Book Review: “Room on the Sea” — Low Tide

By David Mehegan

Room on the Sea is impressively crafted and written, but its lack of bite, drive, and action left me restless.

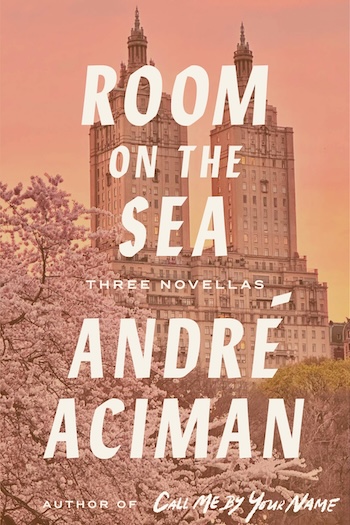

Room on the Sea by André Aciman. Farrar Straus & Giroux. 264 pp. Cloth. $27.

To have one’s novel made into a movie that wins an Academy Award, as happened in 2017 with André Aciman’s 2007 novel, Call Me by Your Name, is surely an authorial thrill (all the more when the author gets a bit part, as Aciman did). But there are costs as well. A film is a translation. When asked what he thought of the 1987 film version of The Witches of Eastwick, John Updike said with ambiguous courtesy, “I recommend the book.”

To have one’s novel made into a movie that wins an Academy Award, as happened in 2017 with André Aciman’s 2007 novel, Call Me by Your Name, is surely an authorial thrill (all the more when the author gets a bit part, as Aciman did). But there are costs as well. A film is a translation. When asked what he thought of the 1987 film version of The Witches of Eastwick, John Updike said with ambiguous courtesy, “I recommend the book.”

But the film made Aciman famous – not at the level of its leading man, Timothée Chalamet, of course (Aciman will never be courtside at a Knicks game), but in the quantum-level of letters. He returns now with a very different book, Room on the Sea, three novellas. Each features in its way the extended aesthetic, intellectual, and internal verbal mastication found in Call Me by Your Name.

In “The Gentleman from Peru,” eight young Americans on a Mediterranean sailing trip are delayed in an Italian seaside town while their boat’s engine is repaired. Dawdling in a hotel dining room, they speculate about the solitary gentleman at a nearby table, of late middle or early old age, white-bearded and diminutive in a navy-blue jacket, smoking an occasional cigarette. Suddenly he stands and heads straight for Mark (no one in the story gets a last name), who is suffering shoulder pain from a recent injury. He puts his hand on Mark’s shoulder, counts to five, and the pain miraculously disappears.

From this and subsequent incidents we learn that Raul (who speaks “flawless Oxonian English” with a faint Hispanic accent) is a miracle worker gifted with supernatural knowledge of past and future, including that of particular lives. He presses Basil to warn Malcolm, a friend in New York, to scrap an impending financial deal. Basil is skeptical but complies and, of course, the warning proves prescient and Malcolm averts a disaster. The Americans are surprised by Raul’s powers, but accept them readily, as though he were a gifted prestidigitator who says, “pick a card, any card” and tells you which you picked.

This is the setup for Raul’s interest in Margot, an acerbic member of the group. Away from the others, he reveals details of her past which are known to her, but other information that is unknown and more disturbing, redolent of a tragic history, even reaching the point of suggesting transcendence of time and transmigration of personality. Who is Raul and who is Margo? How does he know her? At one point he says, “Your name is Marya.” Like the others, Margot/Marya has a remarkably relaxed reaction to all this. She never says or thinks, “This is baloney. This guy gives me the creeps.”

There is a startling revelation but no shattering conclusion to this 100-page story (Aciman doesn’t do shattering). Raul’s musings about mismatched generations, loves and connection, including a bit about a grave, which manifest as a bit sentimental, even a little gothic, command the ending. It appears that the otherworldly is what interests the narrator, not so much the human players. The Americans are thinly drawn. The spooky gentleman from Peru is the closest thing to a realized character; at least he knows what he wants.

Paul and Catherine, married but not to one another and apparently about the same age as the Peruvian miracle-worker, meet in a lower Manhattan jury pool, thrown together over five days while awaiting trial assignments. This situation in “Room on the Sea,” from which the book takes its title, is a clear recipe for incipient romance. That of course is what happens, but unlike the carnality in Call Me by Your Name, theirs is a decidedly cerebral and loquacious encounter.

He is a successful white-shoe lawyer, semiretired, and she is a psychotherapist. She calls herself “basically a headshrinker.” (Do therapists really use this word for themselves?) After a day in the jury pool, she “takes the Eighth Avenue to the Upper Shrink Side” while Paul walks to his Pearl Street office. Over coffee or lunches during breaks, or sitting together waiting to be called, they reveal to us and one another that their long marriages are unsatisfying (we hear about, but don’t see, tiresome Claire and Jonathan) and that the person they’ve just met is far more appealing in every way.

They circle round and round their attraction and eventually plan and carry off a weekend together (the spouses are either indifferent or naively unsuspicious) at a beach place in East Hampton long owned by Paul’s family and, while they do get to bed, it is only mentioned in passing after the fact. These two are drawn to one another but without detectable passion. Oh well, they’re grandparents. They seem to be have agreed to a permanent alliance, but there’s no firm decision by story’s end.

The narrative is not about decision or action, anyway, but about feelings. What passes for action is mostly talk. And what talk it is! The dialogue is intellectual, worldly-wise, full of literary and historical allusions expressed with the sort of grammatical and stylistic perfection that I don’t believe ever emerged from the mouths of real people (OK, I’m the realistic type). Even the waiter in their favorite café is a garrulous intellectual. Aciman (a professor of literary theory and specialist in Proust) last year told a New York Times writer, “Many writers I know write about what is real, and I applaud them. I’m more interested in what is true.”[1] Tepid applause, that, with a sniff of condescension. And BTW: can what is real be untrue?

A sample of dialogue from “Room on the Sea,” Paul speaking:

“Maybe what keeps me alive at this point is waiting for something unforeseen to come along. Call it retirement-plus. Good or bad doesn’t matter, so long as it’s a new leaf. My dream: to go to Greece and Italy, but mostly to visit the sites mentioned by Thucydides and Livy. I want to see Lake Trasimene for myself and understand how so many Romans could have perished so needlessly at the hand of the Carthaginians, or go to Plataea, which withstood Sparta for a while but whose women were finally sold into slavery and the men were put to death after none could answer what he had done to serve the cause of Sparta in its long war against Athens.… These things don’t go away because they happened more than two thousand years ago. Nothing goes away, including, as I’m starting to find out, the things we wished had happened but never did. Those rankle and stew in our hearts just the same, and if I were a shrink, I’d say they continue to goad us even when we’re sure we’ve all but put them behind.”

Later, Catherine says,

“We needed to be near the edge and almost dried of blood to welcome what we know can so easily be taken away from us now. Are we perfect? No. Are we good for each other? Who knows. Is this more than just friendship or is this Browning’s love among the ruins? I can’t tell. It’s all we’ve got. Your office, my patients, our children, and of course our spouses – do they matter? Of course they do. But over and above them hover Heathcliff and Catherine, grown much, much older and carrying Medicare cards and senior citizens’ MetroCards.”

Thucydides, Livy, Browning, Emily Brontë. These impressively crafted utterances sound to me more like voices out of an 1880 Henry James novel (or the imagination of a Proustian professor) than unrehearsed conversation between a couple of contemporary upper-class New Yorkers. But perhaps they’re true, if not real.

The third novella, “Mariana,” like the others, is mostly talk, only here the talk is all in one mind. Mariana is a graduate student spending two months at an unnamed Italian literary academy. Raised as “a good Catholic girl from Middle America” (why are “good girls” who go naughty always Catholics? Are there no Jewish or Methodist “good girls” worth writing about?), Mariana falls immediately into a wild fling with Itamar, an enticing airhead who dumps her when inevitably he loses interest and picks up someone new. The story consists entirely of Mariana writing furiously (seemingly in her head, but possibly on paper or in an email) an accusing letter to the faithless Itamar. For example,

“I have no shame. We held nothing back. What I miss now is not just you. What I miss is not holding back. It’s me I miss, the me I didn’t know existed and that you pried out of me like a misshapen mollusk finally eased out of its shameful little slough, because you didn’t care either, and I liked that you didn’t care, because not caring is what I needed in our dark little world. … A month now, and I already feel something has died in me. My skin is dry again, I am listless all over, I feel nothing, my thoughts wither, I have no thoughts. I can’t focus except on what I want to say to you. I want to fight with you, and even then I never know what I’d say. I can’t think – everything feels encrusted; my voice smothers words you made me moan once….”

Wait – a misshapen mollusk? What would that be? A square clam?

That’s about it: on and on, 53 pages of ranting and fulminating in this white-hot tone, but no resolution, conclusion, action, satisfaction. “In one month, one year,” she writes at the end, “who will I be, how will I look back on all this? Will I still ache, will I still want to ache, will there be someone new, or will I look back on this one season in hell and say I was better off then than I am today, I was alive at the time, now what am I? … I know I’ll never send this letter. But I won’t throw it away.” Of course not – she’s a writer. It’s so eloquent, so publishable.

In an afterword, called a “postface,” Aciman explains the genesis of this story. He was reading The Portuguese Letters, a classic seventeenth-century lament supposedly written by a young nun seduced and abandoned by a French officer. Her name was Mariana and, Aciman writes, “I fell in love with her voice,” and eventually “decided to write a modern version.” In other words, here he is writing about writing about writing.

I could be wrong, but isn’t this scenario – the “good girl” seduced by and obsessed with an irresistible rake not worth the trouble – a commonplace? From the original Mariana to Anna Karenina to Emma Bovary and any number of modern iterations? Men do get dumped by shallow women, of course, but don’t often verbally flush their agony in books like this. They head to the bar – “one for my baby and one more for the road” – or worse, do something violent, rather than write self-pitying 50-page screeds with misshapen mollusks in shameful sloughs.

Room on the Sea is impressively crafted and written, but its lack of bite, drive, and action left me restless. Its central characters, intelligent and articulate as they are, don’t do much except think, feel, and talk. Give me a Knicks (or Celtics) game any day.

David Mehegan is the former Book Editor of the Boston Globe. He can be reached at djmehegan@comcast.net.

[1] NYT profile by Leah Greenblatt, Oct. 21, 2024, included with the book’s publicity material.

Great review, David. It held me and gave me adequate chance to decide whether or not to read Andre Aciman’s newest. I think I’ll pass on the book–so many, so little time, etc.–but I’m going to continue to mull the implications of “true” and “real.”