April Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Television

A scene from Season 3 of Yellowjackets. Photo: Kailey Schwerman/Paramount+ with SHOWTIME

The series Yellowjackets started off on such a high note, it was truly thrilling. Yellowjackets is the name of a girls’ high school soccer team in New Jersey. On their way to a competition, their small plane crashes somewhere in the Canadian wilderness, and they’re stranded for over a year. Twenty years later, the survivors continue to struggle with trauma while sensational rumors of the desperate measures they took to survive still persist. The narrative was original, high stakes, complex, suspenseful, and well-written, full of cultural touchstones that melded the past and present. The performances were fantastic.

Season 2 dove deeper, with the addition of more characters who survived into the present. The torturous mental and physical challenges of being away from civilization and at the mercy of cruel nature were acutely probed. But the writing in Season 3 isn’t living up to the previous seasons, which is unfortunate. The dialogue is much more expository, almost embarrassingly so at times, as when Van (Lauren Ambrose) feels the need to remind her lover Taissa (Tawny Cypress) about her terminal illness, which she’s obviously well aware of. A somewhat predictable plot trajectory is developing, in which present-day characters are being stalked and killed mysteriously. The remaining survivors –brought together by their shared secrets — begin to suspect one another. The acting remains top notch, with the younger characters (and performers) really coming into their own as they vie for leadership, creating their own rules and moral structures for control and survival. But their older versions are running in circles, relying on random dreams, visions, and long-buried conflicts to make one transparently bad choice after another. Here’s hoping Yellowjackets survives long enough to resurrect its early brilliance.

— Peg Aloi

Concert

Horsegirl (L-R Penelope Lowenstein, Gigi Reece and Nora Cheng) at Arts at the Armory. Photo: Paul Robicheau

“These spaces are very important,” Penelope Lowenstein of Horsegirl told a March 27 crowd at Somerville’s Arts at the Armory, recalling a similar place in Chicago “where I learned to play guitar.” Along with bandmates Nora Cheng and Gigi Reece, she’s still learning and evolving. Horsegirl hit the Armory on a short U.S. tour (during college spring break for Lowenstein and Cheng) behind second album Phonetics On and On, where the trio builds and deconstructs syllables of indie-rock structure. In its shift from Sonic Youth-inspired guitar clashing to cleaner minimalism under producer Cate Le Bon, the group spins what can seem like charming fragments more than fully developed songs. And live, that approach was laid even more bare within the band’s modest delivery.

Horsegirl played all 11 tunes from Phonetics On and On and three off 2022’s Versions of Modern Performance over a mere hour-long set. Opener “Where’d You Go?” (with drummer Reece accelerating the tempo with harder hits) and “Switch Over” set a blueprint. Cheng and Lowenstein balanced strummy guitar stabs and sparse six-string bass lines while sharing vocals that came across for effect more than lyrical content, threads of repetition floating like mantras. Lowenstein addressed disconnection in “Well I Know You’re Shy” while steering a perkily melodic bass part.

Halfway through the set, the guitarists literally switched it up, trading sides as well as instruments. Lowenstein preset a drone on a synthesizer, then added high guitar licks in “Rock City,” sung by Cheng over an octave-lower plucked note. Lowenstein’s vocal on “Julie” resonated more than her scratched rhythm on guitar muted by a scarf under the strings. “Anti-Glory” lent a welcome hint of post-punk snarl over Reece’s reemphasized thump. Yet four of the last six songs injected variations on “da-da-da” wordless vocals, suggesting that no matter its charms, Horsegirl still faces spaces it may grow to fill more smartly.

–Paul Robicheau

Books

Few Bostonians or visitors to the city need to be told who Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924) was. The museum that she originally built as her home—and as display case for the treasures of art and design that she and her late husband had accumulated—remains one of the city’s most astounding and most-visited sites.

Readers of The Arts Fuse have already been treated to Peter Walsh’s perceptive reviews of an official short biography of ISG and of a book, likewise from the Museum, reproducing many pages from the richly illustrated diaries that “Mrs. Jack” (as she was sometimes known) kept during her extensive travels to Europe and more distant lands.

There has, however, long been need of (as Walsh said) “a full-bore scholarly biography.” Natalie Dykstra now provides this in her detailed yet compulsively readable Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner (available in all formats, including an inexpensive paperback). Readability is eased by an avoidance of footnotes: instead, there are 70 pages of endnotes, keyed to the precise passage of each page of text by a few quoted words, and an informative Note on Sources.

The mysteries behind ISG and her Museum will probably always remain (including the current whereabouts of some major paintings brazenly stolen from the Museum in 1990). But Dykstra’s richly detailed recounting brings us closer than we have ever gotten to this secretive, imperious, yet, in her own way, highly principled art lover—and book lover and music lover. Yes, music was on regularly display in her successive homes, sometimes performed by major opera singers or, on a few occasions, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. (I have explored the role of music ISG’s life in a chapter in this open-access book, and in the 1974 and 1975 issues of the Museum’s former scholarly magazine Fenway Court—now likewise available open-access.)

— Ralph P. Locke

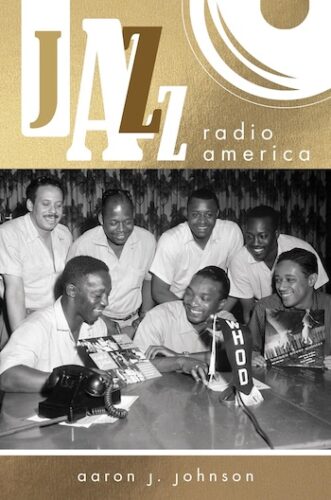

Aaron J. Johnson covers a lot of ground in Jazz Radio America, detailing the rise and fall of stations, their changing formats, the careers of important DJ’s and some radio regulatory activity.

Aaron J. Johnson covers a lot of ground in Jazz Radio America, detailing the rise and fall of stations, their changing formats, the careers of important DJ’s and some radio regulatory activity.

The book links the presence or absence of jazz on radio with the rise and fall of its popularity. Although he considers financial exigencies, Johnson analyzes format changes through a lens that is politically and racially infused. The book’s value is in its historical scope, so that even if one doesn’t necessarily agree with his analysis, one still gets an excellent overall view of the relationship between radio and jazz.

A lot of jazz (or at least dance music/jazz) was heard in early radio days, but it was live. In fact, the 1922 radio act prohibited “mechanically reproduced” programs. There was, however, a program begun by a black radio man Jack Cooper called The All-Negro Hour, on WSBC in Chicago in 1929. Racism actually helped Cooper succeed: Because so much black music was not accepted into ASCAP-American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers-Cooper was able to play “race records of gospel music” without having to pay the high ASCAP fees.

Starting in the 1940’s, jazz became divided into what became known as bop, “traditional,” “mainstream” and jazz that was more influenced by R&B. Johnson describes this bifurcation on radio, with some stations playing jazz that was more critically acclaimed and black stations playing jazz that was more popular in the black community.

From the 60’s into the ’70s, jazz moved increasingly to the non-commercial end of the dial. Jazz was saved, Johnson says, but something was lost. He thinks the traditionalist mainstreamers won out over funk, soul and other types of jazz (including free or experimental jazz).

He acknowledges the economic issues posed by a fading jazz audience, but says that stations, rather than responding with creative programming, “innovated cost management practices.”

People seeking jazz on the radio still have many choices. As Johnson says: ”The postwar history of jazz radio has demonstrated that jazz is at a disadvantage on social networks that require or demand popularity. Still, jazz has dedicated fans who will seek it out wherever it is available, and it has adherents who will make it available to listeners…”

— Steve Provizer

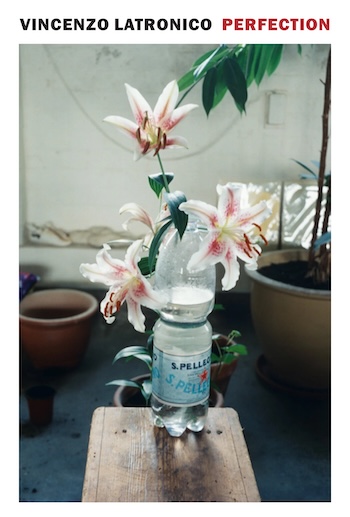

Revenge is a dish best served cold, but so is social satire, at least when it is pulled off with the proper deadpan touch. Why pick up an axe when a sharpened scalpel, wielded with diagnostic precision, can more effectively slice and dice layers of what can quickly be recognized as fragile illusions of bourgeois grandeur that many of us share. In this memorable novella, enough delusional fodder is cut off to reach the area that Emily Dickinson called “zero to the bone.” It is a devastating experience.

Revenge is a dish best served cold, but so is social satire, at least when it is pulled off with the proper deadpan touch. Why pick up an axe when a sharpened scalpel, wielded with diagnostic precision, can more effectively slice and dice layers of what can quickly be recognized as fragile illusions of bourgeois grandeur that many of us share. In this memorable novella, enough delusional fodder is cut off to reach the area that Emily Dickinson called “zero to the bone.” It is a devastating experience.

In Perfection (translated from the Italian by Sophie Hughes), Vincenzo Latronico dissects the beautifully banal lives of Tom and Anna, successful married freelance graphic designers in Berlin. At first, the young childless couple is self-satisfied to the point of smug urban exultance: they have a gorgeous apartment, ample salaries, chic friends, dine at the finest restaurants, and own the ‘perfect’ stylish processions. Maintaining a digitally-nurtured vision of freedom and fashionable comfort becomes a job in itself. And the determined pair pull it off, for a while. But, as the years go by, Tom and Anna find themselves stuck in a rut, exploited workaholics victimized by an economic system that’s built to instill and cultivate limited mental horizons. They are unable to see beyond the cushy conformity that’s being sold — around the globe — as the “desirable life”.

This meticulous portrait of sociological/psychological hollowness is brilliantly dramatized, though there are moments that the trap Tom and Anna have raced into is made plain.

“Now there were too many choices, with each one leading off on endless branches, preventing any real change. Their idea of a revolutionary future didn’t go beyond gender balance on corporate boards, electric cars, vegetarianism. Not only had Anna and Tom not had a chance to fight for a radically different world, but they couldn’t even imagine it.”

— Bill Marx

Jazz

Genres have been remixed and reinvented over the years. But the rhythmic allure of Latin Jazz has maintained its essential vitality since its full-scale emergence north of the border in the mid-20th century. Listening to it has always served to bring me out of my periodic focus on heady, chamber jazz and back to a more full-bodied appreciation of popular, dance-related styles, like mambo, cha-cha, and boléro.

Genres have been remixed and reinvented over the years. But the rhythmic allure of Latin Jazz has maintained its essential vitality since its full-scale emergence north of the border in the mid-20th century. Listening to it has always served to bring me out of my periodic focus on heady, chamber jazz and back to a more full-bodied appreciation of popular, dance-related styles, like mambo, cha-cha, and boléro.

Percussionist Poncho Sanchez (b. 1951) served an important apprenticeship in the band of the late, great vibraphonist Cal Tjader, an artist who knew how to make his music appeal to both cooled-out and heated-up tastes. Sanchez later gained a following of his own with a sound that never wandered too far from its sources in Afro-Caribbean music and post-WWII jazz. He has always kept things enthusiastically fresh. I had lost sight of him for a few years and was, therefore, doubly pleased to get word of a new release (his 31st!).

Poncho Sanchez & his Latin Jazz Band Live at the Belly Up Tavern puts the drums up front (conga, bongo, timbale, batá, and more) in an exuberant set of original and re-arranged pieces that highlight individual band members while keeping it very much a group effort. Leader Sanchez’s introductions and exhortations to the soloists bring the action up front. Ron Blake (trumpet), Francisco Torres (trombone), Andy Langham (piano), Tom Luer (saxophone), Ross Schodek (bass), Giancarlo Anderson (percussion), Jose Perez (timbale), and, of course, Sanchez (conga and vocals) all excel.

Sanchez’s vocals, embedded in a call & response with band members, are among the highlights of the lengthy “Batiri Cha Cha,” a showpiece that will make you wish you were a better dancer than you are (me, anyway). The Spanish lyrics of “Aunque Tu” inspire piquant solos from Torres and Langham. “Poncho’s Beat” succeeds at offering what we hear are “rhythms that will knock you off your feet.”

Trumper Blake references classic post-bop with “A Bientot,” a newly arranged Freddie Hubbard burner and “Night Dream,” his own breezy tune, which features three batá drums and evokes Wayne Shorter during his Blakey-to-Miles transition.

Some may quibble with the repetitive montuno piano figures behind the multiple percussion passages on the disc. But they are a minor (if at all, for you) distraction from what is a masterful set performed by a band led by a guy who knows how to communicate the fun and art that’s inextricably entwined in his Latin Jazz.

— Steve Feeney

Popular Music

More than any recent music, the British band Benefits’ Constant Noise captures the numbing effects of living under politicians and a media that retain their power by overwhelming us with messages of fear and anger. Following their 2023 debut album Nails, the duo has moved towards more accessible, even danceable music. While vocalist Kingsley Hall still shouts his way through several songs – “Divide,” where he trades verses with rapper Spakk, and “Live and Fear” – he’s now able to adopt a softer, more measured tone.

Nails felt like hardcore punk performed with a synthesizer and drum machine. Constant Noise cuts hardest when it turns down the volume, finding an eerie sadness amidst the many reasons to be pissed off. Even at their softest, Robbie Major’s keyboards are menacingly dissonant, as unsettling as the first scent of a raging wildfire on the horizon. Benefits demonstrate the potential of this approach softer approach best on “Missiles.” In its music video, Hall plays a self-satisfied man dancing onstage, ignoring the fact that “a man on the TV tells me missiles are firing.” A steadily buzzing synthesizer expresses a self-loathing that the song’s narrator might not recognize in himself.

Hall has an ear for the memorably cutting phrase, particularly internal rhymes: “the hypocritical hordes striking all the wrong chords,” “desert island dickheads who don’t give a damn.” “Land of the Tyrants” expresses the frustration of having to submit to oligarchs — guest singer Zera Tønin screams in exasperation. Built around organ, “Burnt Out Family Home” awakens memories of Spacemen 3’s strung-out hymns. Instead of just raging against the people they’re criticizing, Benefits are more inclined to inhabit their skin. Constant Noise’s last few songs try to find reasons for hope, though they sound exhausted.

— Steve Erickson

Anyone looking for the new Jim Kweskin album on Jalopy Records might want to know its proper title – The Berlin Hall Saturday Night Revue Presents Doing Things Right with Jim Kweskin. Yes, that’s a mouthful, but that’s fine because the record happens to contain a boatload of music, all of it comfortably settled in the folkie-jazzy-bluesy-old timey-good timey combination of genres that the singer-guitarist has been offering up since his long-ago days fronting Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band.

The largely laid-back disc features marvelously arranged and produced renditions of familiar tunes including “Show Me the Way to Go Home,” “Mona Lisa,” and “What’ll I Do,” as well as lesser-known numbers such as “Mardi Gras Mambo,” “Ducks Yas Yas,” and the album highlight “Viper Mad.”

Kweskin and his instrumental accompanists and guest singers handle it all with style and poise. Kweskin, who co-produced with Matthew Berlin, is in fine vocal fettle – slightly gruff yet somehow smooth – on the tragic but happy-sounding “Casey ’n Bill,” his gently rollicking take of “Mona Lisa,” and dueting with Samoa Wilson on the joyous marijuana song “Viper Mad.” That’s vocalist Matt Leavenworth kicking things off with some Western Swing on “Four or Five Times” and Racky Thomas, joined by a vocal chorus, on an easygoing rendering of “We’ll Meet Again.” A real treat is hearing the full-throated, brassy vocal by Annie Linders on the raucous and kinda raunchy “Ducks Yas Yas.”

Doing Things Right stands as an aural antidote for our troubled world. A breakdown of the program reveals there are nine tunes from the 1920s, two from the ’30s, one from the ’40s, and two from the ’50s. These are all songs that take you back to another time. There’s a New Orleans flavor zipping through much of it, but its success is due to the sound of innocence, and of the good old days that it conjures up.

Jim Kweskin and members of the Revue perform at Club Passim in Cambridge on April 8 at 8 p.m.

— Ed Symkus

Visual Arts

Edgar Degas’s Dancers With Fans, c. 1898. Photo: Wadsworth Atheneum

In introducing its current exhibition, Paper, Color, Line: European Master Drawings from the Wadsworth Atheneum, the museum uses words like “little known and often overlooked” and “hidden treasures” to describe its 1200 plus collection of European drawings. For most of its history, “it grew haphazardly, without a strategy for systematic growth.” About a third of the drawings were acquired since the collection was last shown in 1990. Many of the drawings in this European show have not been exhibited, the museum says, in decades. Others haven’t been shown at all

This selection, hung in roughly chronological order with thematic inflections, starts with the Renaissance and ends in the 20th century. The earlier sections lack most of the greatest names in European Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo draftsmanship: no Leonardo, Michelangelo, the Carracci, Fragonard, Reni, or Rembrandt. Some fine drawings by Rembrandt’s pupils— Govert Flinck, Nicolas Maes, Ferdinand Bols— stand in for the master himself. Still, there is a beautiful Guercino study of heads, which shows off his distinctive, energetic drawing style.

The show really begins to shine as it moves into the 19th century. There is a classic Ingres portrait drawing, the signature piece for the show, an engaging Courbet self-portrait, and a rich selection of French 19th-century artists—- Gericault, Delacroix, Degas, Cezanne, and more— as well as a few choice examples from the English school. For the 20th-century, the geography broadens out to include Grosz, Dix, Klee, Heckel, and others from Central Europe as well as a fine selection (as expected from the Wadsworth’s interests) of surrealism and costume designs from the Russian Ballet. Things thin out again towards the end of the century, but altogether a fine showing of some impressive works. A substantial catalogue accompanies the show.

— Peter Walsh

Oribe Round Plate, 2025, by Shigemasa Higashida, 16.14h x 16.14w x 4.13d in, Photo: courtesy of the artist

Master ceramicist Shigemasa Higashida (born 1955) takes his inspiration from what’s slightly imperfect in the environment. A master of glaze as well as form, his works (some of which are now on display at Concord’s Lucy Lacoste Gallery April 5 through May 3) are distinguished by their rich green Oribe glazes. The artist is also celebrated for his creative use of Shino, an esoteric glaze that morphs from a reddish brown into a white hue with bubbles. This glaze can trap carbon, which adds unusual visual effects to functional as well as experimental forms. Higashida also likes to use black and white for the sake of dramatic expressionistic statements.

Higashida’s pieces can remind the viewer of geographic layers on land and stone. These lush visuals of glaze suggest geometric planes and plateaus, seen in both closeup and from above. His tea bowls have been likened to canvases on which he projects, because of his deft and imaginative use of shading, out-of-this-world nature experiences. He relishes the exquisite conversation (perhaps dance?) that comes with combining clay and glazes.

Deeply committed to clay as an art medium, and focusing on showing contemporary, post WWII ceramic artists both established and emerging, the Lucy Lacoste Gallery was founded in 1990 with a focus on ceramics. The gallery elegantly showcases 20th and 21st century masters (like Higashida) as well as early career American and international ceramic artists. Besides exhibiting museum quality, cutting-edge pieces, the gallery also offers functional ceramic works by many well-known potters.

— Mark Favermann

Dance

A scene from Action at a Distance: Graveyards and Gardens. Photo: Robert Torres

Composer/violist Caroline Shaw once told an NPR interviewer that when she was a child, her personal place of worship was in front of her boombox radio: magically, and on demand, it emanated the classical music she adored.

For Action at a Distance: Graveyards and Gardens, an experimental duet conceived, created and performed by choreographer/dancer Vanessa Goodman and Shaw (presented by the Celebrity Series of Boston at Arrow Street Arts, Cambridge) – they call it a “performance installation” for dancer and musician – the collaborators ring the floor of the dimly lit stage space with table lamps and vintage tape decks, a record-player, and lots of snaking orange electrical cord. The domestic ambience, the feeling of being in a cozy cottage by the water, coexists with the detritus of a generation of archaic consumer electronics.

Two figures in sneakers and jumpsuits – Shaw in red over a long-sleeved dark tee and Goodman in green — rest contentedly until the audience settles. They could be workers or gardeners; they are certainly dressed for utility and effort.

And their work begins, riding on a shared impulse.

Shaw’s score is a melange of sweet humming and vocorder loops, sampled and distorted Bach harpsichord tinkling, an increasingly loud Pacific coast roar, and a viola alternately strummed like a ukulele and bowed with furious energy. When she adds a layer of text about the nature of soil and the micro-organisms that sustain it by Canadian agricultural scientist Derek Lynch, it’s hard to discern the details – the sound of the syllables seem more pertinent than the content, although I am pretty sure I caught the phrase “crevasses collect the brine of marinated memories.” There’s more than a whiff of Laurie Anderson in her “O Superman” period.

The meandering loops of Shaw’s score find their visual equivalents in dancer Goodman’s lanky body. Neutralized by the jumpsuit, Goodman’s motions have little directional orientation. Her arms erupt from the rectangle of her torso and then seem to wilt on the vine. When the ocean sounds grows louder, she evokes frilled masses of drifting sea-wrack; when she touches her body in fast pulses, she seems to transmit sudden sparks. She rubs a microphone along her clothes and smears dirt from a flowerpot along her arms. More and more, it seemed as if Goodman’s actions were generating Shaw’s score rather than being coincident with it.

Graveyards and Gardens is the kind of work that invites you to intuit the impromptu, playful creation that produced it. It’s an enigmatic work that could only have been created through a process of deep listening between two artists cultivating each other’s discoveries.

— Debra Cash

Tagged: "Action at a Distance: Graveyards and Gardens", "Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner", "Constant Noise", "Jazz Radio America", "Paper, "Phonetics On and On", "Poncho Sanchez & his Latin Jazz Band Live at the Belly Up Tavern", Benefits, Color, Horsegirl, Jim Kweskin, Line: European Master Drawings from the Wadsworth Atheneum", Poncho Sanchez, Ralph P. Locke, Steve Feeney, peter-Walsh

A thoughtful review elucidating a complex,

often puzzling duet. Although the connection between musician and dancer seemed to this

viewer difficult to understand, the reviewer’s

sensitive awareness of their intuitive connections

makes good sense.