Book Review: “Stanley Kubrick: An Odyssey” — One of the Cinema’s Most Profound Seers

By Tim Jackson

For fans of director Stanley Kubrick, this enhanced biography may be the most thorough and readable volume on one of the cinema’s most profound seers.

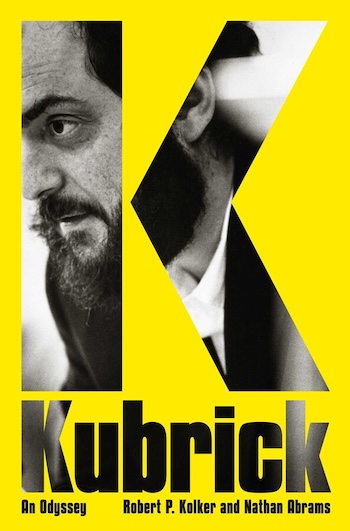

Stanley Kubrick: An Odyssey by Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams. Pegasus Books, 656 pages, $20

Information about the life and career of director Stanley Kubrick is abundant, available in biographies, memoirs by associates, interpretations and analyses of his films, and via YouTube videos where actors, directors, critics, and enthusiasts discuss his influence and analyze his style. So the recent release (in paperback) of the 600-page biography Kubrick: An Odyssey would seem to be mammoth overkill. But Robert Kolker and Nathan Abrams, building on their previous studies of the filmmaker, along with 29 dense pages of sources and a lucid chronology of Kubrick’s doings, generate plenty of rewarding insights into an unparalleled body of work. Kubrick’s 13 films were the result of dogged research and production times that could stretch into months and years. His intense focus on every aspect of making a film no doubt contributed to his reputation as cold and exploitative. But, while Kubrick could wear out assistants, partners, and producers, exhaust film crews, and even endanger his actors for the sake of achieving his goals, the book offers a softer side of the director, pointing out that he was a devoted family man and a lover of pets.

Like his best films, which skillfully balance a grim view of human nature with offbeat humor, Kubrick was a fascinating paradox. The Jewish son of a doctor, he spent most of his life avoiding physicians. His formative years were spent among the poets and artists of bohemian Greenwich Village, but his approach to art was deeply scientific. Photography and filmmaking were his tools for controlling as well as understanding the world. In the notes of an early screenplay, here is how Kubrick mused about a fictional character, who was a photographer: “He often thought … that life could only be understood by looking backward … and stopping life, as in his photography.”

Two brief marriages to talented women contributed to his early work, but domestic life did not fit his obsessive personality. He then married Christiane Kubrick (née Harlan) in 1958, and they remained together until he died in 1999. She was the niece of the Nazi-era filmmaker Veit Harlan, director of the notorious film Jud Süß. She called her background “a heavy burden I have carried since childhood.” She was an actress and singer (appearing in Paths of Glory) and became a talented painter who garnered international renown. “Stanley and I … came from such grotesquely opposite backgrounds,” confessed Christiane, and Kubrick was intrigued by that background. He planned to eventually direct The Aryan Papers, a Holocaust film based on the 1991 Louis Begley novel Wartime Lies. That movie was never completed. The idea was also overshadowed by the release of Steven Spielberg’s film, Schindler’s List, which Kubrick admired. Christiane said of her husband’s approach to the Holocaust: “Stanley could not instruct actors how to liquidate others and could not explain the motives for the killing. “I will die from this,’ he said, “and the actors will die too, not to mention the audience.” His relationship as a Jew to the German atrocities taught him a lesson that carried through his life: “Never go near power. Don’t become friends with anyone who has real power. It’s dangerous.”

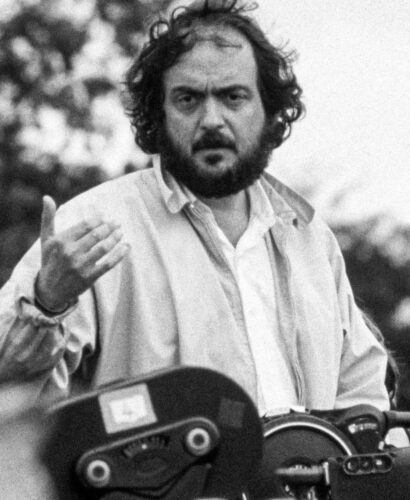

Stanley Kubrick on the set of Barry Lyndon. Photo: Wiki Common

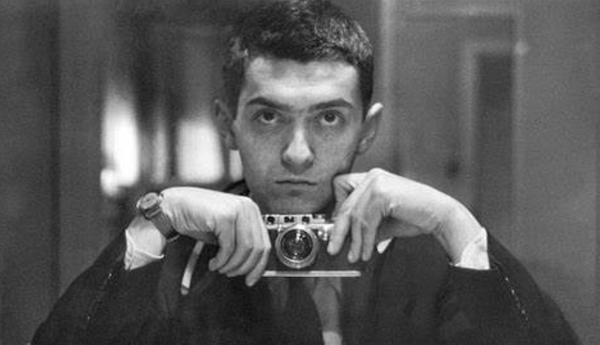

Kubrick’s early passion for jazz drumming was quickly overtaken by his keen eye for photography (he even set up his old drum kit at his English estate while shooting 1979’s The Shining). He was 17 when he sold his first photograph to Look magazine. The 26,000 pictures he took while on the staff of Look formed the basis of his film work. His early interest in making films began with his admiration for Sergei Eisenstein and Charlie Chaplin. He liked the Russian director’s sense of composition and editing, but felt his movies were wooden. “Eisenstein is all form and no content, whereas Chaplin is all content and no form” Kubrick declared. That assertion is arguable, but one can see in Kubrick’s work attention to formal composition, accompanied by an appreciation of antic comic theatrics shown by Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove, Malcolm McDowell in Clockwork Orange, Lee Ermey in Full Metal Jacket, or Jack Nicholson in The Shining. George C. Scott, playing General Buck Turgidson in Dr. Strangelove, was angry that Kubrick chose his most buffoonish takes for the final edit of that film.

Challenges in producing, directing, and editing were present from the start of Kubrick’s career, including his first film, Fear and Desire. After borrowing $5,000 from his uncle for a film originally to be called The Shape of Fear, he attempted to save money by rerecording all the dialogue, sound, and music in postproduction. That called for the actors to match their lip movements. “I just didn’t have enough experience to know the proper and economical approach,” Kubrick later said. Critics considered it to be a B movie. Kubrick hoped his film would be forgotten, but it was later rediscovered and is now considered an essential part of his evolution. Despite the challenges, reviewers and producers began to recognize Kubrick’s unique eye for lighting, composition, and structure.

Fear and Desire is about a group of soldiers stranded behind enemy lines (it presages 1957’s Paths of Glory). It contained two themes that interested him: war and human psychology. Also, among his stacks of paperbacks and books at this time was a copy of Arthur Schnitzler’s novella Traumnovelle and the fiction of Stefan Zweig. These are Jewish writers whose intense, Freudian interest in the interplay of psychology and relationships — “what made them tick and what made them crumble” — fascinated Kubrick. Traumnovelle became an obsession, eventually leading to his final film, Eyes Wide Shut.

James Harris, who had family money and ambitions as a producer, was impressed by young Kubrick’s ability to self-produce and direct good independent films. The two became partners in 1955 under the title Kubrick-Harris Pictures. “If I did anything for Stanley it was to accelerate his career. The talent was always there,” said Harris. After poring over several detective novels, the two settled on Jim Thompson to work on a screenplay called Sudden Death, based on a novel by Lionel White. The narrative would be told from multiple perspectives, in the manner of films such as Rashomon and Citizen Kane. Kubrick’s interest in Jean-Paul Sartre and existentialism, a hot topic in the ’50s, was part of his inspiration for the film, which was eventually released as The Killing. The original script had been turned down multiple times by potential producers because it was considered confusing — until Kirk Douglas read it. The actor’s initial reaction to Kubrick is typical of the first impression he left on others who met him about developing scripts or buying properties. “He looked like a basset hound with those big sad pouches. What I didn’t understand was that a sleepy appearance belied a man who is always awake always thinking,” recalled Douglas. “Kubrick infuriates you when you first work with him. How can he know so much so soon? Then you settle down and admire him.” Douglas told Kubrick that he didn’t think the film would “make a nickel,” but it had to be made. Thompson had added key elements to the story and character relationships, but the final film listed Kubrick as the sole screenwriter. Thompson was credited with “additional dialogue.” The writer was furious.

Stanley Kubrick when he was working for Look magazine.

Douglas would go on to hire Kubrick for Paths of Glory, based on a novel by Humphrey Cobb. Despite their falling out over the credits for The Killing, Kubrick went back to Thompson, who wrote the script with Calder Willingham (he would go on to write One-Eyed Jacks, The Graduate, and Little Big Man). Kubrick tended to employ writers until they conflicted with his vision. As his reputation grew, writers put up with the cursory treatment — it became an honor to work with the director, despite the risks and demands he imposed.

On the set of Paths of Glory, Douglas and Kubrick fought often. The director could require as many as 40 takes. Actors were becoming sick from the wet and cold in the trenches (it was filmed in West Germany, with the main locations being around Munich) or suffered from burns after explosive charges went off in the battle scenes. He earned the moniker Stanley “Hubris” because of his willingness to stand up to Douglas to get what he wanted. Kubrick’s insistence on perfection lasted throughout his career.

On Kubrick’s next film, Lolita, his penchant for multiple takes did not work as expected. Shelley Winters, hired initially because of her star status, played Lolita’s mother. Peter Sellers, who Kubrick greatly admired, was cast as Claire Quilty. In one scene, Winters could not remember her lines. They went through 45 takes. Sellers, a master of spontaneity, was brilliant early on, but by the time Winters finally had her lines down, Sellers would blow his. The scene had to be fixed during editing. Actors in subsequent Kubrick productions assumed that they could be quickly replaced if they did not know their lines.

Kubrick’s early films offer insight into his obsessions. Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb grew out of his genuine fear of nuclear annihilation. His extensive research for that film became typical of his creative process, even for projects that never came to fruition. With Strangelove, his research led him to the conclusion that the subject was too unbelievable for a drama, but that it could be molded into a great black comedy.

A scene from 2001.

His preoccupation with extraterrestrial life led to 2001, based on Arthur C. Clarke’s novel. His research on space travel made him reject the then standard “earth vs aliens” cliché and embrace a futuristic vision that some consider his most outstanding cinematic achievement. Critics, at first, were not kind. Pauline Kael, not a fan of Kubrick, (she would later dismiss Clockwork Orange as “psychedelic fascism”) published a review that “bordered on brutal.” Even Clarke, with whom Kubrick had collaborated, “was shocked by the film’s transformation.” Kubrick’s reaction: “Perhaps there is some element in the lumpen literati that is so dogmatically atheist and earthbound that it finds the grandeur of space anathema.” In a rare interview, the director attempted to explain the famous “star child” ending: “The idea is supposed to be that he is taken in by God-like entities, creatures of pure energy and intelligence with no shape or form, who put him in what can be described as a human zoo. His whole life passes in that room. He has no sense of time; it just seems to happen. As it does in the film.” 2001‘s out-of-this-worldliness appealed to the ’60s generation, and lines for the movie were around the block.

Early stories about 1975’s Barry Lyndon attest to Kubrick’s passion for the flawless. The director was unable to determine how to shoot a scene until he saw its set fully dressed and lit. He didn’t like stand-ins for lighting. Actors in full costume were often subjected to hours in the heat of the lighting equipment. At one point, star Ryan O’Neal had to be administered oxygen. Kubrick counted on his actors to deliver authentic performances; his directions would mostly be “Do it faster, do it slower, do it again.” Mostly, it was “do it again,” recalled featured actor Patrick McGee. Kubrick moved the entire production from Ireland back to England when the IRA threatened his life because it was affronted that he was using Irish actors to play British soldiers while shooting on Irish soil. Kubrick informed the movie studio of this only after the entire move had been completed at an enormous cost. That called for significant insurance payouts. Frequently, Kubrick would finagle such payouts as a way to help with production costs. Aware that his demands could overrun production budgets, he was a stickler for scrimping on costs and for keeping and overseeing meticulous expense accounts. In fact, the demands he put on himself may have led to the heart attack that killed him at age 70.

A scene from Barry Lyndon.

The films that Kubrick never got around to completing are well known. In addition to The Aryan Papers, there was Stefan Zweig’s The Burning Secret and several unreleased screenplays. For Napoleon, research went on for years: the exact location of battles, the food, and even what kind of soil was on the grounds of specific battles. Ultimately, even he found the sheer scope of what needed to be done too daunting. (Ironically, an epic production, Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, fell flat because it didn’t have the balance Kubrick maintained between drama and humor.) Kubrick’s idea for a movie about Artificial Intelligence, inspired by Brian Aldiss’s short story “Supertoys Last All Summer Long,” was eventually completed from Kubrick’s notes by Spielberg. That adaptation, released under the title AI, reflected Spielberg’s commercial style rather than Kubrick’s dark vision.

Kubrick disliked critical interpretations of his films and was wary of what the press claimed to understand about this work. Still, he was sensitive to reviews. In a 1967 essay, “The Death of the Author,” Roland Barthes wrote, “To give an author to a text is to impose upon that text a stop clause, to furnish it with a final signification, to close the writing.” Kubrick was nothing if not a control freak of an author: he did his best to ensure that his vision remained pure and was diligent regarding every aspect of his productions, from research to distribution. With the tireless help of his assistant Leon Vitale (well-profiled in the movie Filmworker), Kubrick was a hands-on decision maker, from publicity and posters to overseeing prints of his films.

Kubrick: An Odyssey’s 31 chapters are arranged chronologically and built around the development of each film. For fans of the director, this enhanced biography may be the most thorough and readable volume on one of the cinema’s most profound seers.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter-skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story. And two short films: Joan Walsh Anglund: Life in Story and Poem and The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog

Tagged: "2001", Nathan Abrams, Robert P. Kolker, “Stanley Kubrick: An Odyssey”