Classical Music Album Review: Brahms & Schumann and Mozart & Bruch

By Jonathan Blumhofer

It is serendipitous that James Ehnes added Brahms’s two viola sonatas to his repertoire; Patrick Messina, Lise Berthaud, and Fabrizio Chiovetta’s new recording of Bruch’s “8 Pieces for Clarinet, Viola, and Piano” serves the piece admirably.

That Johannes Brahms wrote two viola sonatas is one of the happy accidents of Fate. That James Ehnes has added them to his repertoire is equally serendipitous.

That Johannes Brahms wrote two viola sonatas is one of the happy accidents of Fate. That James Ehnes has added them to his repertoire is equally serendipitous.

Composed after the German master’s short-lived retirement in 1890, the set was originally intended for the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld. Brahms transcribed them for viola but, evidently, wasn’t satisfied with the end result: “I fear that the two pieces are very clumsy and ungratifying” for viola, he wrote to his old friend, violinist Joseph Joachim.

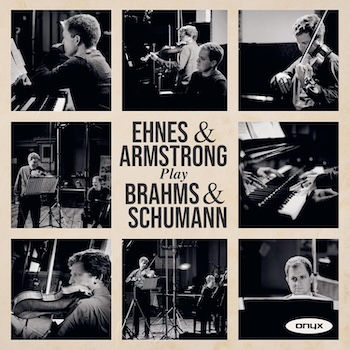

If only he could have heard these richly focused and impassioned performances from Ehnes and pianist Andrew Armstrong. Nothing sounds unidiomatic, forced, or ungainly. Instead, these are about as natural, flowing, and expressively direct readings of these two chestnuts as one is likely to hear. Ehnes proves to be at least as good a violist as he is a violinist, drawing dexterous rhythms and sumptuous tone from his instrument.

In the F-minor Sonata (No. 1), the Canadian-born artist imbues the music’s tempestuous turns with fervency. Yet a graceful songfulness is never far removed, as his take on the luminous Andante attests. The Sonata No. 2 fares similarly: gorgeous and lush, but ever on-point rhythmically and expressively. In both works, Armstrong’s contributions are just as compelling — shapely, lean, and faultlessly weighted.

In fact, the compatibility of this long-time pairing’s ensemble is one of the album’s delights. Just listen to how they navigate the complexity of the F-minor Sonata’s opening movement: rarely do its intricate layers of thematic, motivic, harmonic, and rhythmic gestures sound so, well, approachable. For textural clarity and character, too, their Brahms — both in the Sonatas and the filler of the composer’s famous “Lullaby” — is wonderfully fresh.

The pair’s account of Robert Schumann’s Märchenbilder is likewise engaging. Written in 1851, these four character pieces can sound a bit austere, though Ehnes and Armstrong warmly tease out the little things (like the opening movement’s turns and mordents) while also emphasizing the music’s bigger plays of contrast. The central movements — especially the third — push ahead brilliantly. Meantime, there’s a Schubert-like simplicity to the finale’s melodic lines.

The combination of clarinet, viola, and piano is such an inspired one that it’s a bit surprising that the fusion isn’t more central to the chamber music repertoire. Even so, since Mozart wrote his Kegelstatt Trio in 1786, a handful of major composers have, one way or another, dabbled with that instrumentation.

The combination of clarinet, viola, and piano is such an inspired one that it’s a bit surprising that the fusion isn’t more central to the chamber music repertoire. Even so, since Mozart wrote his Kegelstatt Trio in 1786, a handful of major composers have, one way or another, dabbled with that instrumentation.

Max Bruch was one of them. Though his 8 Pieces for Clarinet, Viola, and Piano originally called for a harp instead of a keyboard, the suite traffics, by and large, in the sonorous interaction of those distinctive voices.

In clarinetist Patrick Messina, violist Lise Berthaud, and pianist Fabrizio Chiovetta’s new recording of the work, the best of those qualities — soulful warmth, liquid tonal blend, fervent lyricism — emerge readily. So do the music’s too-few moments of playfulness. The Allegro vivace is spirited and charming while the Allegro agitato snaps.

Perhaps the larger piece would hold more appeal if it involved more such episodes; for all the Brahmsian richness of his style, though, Bruch — especially when he composed the 8 Pieces in 1908 — was the picture of musical conservatism. Accordingly, a sober rigor prevails over stretches of it.

Nevertheless, the Messina-Berthaud-Chiovetta Trio dispatches the score with impressive unity of purpose. The first movement’s rippling keyboard textures emerge lucidly while its pianissimo phrases are consistently well-blended. So, too, the sixth movement’s dovetailing and dynamic shape; here, as well, Messina’s chalumeau-register contributions beguile.

Filling out this short disc is, fittingly, Mozart’s foundational effort, which, on the merits of the current group’s reading, has lost none of its fresh, sunny, conversational vitality in nearly 240 years. Notably, the highlight of their account is the central Menuetto, whose outer thirds dance nimbly, but whose central Trio both moves with purpose and bristles with dry wit and nuance.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Andrew Armstrong, Aparte, Fabrizio Chiovetta, James Ehnes, Lise Berthaud, Onyx