Book Review: “The War of Art” — Waging Creative Defiance

By Lauren Kaufmann

The book provides ample proof that activist artists, when determined, can use their work to influence our thinking in positive ways, and effect change.

The War of Art: A History of Artists’ Protest in America by Lauren O’Neill-Butler. Verso Books, 240 pages. $29.95

As we witness, and participate in, protests against the current administration, we see the power of political activism. For many years, American artists have deployed creative campaigns to capture public attention and affect public policy. Lauren O’Neill-Butler’s new book, The War of Art: A History of Artists’ Protest in America, traces the history of some of the movements that have drawn attention to problems that have plagued modern society —the AIDS crisis; the fight for women’s rights; injustice toward Indigenous people, the LGBTQ+ community, and prisoners; and unfair representation of women and minority groups in museums.

As we witness, and participate in, protests against the current administration, we see the power of political activism. For many years, American artists have deployed creative campaigns to capture public attention and affect public policy. Lauren O’Neill-Butler’s new book, The War of Art: A History of Artists’ Protest in America, traces the history of some of the movements that have drawn attention to problems that have plagued modern society —the AIDS crisis; the fight for women’s rights; injustice toward Indigenous people, the LGBTQ+ community, and prisoners; and unfair representation of women and minority groups in museums.

O’Neill-Butler’s book covers a roughly 50-year span, beginning in the late ’60s. She spotlights some of the artists who have focused their attention on social injustice. Her examples show that, despite lacking money and political influence, artists who are sufficiently savvy and persistent can be highly effective, although their gains may be temporary and their progress may chart an uneven path.

Because artists possess the skills and creativity to present visual statements that pack a punch, they can reach people with persuasive intensity. The book posits that whether they create posters, organize sit-ins, instigate writing campaigns, or produce 3-dimensional environmental statements, activist artists have raised awareness, promoted improvements, and brought about change in the culture.

The book starts out by addressing artists’ confrontation of the AIDS crisis of the ’80s. O’Neill-Butler recounts the story of artist David Wojnarowicz, who had been diagnosed with AIDS in 1987 and broadcast a message on his jean jacket. Over a painted pink triangle, he used white paint to write: “IF I DIE OF AIDS—FORGET BURIAL—JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE FDA.” Wojnarowicz wore the jacket while demonstrating at the Food and Drug Administration in DC. A year earlier, he had lost his friend/mentor/lover to AIDS.

It’s important to remember that, in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, the Reagan administration blamed victims for contracting HIV, attributing it to their moral weakness. The FDA had not devoted scientific research to understanding AIDS — its cause or potential treatment — despite the fact that more than 47,000 Americans had died of AIDS by 1987. In October 1988, a large crowd of protesters descended on FDA headquarters in Rockville, Maryland, to stage what they called a “Seize Control of the FDA” protest. Wojnarowicz’s jacket played an important role and, in the year after the protest, the FDA and the National Institutes of Health allocated funds to AIDS research.

In the same chapter, O’Neill-Butler draws a parallel between the FDA’s inaction on AIDS and the CDC’s slow response to gun violence. She notes that some protesters of school shootings have adapted Wojnarowicz’s slogan; the book includes a photo of a protest sign from 2018 that reads: “If I die in a school shooting — forget burial. Drop my body on the steps of the Capitol.” In a discussion of violence against transgender individuals, she writes about states that have passed legislation curtailing transgender rights and supplies a photo of a protester wearing a jean jacket with the words: “If transphobia kills me, forget burial. Drop my body on the steps of Congress.”

O’Neill-Butler examines the efforts of women artists to gain traction in museum representation. WAR, Women Artists in Revolution, comprised artists who focused on gaining recognition of their talents. Working from 1969 until 1971, WAR dedicated its efforts to persuading major institutions to increase their acquisitions and exhibitions of women’s artwork. They also pressured museums to collect and display the work of Black artists.

In 1969, several members of WAR met with John Szarkowski, director of MoMA’s photography department, and Betsy Jones, a curator of paintings and sculpture. The outcome of their meeting was positive; afterwards, Szarkowski and Jones decided that they should “make an organized and extra effort to search out the work of quality by women artists,” and that “an exhibition of women’s art be given serious consideration.”

The group also pressed for better representation at the Whitney Museum. Reassurances were given to the press that the museum was going to provide women artists with greater exposure. Still, in the 1969 Annual exhibition, there were 143 artists represented, and only eight were women. Frustrated by the lack of commitment from the institution, members of WAR went on a letter-writing and phone-calling campaign, urging curators to increase their holdings of artwork by women. Stephen E. Weil, the museum’s administrator, retorted that he would not meet with the group to talk about quotas at the Annual exhibition.

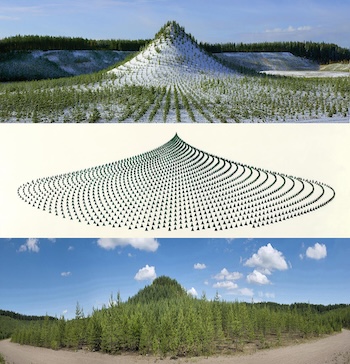

Tree Mountain – A Living Time Capsule – 11,000 Trees, 11,000 People, 400 Years (Triptych) 1992-1996, 1992/2013. Photo: courtesy of Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects

Members of WAR struck back by creating an attention-grabbing campaign. Women dropped eggs, sometimes hard-boiled, sometimes not, throughout the museum. They started picketing outside the museum every weekend. In the fall of 1970, the group composed a fake press release, sent on museum letterhead, that stated that half of the artists in an upcoming exhibition at the Whitney were women. Feminist critic and scholar Lucy Lippard participated in this effort, and it proved to be effective. Several curators announced that 20 percent of the artwork in an upcoming show would be made by women. Although WAR desired 50 percent representation, the progress, though disappointing, was, nonetheless, a step in the right direction.

O’Neill-Butler explores the efforts of an organization called the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), aimed at increasing representation of Black artists in museums. The group met with officials at the Whitney for six months, but talks broke down after the museum refused to hire a Black curator for an exhibition called “Contemporary Black Artists in America.”

The group pivoted and focused its efforts on developing arts programs in prisons. After the infamous uprising at the Attica Prison in 1971, BECC leaders appealed to then Governor Nelson Rockefeller. They made a compelling case for a culturally oriented rehabilitation program. After winning approval for the idea, BECC embarked on creating the Prison Cultural Exchange Program, which endured until 1982. Prisoners at federal and state facilities took workshops in art, writing, theater, and performance. By 1989, there were about 40 programs in 20 states. Benny Andrews, one of the founders of BECC, encouraged prisoners to continue their education after their release. In 1982, in a move reminiscent of what we’re seeing now, the Reagan administration directed the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) to halt its support of the prison programs. The demise of the BECC was a direct result of the cessation of funding from the NEA.

Born in 1931, and still going strong, Agnes Denes has used her art to call for social and ecological justice. In the late ’60s, she began to create works that are now considered early milestones in the Land Art movement. In 1972 she co-founded A.I.R. Gallery in New York City, a women’s art gallery. Over the years she has gained tremendous respect in the art world for visionary works that express concern for the environment. In 1982’s Wheat Field—A Confrontation Denes planted a field of red spring wheat in two acres of rubble in the Battery Park Landfill in Lower Manhattan. For Tree Mountain, begun in 1992, Denes invited 11,000 volunteers to plant pine trees in a small town in Finland. The project was envisioned as a way to restore the land: the site is legally protected against deforestation for the next 400 years.

The book honors the passion and integrity of artists who identify a problem and conceive of creative ways to protest. It demonstrates that activist artists, when determined, can use their work to influence our thinking in positive ways, and effect change.

Lauren Kaufmann has worked in the museum field for the past 14 years and has curated a number of exhibitions. She served as guest curator for Moving Water: From Ancient Innovations to Modern Challenges, currently on view at the Metropolitan Waterworks Museum in Boston.

Tagged: "The War of Art: A History of Artists’ Protest in America"