Classical Album Review: The Korngold Symphony — The Great American Symphony?

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Could it be that Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Symphony in F-sharp is the big kahuna of our symphonic music?

What if the Great American Symphony has, in fact, been hiding in plain sight for seventy-three years? What if it was the product of an Austrian-born Jewish refugee from Nazism who achieved unprecedented popular success in Hollywood? In a word: what if it was Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Symphony in F-sharp?

There’s an argument to be made that that’s just the piece.

Korngold was acclaimed a genius early on—by Gustav Mahler, no less—and, while his career saw extraordinary highs, it ended in frustration. His long tenure scoring Hollywood films caused many contemporary critics (and, it seems, more than a few audience members) to dismiss his concert music out of hand. And, as was true for many European Jews, the shadow of Nazism and the Holocaust loomed over his last decades.

The Symphony dates from those years—it was finished in 1952—and is, to outward appearances, conventional. Its four movements are all tonal and it abounds in clear motivic writing of a kind not in vogue in the first decades of the Cold War. The premiere was an under-rehearsed radio broadcast in 1954 and it took nearly twenty more years before the score was heard live.

By that time, Korngold was dead and decidedly out of fashion. Yet the wheels of taste don’t stand still and, eventually, the great man found himself rehabilitated.

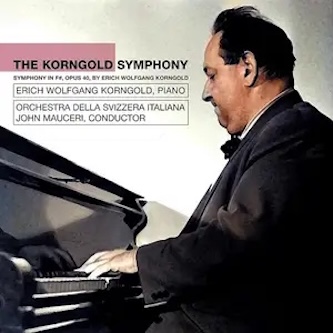

In the meantime, tapes he’d made of parts of a piano reduction of the Symphony emerged and found their way to conductor John Mauceri, whose enthusiasm for music of composers displaced by the rise of Nazism runs wide and deep. Those formed the basis of a recording he made of the piece with the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana in 1997 that has only been released recently on Supertrain Records.

Mauceri’s is an absorbing account, if not quite so polished as André Previn’s near-contemporaneous version with the London Symphony Orchestra for Deutsche Grammophon. Nevertheless, his is a performance that moves with purpose and understanding.

The opening movement’s dramatic architecture is smartly illuminated, as are the Scherzo’s menacing undercurrents. There, the music’s rich dissonances (especially in the Trio) speak clearly. The finale, too, though a shade heavy-footed, has got all the requisite character and cheek.

In between comes a reading of the Adagio that’s a revelation. You could be excused for thinking of this movement as a lament for the whole first half of the 20th century, not just the victims of World War 2 or Franklin D. Roosevelt (to whose memory the larger work is dedicated): from its queasy, Mahlerian opening—the debt Korngold owed to Mahler, which he often disguised very effectively, is impossible to miss—to its moments of spare vulnerability that have some kinship with Shostakovich, this is music of shattering intensity and the urgent, shapely rendition Mauceri and his forces deliver doesn’t stint on extremes. But this fervency and emotional heat doesn’t come at the expense of textural clarity or technical rigor; any way you cut it, this is a mighty and well-recorded performance.

For filler, Supertrain has included those tapes, made in Los Angeles sometime in the early ‘50s, of Korngold playing through his score. Those are fascinating to hear and exceedingly well-preserved; turns out, it’s also touching to hear the composer shouting out the title of each movement from across the decades.

Additionally, there are absorbing liner notes from Leslie Korngold (the composer’s grandson), Supertrain founder Richard Guérin, and Mauceri. The latter recounts playing Rudolf Kempe’s recording of the Symphony for Leonard Bernstein in the late ‘80s and, evidently, Lenny didn’t care for the jaunty finale.

But that section is the work’s linchpin. For all its playfulness, the shadows are never far off. When those threaten near movement’s end, Korngold, in a nifty feat of thematic transformation, repurposes this perpetually gloomy motive into something its opposite, in the process revealing the interconnectedness of these two kinds of music. That’s a specially useful illustration for today: though the burdens of the past are always with us and shape our present, they can be the means for crafting a more productive—and hopefully better—future.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: John Mauceri, Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana