk the best game. Look for the people who deliver. Don’t lock in leaders too early — leave room at the table for the people who emerge. Offer training sessions in leadership, issues, skills, and strategy. Take several direct actions around the issues that excited the most people. Collect memberships and dues to produce local ownership and financing of the organizing drive.

Fair Share groups spring up across the state in cities and towns of similar need, Chelsea, Lynn, Worcester, Revere, Fall River, Chicopee, New Bedford, Somerville. With over 10,000 dues-paying members, the organization can demand meetings with the Governor and turn out thousands for rallies. They take on Boston Edison, take on Mass Port, take on City Hall. Fair Share is a force. Their press releases make news. Their agenda makes waves. Ansara’s ambition, a virtuous ambition if ever there was one, would seem on the brink of being realized.

At this point in the memoir, I was becoming aware of what felt like dropped hints. A few too many oblique references to his flaws as a leader, his personal failings, and his lack of strategy. Humble is good. But is there something else? On page 246 he writes that, worn out, he departed Fair Share in 1983. On the very next page he tells the reader of a mid-life crisis in 1996 accompanied by a “headline producing scandal.”

No specifics are offered. I did some internet searching. You can do likewise. The man fought many a valuable fight, and if that’s all he wants to say about the matter, well, it’s his book.

Reading Ansara’s memoir, I was struck by its tonal similarity to the popular How I Built This business success genre. In it, a triumphant entrepreneur recounts the long haul of perilous fits and starts that ultimately results in wealth and validation. Ansara’s story, chock full of fits and starts, cannot be so neatly packaged.

Too bad, because the How I Built This genre, replete with useful lessons regarding leadership, team-building, innovation, persistence, etc. really should be repurposed to celebrate quests for the common good like Ansara’s. An increase in cunning entrepreneurs is not what the nation needs in 2025.

Bob Katz is author of six books, including the novel Waiting for Al Gore and the nonfiction Elaine’s Circle. For more: BobKatz.info.