Classical Album Reviews: “Ravel Fragments” & Stephen Hough plays Hough

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Pianist Bertrand Chamayou demonstrates just how mercurial and influential Ravel could be; composer-pianist Stephen Hough’s Piano Concerto casts a Ravel-like spell.

Pianist Bertrand Chamayou demonstrates just how mercurial and influential Ravel could be; composer-pianist Stephen Hough’s Piano Concerto casts a Ravel-like spell.

One of the banes of the classical music world is its obsession with anniversaries, especially when it comes to major composers. Sometimes, however, surprises ensue. This year in France, for instance, the state is focusing not on marking the 150th birthday of Maurice Ravel but, instead, on the centenary of the iconoclast Pierre Boulez.

Given how heavily that country’s government invested in Boulez’s work during his long lifetime, such a tack is maybe not so surprising. Equally predictable, though, is the fact that most record labels haven’t followed suit: Boulez’s highly abstracted, hyper-cerebral style has always been a tough sell. Instead, the market has been saturated with yet more doses of Ravel — some middling, some good, some superb.

Ironically, Boulez—who could be a marvelous Ravel conductor—doesn’t make an appearance on one of the latter, Bertrand Chamayou’s Ravel Fragments. Instead, several of his contemporaries, like Salvatore Sciarrino and Betsy Jolas, do, and, in the process, demonstrate just how mercurial and influential this 20th-century classicist actually was.

By far, the album’s most striking inclusion is Sciarrino’s De la nuit, a sort of hallucinogenic mashup of Ravel’s “Ondine” and “Noctuelles.” Chamayou’s performance is extraordinarily controlled, his command of the notes almost superhuman. Though the reading’s dynamic range feels a shade constrained, the music’s freewheeling play of color and gesture is enchanting.

Jolas’ Signets is likewise intense, though more pungently dissonant. Another echo of Gaspard de la nuit crops up in Frédéric Durieux’s Pour tous ceux qui tombent, its “Le Gibet-like” moments of eerie stasis interrupted by unexpected flashes of violence.

Meantime, Joaquín Nin’s Mensaje a Ravel offers spades of slinky playfulness while Ricardo Viñes’ Menuet spectral (à la mémoire de Maurice Ravel) stands as a smoky, nostalgic counterpart to Ravel’s own various forays into that genre. A commemorative vibe marks further selections by Alexandre Tansman (Prélude No. 5), Xavier Montsalvatge (Elegía a Maurice Ravel), and Arthur Honegger (“Hommage à Ravel”).

The man of the hour, himself, is also represented—just not, perhaps, as you’d expect. Instead of assaying Ravel’s original piano music (Chamayou committed that to disc about a decade ago), the pianist offers six arrangements of the composer’s work.

Three of them—“Trois beaux oiseaux,” “Chanson de la mariée,” and Pièce en forme de habanera—are his own handiwork and smartly beguiling. In the composer’s own adaptation of La Valse, Chamayou brings a lilting fluency to a performance that’s fully alive to the music’s turbulent spirit, yet never derailed by its many sprays of color, character, and filigree.

The “Fragments symphoniques de Daphnis et Chloé” is a welcome find: rich, sinuous, and well-directed. So are Ravel’s arrangements of that ballet’s “Danse légère” and “Scène,” both of which shimmer sumptuously.

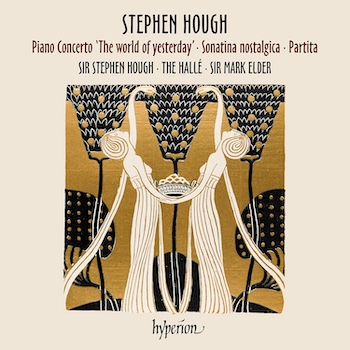

The spirit of Ravel is not far removed from the music of Stephen Hough, either. His Piano Concerto, which gets its debut recording courtesy of the composer-pianist, the Hallé Orchestra, and Sir Mark Elder, might possibly be described as a two-handed British response to the French icon’s Concerto for the Left Hand.

The spirit of Ravel is not far removed from the music of Stephen Hough, either. His Piano Concerto, which gets its debut recording courtesy of the composer-pianist, the Hallé Orchestra, and Sir Mark Elder, might possibly be described as a two-handed British response to the French icon’s Concerto for the Left Hand.

That’s not a bad thing, and the main points of comparison are structural, not thematic. There’s a spacious, dreamy opening; a big, bold cadenza; and then some lively dance music to round things out. Everything unfolds in a concise, uninterrupted twenty minutes.

If Hough isn’t reinventing the genre here, neither does he need to: this is music that fits into a niche all its own. The composer’s ear for crafting memorable tunes is commendable; not for nothing is the second movement (“Waltz variations”) perfectly charming. What’s more, his pianism is exceptional and his ear for instrumentation wonderfully alert. The end result is music at once spunky, playful, and appealing—but also substantive. Hough, Elder, and the Hallé play it to the hilt.

This short disc’s filler (timings come in under forty minutes) consists of two brief solo works, the Sonatina nostalgica and Partita. The deceptive simplicity of the former culminates in an unexpectedly fervent “A Gathering at the Cross” while the latter’s alternations of honey and vinegar sometimes call to mind the aura and textures of more Ravel—this time, Le Tombeau de Couperin.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Bertrand Chamayou, Erato, Hyperion, Hyperion Records, Maurice Ravel, Pierre Boulez