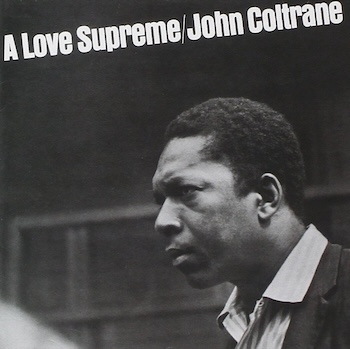

Jazz Commentary: John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” Turns 60 — A Homage

Compiled by Bill Marx

“I believe that men are here to grow themselves into the best good that they can be.” – John Coltrane

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the release of John Coltrane’s magisterial album A Love Supreme, which has meant so much to so many. Some of the magazine’s jazz writers wanted to express what the music meant (and still means) to them. Their reactions are below.

Allen Michie

It was years after I discovered Coltrane’s A Love Supreme that I learned I was listening to part of it all wrong.

It was years after I discovered Coltrane’s A Love Supreme that I learned I was listening to part of it all wrong.

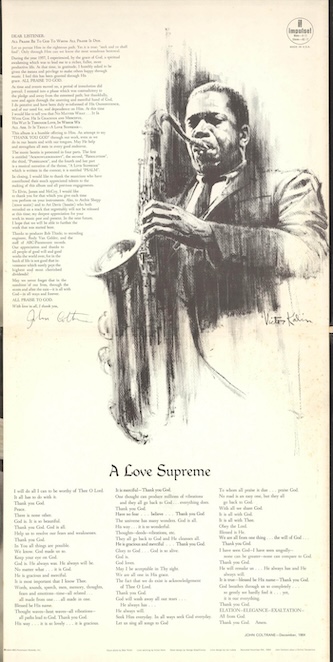

I confess I didn’t look too deeply into Coltrane’s “Dear Listeners” letter and the “A Love Supreme” poem included in the album’s gatefold. I knew the music had an intensely spiritual dimension, but I thought I didn’t need to study the fragmented religious catchphrases in the poetry to have a deeper appreciation of it. The words didn’t strike me as being particularly literary or original.

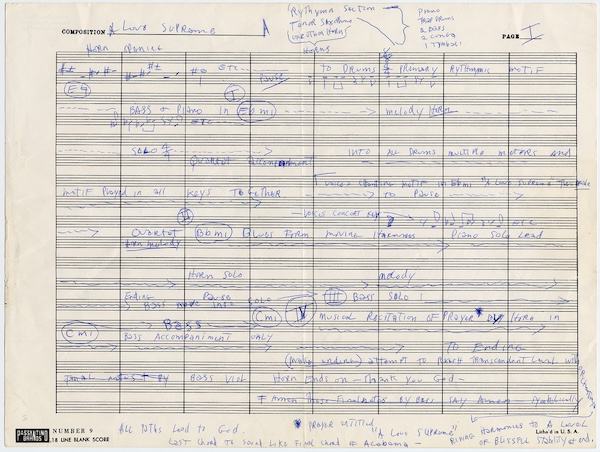

What my eyes skimmed over in Coltrane’s “Dear Listener” letter was the line: “the fourth and last part is a musical narration of the theme, ‘A Love Supreme,’ which is written in the context; it is entitled ‘PSALM.’” My mistake was that I didn’t take this literally.

Coltrane does something in the fourth movement that he had never done before and never did again. I can’t think of another example of it in jazz before that enchanted recording date in December 1964. Coltrane read his poem, syllable by syllable, through his tenor saxophone. You’re supposed to read the poem as you listen to the music. Unlike musicians playing the written melodies to standards, where you can “hear” the familiar lyrics you already know, Coltrane was freely improvising his melodies. He invented and then built his solo around recurring musical motifs structured by recurring phrases in the words, such as “Thank you God.”

It’s not a gimmick. The effect is powerful, and I encourage you to take the time to give it your full attention. For those who sometimes struggle to “get” Coltrane and understand the logic behind what appears to be his chaotic musical approach, this is an excellent place to start.

In order to follow the natural cadences of speech, Coltrane limits the range to the middle of the tenor saxophone to match that of an adult male’s voice. When the voice rises and breaks with emotion, as it does at 2:52 over the lines “Have no fear … believe … thank you God,” you can hear a new level of sincerity of expression, free of cliché or overdramatization. Simple lines like “God is. He always was. He always will be. No matter what … it is God” at 1:14 are expressed as a moment of quiet but uplifting discovery.

As the entire A Love Supreme suite builds to its conclusion, at 5:27, Coltrane’s stately incantation rises to something a human voice would strain to do. It is a disciplined cry, part sorrowful at losing some of our past self, and part ecstatic that a rebirth is underway. “He will remake us … He always has and He always will. It is true — blessed be His name — thank you God.” The music descends to the line “so gently we hardly feel it,” then ascends triumphantly, step by step, through the words “ELATION—ELEGANCE—EXALTATION.”

If you have journeyed with Coltrane this far, the reward is yours as well.

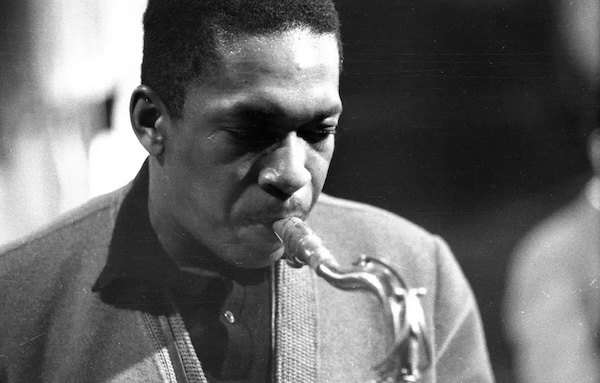

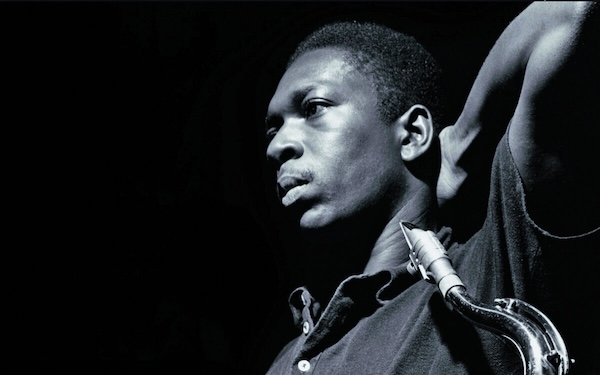

John Coltrane, circa the mid-’60s. Photo: Wikimedia

Steve Elman

John Coltrane had worked the territory before — modality and the blues — but never with such an explicit agenda. What if the music had appeared without its famous title, without the chant of “a love supreme” that surprised so many when they heard it for the first time? But that’s pointless: it is impossible to separate the music of A Love Supreme from its purpose. Coltrane said it was “a humble offering to Him,” and I have always heard it as a seeking, as well — hands and horn uplifted to a nondenominational divine.

“A Love Supreme” is the expression of the first giant step in that musical journey. Coltrane was in good company — the heart of A Love Supreme is like that of Moses on reaching the summit of Mount Horeb; like that of Jesus of Nazareth as John the Baptist was lifting him from the water of the Jordan; like that of Siddhartha Gautama in his final seconds of meditation under the bodhi tree before achieving enlightenment; like that of the prophet Muhammad in the moment the angel Gabriel said, “Recite.”

The search is in Coltrane’s liner notes: “I perceive … His OMNIPOTENCE, and of our need for, and dependence on Him…. In all ways seek God everyday…. No road is an easy one, but they all go back to God…. I have seen God. I have seen ungodly…. He will remake us …”

Coltrane revisited A Love Supreme in live performance (notably with Carlos Ward and Pharoah Sanders added as solo voices, in Seattle in October 1965). The original themes and improvisations have been reexamined and reinterpreted by Branford Marsalis’s quartet, by Wynton Marsalis in a large-ensemble version for the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, by violinist David Balakrishnan for the Turtle Island String Quartet, and by Jeff Scott in his “Passion for Bach and Coltrane” (Fuse review), along with others of much less renown, like the sacred steel group the Campbell Brothers, Catalan drummer Vicente Espí, Hungarian guitarist Juhász Gábor, and the big band led by French composer Christophe Dalsasso and saxophonist Lionel Belmondo.

Individual movements of the suite have inspired reimaginings by (among many others) saxophonists Kenny Garrett, Eric Alexander, and Lakecia Benjamin; Alice Coltrane, with Frank Lowe, Leroy Jenkins, Reggie Workman, and Ben Riley; singer Kurt Elling, in a vocalise version setting philosophical words to Coltrane’s solo on “Resolution”; guitarists Carlos Santana and John McLaughlin; keyboardist-producer Robert Glasper; and Canadian pianist Andy Milne, in a symphony arrangement for Carlos Simon’s Coltrane: Legacy for Orchestra (Fuse review).

Even though the reinterpretations vary widely in sound and quality, they all share an astonishing continuity of reverence for the original, as if A Love Supreme were a cathedral, striking its visitors into awe and contemplation.

In all his music, consciously and unconsciously, Coltrane sought to fill the emptiness of a hollow world. The yearning of A Love Supreme touched something universal, and the musical expression of that yearning touched the souls of millions. Its power will not be diminished by time.

Handwritten sheet music for John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. Photo: Wikimedia

Stephen Provizer

Other Arts Fuse writers will no doubt discuss the creation of A Love Supreme and place it in a broader jazz context. My contribution is a personal story, inspired by the only slight exaggeration that this album saved my life. Twice.

My sister Marlene gave me the album for my 15th birthday, the year it was released, 1965. She had no idea at the time, but days before, the girl I loved had told me she no longer wanted anything to do with me. I was devastated and took to my bed, crawling out only for an occasional meal. When Marlene brought me the LP, I could only muster a pro forma thank you.

My family’s record player was a console that sat in the dining room — a Sylvania. At that point, I had heard Coltrane’s Live at the Village Vanguard, so I knew he was going in new directions, but I was not prepared for what I heard. I put the record on and lay under the dining room table to listen. I was more than confused by what I heard. In fact, my breathing momentarily stopped. By the time the record was over, my spirits had lifted and I knew I would never hear or play music the same way again. Life seemed not so dire and perhaps, I thought, love might find me again.

My obsession with Coltrane was such that when I went to college, I finagled a grant to study his life. At 19 years old, and wearing a fedora in an attempt to look older, I hit the road to North Carolina, Philadelphia, and New York City; I interviewed as many of the people who knew him as I could. Some of this material was published, but I didn’t write a biography because Alice Coltrane’s lawyers wouldn’t let her speak to me unless I had a publisher, and I couldn’t get a publisher until…

To frame the second life-saving incident, I will remind people that this was the era of the Vietnam War. In 1969, the Selective Service lottery was held and my number was 132. I was clearly going to be drafted — I was not interested in going to war. I was called for my physical. I didn’t quite manage to get under the minimum weight for my height, although carrying my trumpet and devising some interesting sexual inclinations did compel the shrink to write on my form that I had “overt character disorders.” I knew I needed to apply for conscientious objector (C.O.) status. And this is where A Love Supreme reappears.

You have to submit a written statement to your draft board that establishes your religious and/or ethical claim to be a conscientious objector. I am Jewish and was bar-mitzvah, but my claim was not based on that. Instead, I included a copy of the liner notes of A Love Supreme and explained that this was the basis of my spiritual beliefs. When I went to my draft board in Brookline’s Coolidge Corner, I brought a man with me — a well-known town guy who umpired softball games. He testified to my sincerity and helped to ground my esoteric claims. I explained the basis of my application to the board: I was granted C.O. status and then declared 4-F. Thank you, John Coltrane. Because of you and A Love Supreme, I never had to see the jungles of Southeast Asia.

Steve Feeney

I had an early introduction to the music of John Coltrane by way of a gift from a friend — a double vinyl album that included two Miles Davis releases: Workin’ and Steamin’ from the 1950s. Wow, that tenor sax player in the group had a powerful, distinctive sound. But it was my later introduction to Coltrane’s own A Love Supreme that really opened my ears, which at the time were otherwise accustomed to a diet of psychedelic jams.

As we listened to the disc, a member of my group of young friends nearly threw me off by insisting on singing along in a peculiar way to the spiritual chant at the start of the album. She insisted on changing “A Love Supreme, A Love Supreme” to “I Love Ice Cream, I Love Ice Cream.” The memory of that somewhat amusing, but nonetheless supremely annoying, irreverence still freezes my brain for a moment when I play the album.

In any event, I was, and remain, more focused on the instrumental music that followed the chanting. “Pursuance” is the section (or movement) in the four-part work that still blows me away. It contains the most intense jazz quartet music I have ever heard. I use the qualifier “jazz,” but really, it holds up against any serious quartet music.

The mix of joy, humility, and African American roots in A Love Supreme makes for a triumphant recording, a testament to the chemistry of the leader, pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones. I think I’ll stick the disc in the CD player (I still have one) in my car and head for a visit to the outer reaches of this great music — maybe taking some time out for a quick stop somewhere for a cone.

Michael Ullman

In January of 1965, Impulse Records issued John Coltrane’s quartet record, A Love Supreme. I bought my copy soon after. I was already an engaged teenage Coltrane fan. I had heard Trane with Miles Davis and also on the Coltrane records I had already acquired — among them, Coltrane Plays the Blues, My Favorite Things, and the more recent Crescent. But my response, and that of others, to A Love Supreme was nonetheless different from our reactions to previous Coltrane performances, and perhaps from any previous jazz record. I remember, in the fall of 1967, walking across the green at the University of Chicago and crossing paths with a young man who was chanting, “a love supreme, a love supreme.” Abruptly, it seemed my semiprivate obsession with middle and late Coltrane was now widely shared, at least among hip Ivy League types.

A Love Supreme changed the public’s perspective on Coltrane. From 1965 on, his image was surrounded by an air of piety, especially following his premature death in 1967. After Trane, some jazz was increasingly seen as an expression of a spiritual force. No one then was surprised when Pharoah Sanders issued records like Karma and Wisdom Through Music, or when he chanted, “The Creator Has a Master Plan.” Alice Coltrane continued in Trane’s path with records like Lord of Lords. On the other hand, people were startled when they saw a photo of Coltrane smiling: he was typically seen as sober as an old-fashioned judge. His music reflected his seriousness. With its long, almost placid lines and out-of-tempo feel, the introduction to the title cut of Crescent may have been a musical precursor to A Love Supreme. But the latter album came with a poem, and the piece was made up of four movements — “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm.” This setup suggested the path of an effortful but ultimately successful spiritual awakening. Listeners believed that his music offered them a healing journey, an escape from a war-torn political scene and an increasingly agitated racial climate.

John Coltrane. Photo: Wikimedia

In his notes, Coltrane wrote about his own journey: “During the year 1957 I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, more productive life.” He backslid temporarily, he said, but had come back to his chosen path. A Love Supreme was his way of saying thank you and also suggesting a way for the rest of us to follow. The way wasn’t meant to be tedious: he ends his poem by telling us what God had vouchsafed him: “ELATION—ELEGANCE—EXALTATION.” “Acknowledgement” begins with a splash on Elvin Jones’s gong and a fanfare from Coltrane, who withdraws as McCoy Tyner fills in and then seems to dwindle away in anticipation. The introduction ends with Jimmy Garrison’s repetitions of the four-note theme that A Love Supreme will always be known for. Coltrane returns, interjecting the straightforward force of his playing as he moves from overblown high notes to the depth of his tenor. He plays short phrases that seem to move with their own harmonic logic. At his most intense, he travels higher in his horn, swirling around an imagined center. Eventually, of course, he chants “a love supreme.”

After one acknowledges the omnipresence of God, there is “Resolution,” which precedes the action suggested by the following movement, “Pursuance.” The theme of “Resolution” is just as attractive as its predecessor. Here, though, McCoy Tyner solos at length with his own pounding, two-handed force: he plays a whole chorus of thumping chords. Jones is given the opportunity to open “Pursuance.” Coltrane ensures that every quartet member gets his feature time — still, the saxophonist dominates with his sometimes shrieking intensity. The concluding movement, “Psalm,” is a proclamation, perhaps of well-earned serenity. A Love Supreme has been treated by critics as Coltrane’s signature album. I don’t think he thought of it that way, as if its significance were set in stone. The next day, he rerecorded several movements, and in his next session he recorded “Chim Chim Cheree” from Mary Poppins. His ears remained open and his musical spirit playful.

A wonderful group of impressions and recollections. Allen Michie — How did you discover the role of the poetry in the music? I seem to remember that as a revelation by a critic who was digging into the process of Coltrane’s composition and its recording long after the fact.

Lewis Porter has done a lot of work on that.

As I recall, I learned it from the essay by Ravi Coltrane in the booklet for the 2002 reissue.

“Psalm” is not the first time Coltrane played his poetry through his horn. In 1965 Coltrane told Michel Delorme that “Psalm” “is the longest I’ve ever written, but certain pieces from the album Crescent are also poems, like ‘Wise One,’ ‘Lonnie’s Lament,’ ‘The Drum Thing.’ Sometimes I do it this way because it’s a good approach to musical composition.” [Jazz Hot, Sept. 1965]

A contemporary review of A Love Supreme by Doug Pringle explicitly stated that Coltrane was playing the poem on “Psalm”: “Psalm is what Coltrane calls ‘a musical narration of the theme’; he sets to music the text in the liner, phrase-by-phrase, in the manner of liturgical plainsong. The true power of his performance can only be felt by following the text with the music.”[Coda, Oct./Nov. 1965]

–Chris DeVito

‘A Love Supreme 50 Years on’ …. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b051s0fp