Book Review: “Passion” Project — Pedro Almodóvar as Consummate Auteur

By Peter Keough

Though lapsing at times into hagiography and muddled synopsizing, James Miller’s study of filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar is a bracing reminder of the greatness and ever-evolving genius of this world-class artist.

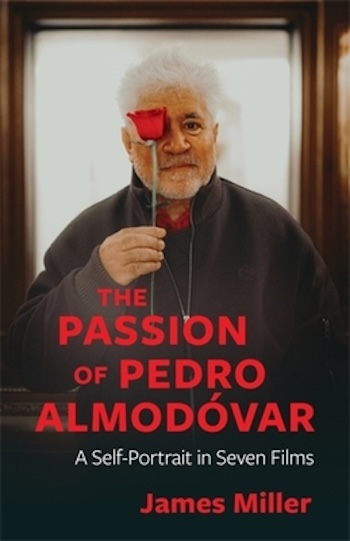

The Passion of Pedro Almodóvar: A Self-Portrait in Seven Films by James Miller. Columbia University Press. 216 pages. $25.99

Those whose only exposure to the brimming oeuvre of 75-year-old Pedro Almodóvar was his most recent film The Room Next Door (2024) — a polished, anodyne effort like a second-rate Todd Haynes melodrama — would most likely receive a better introduction by reading James Miller’s insightful though at times meandering The Passion of Pedro Almodóvar: A Self-Portrait in Seven Films.

Those whose only exposure to the brimming oeuvre of 75-year-old Pedro Almodóvar was his most recent film The Room Next Door (2024) — a polished, anodyne effort like a second-rate Todd Haynes melodrama — would most likely receive a better introduction by reading James Miller’s insightful though at times meandering The Passion of Pedro Almodóvar: A Self-Portrait in Seven Films.

There you might read about the Spanish auteur’s debut feature Pepi, Luci, Bom and Other Girls on the Heap (1980), a scatological cross between The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and the early films of John Waters. It opens with a rape played for laughs, includes an impromptu golden shower, a coerced public blow-job, and a character who enjoys being beaten by her husband.

After the film’s 1992 release in the US, Janet Maslin wrote in the New York Times, “a rough unfunny comedy notable for its bathroom jokes, humorous rape scene, and abysmal home movie cinematography.” Rita Kempley noted in the Washington Post that “Pedro Almodóvar showed not a whisker of promise in his amateurish directorial debut, a smutty sexual sideshow most safely viewed in a full body condom.”

But by then, of course, Almodóvar had ascended to the cinematic pantheon with rollicking international hits like Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1991) and What Have I Done to Deserve This? (1984). And though panned at its release by most critics, Pepi nonetheless was a popular sensation, establishing Almodóvar as a daring, taboo-shattering filmmaker at a time when the post-Franco culture was enjoying its own belated, anything-goes countercultural renaissance.

Miller identifies the raucous environment of the era as one of three keys to Almodóvar’s artistic development. The other two are Almodóvar’s provincial childhood and relationship with his mother, as explored in Volver (2006), and the traumatic abuse he experienced while a student in a Catholic boarding school run by Salesian fathers that he confronts in Bad Education (2004). But, according to Miller, unlike the other two films, which were made long after the actual events, Pepi is distinguished by the fact that it sprang up as Almodóvar was experiencing the wildly transgressive and artistically fecund scene the movie depicts. It was a sybaritic time that, as can be seen in that raw first film, pushed id-like impulses and the desire for personal freedom to the point where their limitations and contradictions were exposed, conflicts which became the obsessions of his subsequent films.

Fortunately, given Miller’s penchant to recount in detail Almodóvar’s convoluted plots, you don’t have to actually see Pepi to get the point. But such summarizing becomes less helpful as the films grow more complex, reflexive, and accomplished. In these increasingly layered and labyrinthine movies, keeping track of the narrative becomes a growing challenge (as Roger Ebert writes in the beginning of his Bad Education review, “I was attempting to describe the plot.… It was quicksand, and I was sinking fast”), but less of a requirement.

Instead of the storyline, the play of ideas and the elegance of the form become paramount. As Miller observes, “with the advent in the 1980s of the modern home video technologies …Almodóvar knew that viewers … could easily see his films more than once.… His film plots became baroque, and his story lines suggestive of the countless intractable and sometimes tragic dilemmas that surround the question of what constitutes a good life, as richly suggestive in their own idiosyncratic way as the ancient narrative fictions that first gave a name to the vocation we still call ‘philosophy.’”

Miller goes on to trace the development of this self-examining, philosophical trend in Almodóvar’s work, from Law of Desire (1987) and The Flower of My Secret (1995) to Broken Embraces (2009) and finally, his masterpiece, Pain and Glory (2019). A professor of politics and liberal studies at the New School for Social Research and the author of Examined Lives: From Socrates to Nietzsche (2011) and The Passion of Michel Foucault (1995), the critic unloads lots of heavy references and comparisons, from Plato to Andy Warhol, Nietzsche to David Bowie, as he makes his case that Almodóvar is “the first compleat art cinema auteur” and “one of the most important artists with a self-conscious interest in moral philosophy to have emerged from the global counterculture of the 1960s.” Though lapsing at times into hagiography and muddled synopsizing, Miller’s study is a bracing reminder of the greatness and ever-evolving genius of this world-class artist.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Tagged: "The Passion of Pedro Almodóvar: A Self-Portrait in Seven Films"