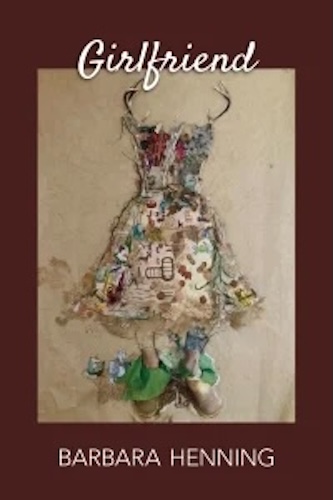

Poetry Review: Ode to Sisterhood — Barbara Henning’s “Girlfriend”

By Michael Londra

Chronicling acts of feminist sisterhood, Girlfriend memorializes a mutual support system that has been among the backbones of American life.

Girlfriend by Barbara Henning, Hanging Loose Press, 94 pp, $18.

Wallace Stevens once declared that a poet is “the priest of the invisible.” A conservative Republican, Stevens saw this role as a defense of elitist aesthetics. His aristocratic approach to writing verse privileged abstract metaphysics over any appeal to writing for the hoi polloi or leftist politics. Reject Stevens’ patrician leanings and his sentiment can be reinterpreted today to embrace a wider sense of how a poet does justice to the “invisible.” For one, poets are guardians of language, charged with the retrieval of discarded truths. Poets amplify voices that have been rejected or ignored by society’s mainstream. Poetry reveals what is unseen in our limited vision of the world. Like Newton discovering gravity, poetry reveals what is unseen.

Barbara Henning’s new poetry collection, Girlfriend, exemplifies these duties of expanding our limited version of the world. Originally from Detroit, she moved to New York City in 1982. Henning, now 76, has authored eight books of poetry and four novels, spending the majority of her time living in bohemian communities, cultivating close relationships with a variety of nonconformists. Earning a PhD along the way, Henning has lived “All for beauty, truth, and love, big love,” at least that is how she encapsulates it in the lyric “Diane.” In the acknowledgements to Girlfriend she explains that the book is structured as a “meditation on my friendships with girls and women…adult friends…but also mentors and authors who were important during turning points in my life.”

The volume is a sequence of over sixty prose poems and they read like a surreal road trip crisscrossing the last seven decades of American culture. Each poem is compressed into a meticulously constructed paragraph of very few sentences, labeled with someone’s first name, and paired with an accompanying photo. We can see exactly who Henning is writing about—family members, yoga teachers, professional colleagues, fellow mothers, critics, activists, and her daughter’s first babysitter, among others. A hybrid work of images and text, Girlfriend foregrounds a wide range of issues—race, gender, and class. The cultural/political contrast with what is happening today highlights what we are losing. At the moment, immigrants are being ‘disappeared’ off of American streets, the federal government is purging people of color from online platforms, and LGBTQ+ protections are being rolled back by the Supreme Court. Henning eulogizes a striking alternative: a vanishing mid century ‘golden age’ of accessible higher education, upward mobility, and social change.

This is not to say that Girlfriend is nostalgic or sentimental. This is partly because Henning is deeply personal. Her choice of not pluralizing her title, for example, reinforces her belief that the universal is inevitably singular. As Henning puts it: “A little thing can become a big thing. Even if we aren’t aware of it” (“Faye”). Journeying from childhood experiences in drive-ins to Ocean Parkway bike rides in Brooklyn and hanging out at the Nuyorican Poets Café on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Henning chronicles her adventures in artistic growth and collaboration, evoking the thrill of discovering previously unknown writers, such as the critic Mikhail Bakhtin and the French experimentalists Oulipo. In these pages, the personal is ever present: there are divorces, deaths, and harrowing near-death experiences. Henning’s life is spared, for example, when an intervention diverts a speedboat from plowing into her: “He might have run me over, except in the nick of time, you tapped him on the shoulder” (“Marlene”).

Henning is adept at showing how we hem ourselves in because of fear and then struggle with the consequences. “Lucy” details Henning’s burgeoning friendship with an African American co-worker. The sense of regret at her decision is palpable: “After I inherited my grandfather’s old Dodge, sometimes I’d drop you off at home. I remember how you would slide down low in the seat so no one could see you as we drove…[w]e once imagined going on a trip together, down south where you had relatives, but this was ’69 not long after Martin Luther King was assassinated, and we were afraid to drive out of the city in the same car together, but I remember we imagined it and then decided not to.”

Chronicling acts of feminist sisterhood, Girlfriend memorializes a mutual support system that has been among the backbones of American life: “When you were in the hospital for a surgery, I helped you shower and wash your hair” (“Georgia”). Henning on her daughter-in-law’s suicide: “A few years later, when she took her life, you were there for my son…[f]rom one mother to another, Namaste” (“Nancy”). Other expressions of gratitude: “Will I help your daughter with her essays? Yes, of course, anytime” (“Cari”): “When I became pregnant, you said you’d help with the birth…you caught the baby and helped the placenta release” (“Kathy”).

Poet Barbara Henning. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Girlfriend offers a smorgasbord of reflections. Riffing on fictional characters from well-known works of literature, Henning clearly enjoys the serious fun behind “Louisa,” dedicated to writer Louisa May Alcott, of Little Women fame: “Jo March, my favorite character of yours, was boyish and independent, a lot like you.” In “Catherine,” she meditates on the Brӧnte siblings by way of the female protagonist of Wuthering Heights. It is also another way to ruminate on family loyalty—one of the signal motifs marbling Girlfriend: “As a young girl, I used to dream about you and the Moors…[l]ike me, your mother died early in life.” The Brӧntes, Henning tells us, “barely lived past thirty, but they relied on each other…for their survival.” “Ginny” brings this sentiment back home: “As children, all four of us took care of each other; and even if our lives are very different now, we are still there for each other.” Tributes to Margurite Duras and Virginia Woolf (whom Henning dresses up as in grad school; photographic evidence included), join a few curveball selections, such as thoughts on the rarely-ever discussed poets Mina Loy and H.D.

Most importantly, Girlfriend does not flinch from calling out misogyny. She looks with hard-eyed sympathy at the relationship between Objectivist poets Lorine Niedecker and Louis Zukofsky. Henning never met Niedecker, but she “felt protective of you and upset with him…for insisting you throw out all letters revealing your personal relationship, a decade of correspondence…[a]nd he insisted you have an abortion when you didn’t want one, even though you were willing to raise the child on your own” (“Lorine”). In addition to toxic sexism, male violence against women is chillingly depicted: “When I asked him to leave, he refused. He held me down with his hand on my throat and I lay there as still as possible. Afterwards, I pretended everything was normal. Did he want something to eat?” Talking in the poem to her former roommate girlfriend, who was away when the attack occurred, Henning is ambiguous about what followed: “I didn’t tell you about him. I didn’t tell anyone…I don’t know where you are now…I moved on. We all moved on” (“Suzie”).

Throughout, yoga stands as respite, a ready source of renewal: “When I started practicing yoga, the breath work and movement pulled my mind back into my body” (“Julia”). Poetry is “breath work” as well. (Paul Celan called it “breathturn.”) Breathing, for a poet, might be the key to self-realization: “I was lucky to be a writer and reader, and eventually I was lucky to learn how to breathe with my body and mind, in my own room, in rooms with others” (“Jean”).

The final poem in Girlfriend, “Linnée,” is a love letter to her child. It testifies to the power of women’s generational solidarity because the term “girlfriend” contains a wealth of different meanings. After all, in the struggle for equality and recognition, mothers and daughters are sisters. And, despite setbacks, they, and we, must refuse despair: “No matter the difficulties and losses in life, it is all so stunningly beautiful, isn’t it?”

Michael Londra’s Arts Fuse review Life in a State of Sparkle—The Writings of David Shapiro was selected for the Best American Poetry blog. His fiction, poetry, and reviews have appeared or soon will in DarkWinter Literary Magazine, Restless Messengers, Asian Review of Books, The Fortnightly Review, Boog City, The Blue Mountain Review, and Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, among others. He contributed the introduction and six essays to New Studies in Delmore Schwartz, coming next year from MadHat Press; and authored the forthcoming Delmore&Lou: A Novel of Delmore Schwartz and Lou Reed. He lives in Manhattan.