Theater Review: “The Obligation to Live” — Defying the Machinery of Death

By Robert Israel

The emphasis of the B&P troupe has become increasingly apocalyptic: the struggle we are engaged in is for nothing less than the preservation of our planet, and for the preservation of our individual — and collective — hearts and minds.

The Obligation to Live. Performance conceived and directed by Peter Schumann and the Bread and Puppet Theater collective, Center for the Arts, The Armory, Somerville, April 24. Closed.

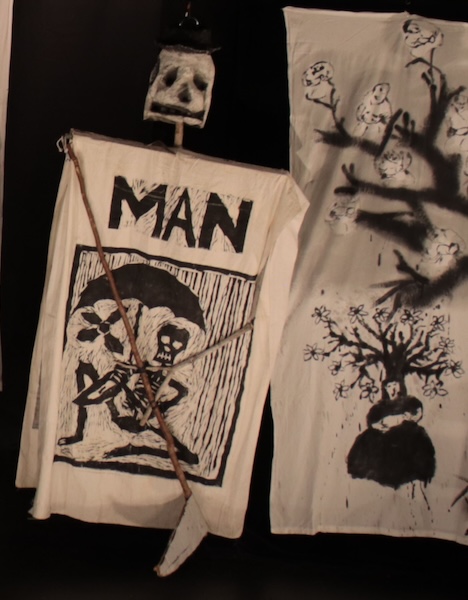

A scene from Bread & Puppet Theater’s The Obligation to Live. Photo: courtesy of the artist

While the audience took their seats at The Armory, they were serenaded by “The Ultimate Decline of the Capitalist Empire! Brass Band,” an eight-piece ensemble that included a bass drum. They played tunes like “Has Anybody Seen My Gal,” and “Red River Valley.” But the theatergoers didn’t need a musical welcome to rev them up: they arrived buzzed. A visit by Bread & Puppet Theater, who started out the company’s Spring tour on March 27 in its big yellow school bus from Glover, Vermont, is a highly anticipated yearly event. The band — doubling as players/puppeteers — is dressed all in white, radiating red cheeks and ebullient spirits. They deliver a show heavy on gaunt portents, but not without glimmers of light and hope.

I have been following B&P since 1969, when, as a befuddled high school student facing conscription in the Vietnam War, I met the troupe when they yanked me onstage at the Newport Folk Festival. I credit them with helping me take an alternative path, an alternative that my then 17-year old mind might not have fathomed. As Joan Baez sang protest songs, I and the other concertgoers howled off-key to drums, trumpets, tubas, and trombones. We held antiwar posters aloft. When I returned to my seat, I discovered a newfound exhilaration and clarity. I’m not alone, I thought, maybe, just maybe, I’ll beat this mess.

B&P has been helping audiences to find a way out of inhumane political messes ever since. They continue their protests against war and a plethora of other universal scourges, such as the destruction of our fragile climate, poverty, lack of basic human necessities, and the forced imprisonment of immigrants, to name a few. An early appearance by a ghostly papier-mâché Grim Reaper puppet sets the tone — he is wearing a sash that reads “Man.” We’re in for it. We increasingly face seasons of darkness and “distress” that we need, somehow, to turn into “success” if we are going to survive.

A scene from Bread & Puppet Theater’s The Obligation to Live. Photo: courtesy of the artist

B&P is still guided by the 92-year-old visionary artist Peter Schumann, who, along with the ensemble, created the show, which features snippets from a wide swath of texts, including Popol Vuh, The Maya Book of the Dead, Franz Wiedemann’s Hänschen klein (“Little Hans”), and poems by Palestinian-American physician and writer Fady Joudah (“Dedication”), and the American author and activist Grace Paley (“People in My Family”). The music draws on Austrian composer Anton Webern’s Kinderstück (“Children’s Piece”). Given Schumann’s advanced age, many wonder what direction the troupe will take when he passes. Founded just over 60 years ago, it remains one of the few surviving political theater troupes that arose in the ’60s, an engaged cadre that once included the ProVisional Theatre of Los Angeles, the Snake Theater of Sausalito, and the Powderhorn Puppet Theatre of Minneapolis.

B&P remains true to its mission: to create works that implore us, as theatergoing citizens, to question our government when it is betraying its legal and moral obligations, as well as an economic system that runs on inequality, the death of innocents, and environmental destruction. Back when the Vietnam War was raging, B&P publicly decried the “fog of war.” Today, they urge us to go further, to dig deeper and harder. It’s not enough to visit the ballot box, they insist: we must take action against dominating bullies and lethal con men with renewed vigor. We must challenge the political machine by taking our protests to the streets and then some. Here are the last two stanzas of Paley’s poem, which is quoted in the show’s program:

The ninety-two-year-old people remember

it was the year 1905

they went to prison

they went into exile

they said ah soon

When they speak to the grandchild

they say

yes there will be revolution

then there will be revolution then

once more then the earth itself

will turn and turn and cry out oh I

have been made sick

then you my little bud

must flower and save it

I am impressed by the performers’ vigor. They borrow heavily from Japanese Kabuki theater, ringing bells and banging tin plates to create discordant sounds that alert us to scene changes. Look closely at the nimble players who serve as kurogo — black-clad stagehands. They manipulate the giant puppets from underneath and enable them to perform various theatrical tasks. The company’s creativity remains earthy and inventive: all the puppets are handcrafted, the bed-sheets hand-painted, the props cobbled together from birch boughs and hemp. The overall effect is to accentuate a powerful authenticity.

The emphasis of the B&P troupe has become increasingly apocalyptic: the struggle we are engaged in is for nothing less than the preservation of our planet, and for the preservation of our individual — and collective — hearts and minds, a humanity that, as memorably visualized in The Obligation to Live, is being tossed by too many into garbage cans.

Leaving Somerville’s Armory, I recalled this quotation from the late columnist Doris Fleeson: “I wish I had some magic formula to suggest. There is none. There are no wonder men or wonder women. There are only you and I and others who believe in freedom.”

Robert Israel, an Arts Fuse contributor since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

I will add to Bob’s review that this year’s show seemed to me to not be able to rise about its strong evocations of horror. The predominance of Man as the Grim Reaper couldn’t overcome an attempt to provide uplift at the end. It is symptomatic of a need for theater that does not need (structurally) to wait until the end to drum up encouragement. Drawing on the words of Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han, hope might be dramatized in a way in which it “confronts the world in its full negativity and files its objections.” Once those have been made, it might be possible “to take the leap towards a new life.”

The tragic plight of the decimated Palestinians of Gaza (and by extension the West Bank) was the most obvious inspiration for the show – that alone elevated B&P’s The Obligation to Live to a moral plane above much of what is being presented on Boston stages and elsewhere, despite their proclamations of the value of empathy.