Book Review: “Melting Point” — Promises, Promises

By Debra Cash

After discarding a conventional draft – lots of explanatory narration from the author as a book’s omniscient narrator, looking back at history and knowing how things will turn out – Rachel Cockerell decided instead to create the book entirely as a collage of fragments from the historical record.

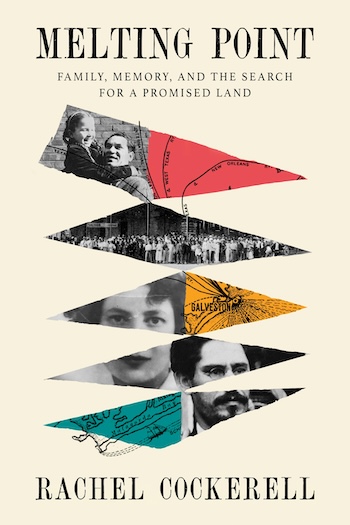

Melting Point: Family, Memory, and the Search for a Promised Land by Rachel Cockerell. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 416 pages, $32

Have you ever wanted to be in the room where something of world-changing significance happened? Do you appreciate counterfactual scenarios?

Have you ever wanted to be in the room where something of world-changing significance happened? Do you appreciate counterfactual scenarios?

Dear reader, do I have a book for you! And the backstory is almost as interesting as the 400+ pages on offer in Melting Point: Family, Memory, and the Search for a Promised Land.

After a family birthday party in 2015 that brought together relatives from Israel she had never previously known, Rachel Cockerell, a young historian born and raised in London, decided to embark on writing a family memoir based on the unconventional living arrangements of her bohemian grandmother Fanny and effective, “easily trod upon” great-aunt Sonia. The two Russian Jewish sisters had lived in a sprawling mansion in North London at 22 Mapesbury Road, and raised their seven young children together (Fanny had four, Sonia three). Their lives diverged when Sonia’s family made aliyah to Israel soon after the establishment of the state. Cockerell, diligent researcher that she was, knew the story had to have started earlier: how had these women come from Kyiv to London, and why?

No one had ever spoken much about their father, her great-grandfather, David Jochelman (sometimes spelled with two ns). Was he a businessman? In finance? Or in insurance? His oil portrait remained in the family living room, glaring down from the wall. Reflexively, she typed his name into Google. The startling results took Cockerell down a rabbit hole to a research project in which her ancestor was, in the words of a New York Times reporter, “the Zelig of early Zionism.”

You may be aware of the name — and world-historical stature — of Viennese journalist Theodor Herzl. Charismatic — observers often compared his brooding looks to those of some ancient Assyrian king. Like many middle-class and educated Jews of his time, Herzl had left traditional Jewish religious observance behind. But, as he argued in his wildly influential 1896 pamphlet Der Judenstaat (A Jewish State), he was convinced that Jewish safety depended on self-sovereignty.

Making a “return to Zion” — to the area then called Palestine under the rule of the Ottoman Empire and after that, the British Mandate — was contested among the early Zionists themselves. Some who attended the series of Zionist Congresses in Basel and London held out for a return to Palestine, as had been expressed in daily prayers for millennia. Others, especially after the brutal pogrom in Kishinev, Moldova, which began on Easter Sunday in 1903, felt that mass emigration to any intermediate landing place was urgent.

And here Cockerell’s story becomes curiouser and curiouser. Along with the idea that Eastern European Jews should emigrate to Uganda, Australia, or Paraguay, there was the proposal that Jews could find safety, “self-respect, and the practice of self-government while waiting for the return to Zion” — in, of all places, Galveston, Texas.

Cockerell’s great-grandfather was one of the project’s key enablers. New York’s Lower East Side — what many would-be Jewish emigrants considered the real America — was overcrowded; German-Jewish financier Jacob Schiff was at first secretly and then publicly ready to put his money down to stem the flood in the service of creating a modern American Jewish citizen who would throw “off the shackles, the peculiarities and prejudices which have handicapped their fathers.” The target area had to be away from the Eastern seaboard. San Francisco was too far; New Orleans might be too seductive. Galveston, part of what was perceived as the wide-open American west, had its own romance. But Jochelman was enterprising, setting up 150 information centers across the Russian Pale of Settlement.

This territorialist effort was facilitated by a polyglot local rabbi named Henry Cohen, described in The Jewish Voice as

casually spattering languages as a machine gun spatters lead, acting instantaneously as father, confessor and adviser to men [sic] of all sorts and conditions, proving at the cost of infinite work and worry his belief in the ancient commandment “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.”

In the seven years of the Galveston project (1907-1914), 10,000 Jews made the passage.

Rachel Cockerell. Photo: Curtis Brown

Cockerell may have had very little Jewish education and identity before she started her book, but her narrative is unconsciously and indelibly Talmudic. After discarding a conventional draft — lots of explanatory narration from the author as a book’s omniscient narrator, looking back at history and knowing how things will turn out — Cockerell decided instead to create the book entirely as a collage of fragments from the historical record. Materials from archives across the globe — the one shortcoming in her method is that original materials she draws on all seem to have been written or already translated into English — jostle against newspaper accounts (the Acknowledgments thank the Fulton History website, which offers digitized versions of US newspapers dating back to 1795!) and interviews she conducted with her relatives, especially her effervescent, still-sharp-as-a-tack nonagenerian aunt Jo, who was living in Canada by the time she began her research.

Unlike a page of Talmud, there is no central text around which her widely sourced impressions congeal, but there are a few central characters, in particular Israel Zangwill, “the Dickens of the Ghetto,” who in his time was among the most famous writers in England and founder of the Zionist splinter group that called itself ITO, the Jewish Territorial Organization.

Readers of Cockerell’s memoir can enjoy a kind of fly on the wall experience of how Zangwill came across. She quotes a writer for The New York Journal, describing him in 1898.

The first impression one gains of Israel Zangwill is that he is the ugliest man in the world.… His necktie was an affair to make a careful dresser dive to the depths of the ocean … [but] He is a “skimmy” talker, flitting from one subject to another with the agile grace of the man who jumps over a long line of elephants in the circus, touching each elephant with his toe as he sails towards the mattress.

Zangwill stands in a long line of Jewish writer/activists. The samples of his writings threaded through the composite narrative demonstrate both his sense of desperation and his ability to turn a memorable phrase. Take, for instance this excerpt from a speech to the Seventh Zionist Congress in 1905:

If we gave up this chance, I know not when we shall have another. It will prove the salvation of tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of wandering Jews. When [the British offer to create a Jewish homeland in] East Africa is gone, you will be glad that the aching tooth is out, but afterwards you will remember that it was your only tooth. I beg you to ponder these things before you reject the greatest opportunity the Jewish people has had for eighteen centuries.

Of course, we have the hindsight to know that the territorialist option didn’t pan out, and that the numbers of Jews who were not saved numbered not in the hundreds of thousands but the millions.

The Galveston project stands at the center of Cockerell’s remarkable narrative, but there are wonderful digressions to fill out this idiosyncratic volume. One is her recounting of the anarchic lives that unfolded at 22 Mapesbury Road — including the early childhood of her father. The other is the high-minded goings-on of David Jochelman’s son from an earlier marriage, Emmanuel “Emjo” Basshe, who created an experimental theater troupe, The New Playwrights’ Organization, with four pals including the already famous John Dos Passos. Intended to eschew the “impotent middle class [and] the perfumed social register” but underwritten by a well-heeled banker and president of the Metropolitan Opera Board, Otto Kahn, the theater may have tried to speak for the working class but instead bored them, and generated reviews like that of a New York Herald Tribune critic who noted “after seeing two of three such plays, one […] sobs for ear muffs and aspirin.” (The abstract to a later scholarly article, which Cockerell does not quote, reads, “Its works were among the most boisterous and futile ever witnessed in the smaller playhouses of New York, and its record of acid notices and early closings has not been broken in some thirty subsequent seasons of off-Broadway production.”)

Based on the evidence of her graceful preface, afterword, and the uncommonly interesting acknowledgments included in Melting Point, Rachel Cockerell is a talented writer. It’s impossible to tell how well she can sustain an entire narrative in her own voice.

But my god! The woman can edit.

Rachel Cockerell is on an in-person and online American book tour, with one upcoming Zoom event of special interest.

Debra Cash, a Founding Contributing Writer to the Arts Fuse is a member of its Board.