Book Review: Clearing the Sill of the World — Thoughts on Ellen Wilbur’s Stories

By DeWitt Henry

With visionary daring, Ellen Wilbur leads us into unexpected corners, then transcends them profoundly and beyond expectation. Such stories are more than “moral fictions.” They are soul-shakers.

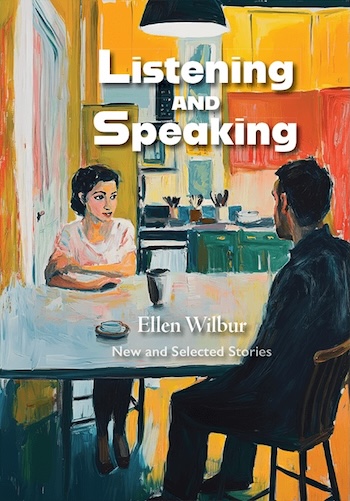

Ellen Wilbur’s Listening and Speaking: New and Selected Stories (Pierian Springs Press), her first collection since her widely praised Wind and Birds and Human Voices (1984), showcases 19 stories ranging from short-short, to short, to novella length. Most have appeared in prominent literary magazines over the past 40 years.

There is a beguiling oddness to Wilbur’s characters, whether they are old or young, male or female, married or single, articulate or silent, socially privileged or working class, worldly, reclusive, generous, or self-absorbed. Many live in Danville, a rural village, others in cities. They are haunted, fascinating, paranoid, doomed, sensitive in longing and anxiety; and often traumatized by their own and society’s wrongs.

Wilbur brings to mind Eudora Welty’s assertion that “a sheltered life can be a daring one” (see One Writer’s Beginnings). She brings Hawthorne’s and Kafka’s allegories to mind. She brings Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio to mind as well, both in his narrative strategies and his repressed “ordinary” grotesques. Her sentences are sometimes stilted, yet also lyrical in their grammatical, measured formality. Dreams figure prominently in many stories, while other stories seem dreamlike, gesturing oddly in surface action while suggesting drama in the author’s psyche. Her signature stories are dramas of spirit, vision, and faith.

In the opening story, “Rescue,” her narrator, like a recording angel, zooms in with voyeuristic curiosity on a “man and woman”— a postal worker and a florist — who drive to a seaside vista for a first kiss, but are interrupted by spotting a child drowning in the surf. The man runs to save him, but the woman hesitates and watches both child and man drown. The woman later blames herself, judged by a policeman, who had known her as “a fearless swimmer” in growing up. The conflict of spectatorship and responsible action mixes with something like a therapist’s awareness of the woman’s inner life.

This is followed by “The New Year,” where a male materialist, preoccupied with his city career, hears from family that his mother is dying. On his train ride home, he rehearses “all the good she did for him,” and in an impulse of magical thinking tries to divest himself of vanities, such as his costly tie, briefcase, watch, and wallet, vowing “I’ll give up everything, if only you’ll be alive to see me.” But this attempt at penance is taken to a deeper level as the train’s conductor stops him, returns his castaway possessions and understands: “It’s a terrible thing to lose your mother.” This encounter helps enough that, on the way into his mother’s hospital, the young man “moved forward on the sidewalk, inching towards the past.”

The theme of communion and compassion becomes an apologia for the writer throughout, beginning with “The Fortune Teller,” where a client who feels “scarred and ugly” is reassured by the medium that she is filled with kindness, will do much good in life, and her intellect “will flame.” In the story, omniscience becomes magically prophetic and intrusive: “I know too much for scorn. No one knows you better than I. Try to think of this.”

Writer Ellen Wilbur. Photo: courtesy of the artist

“Winter Scene” is a sketch told with a visionary ache. “A woman entered, and a burst of cold that whipped the kitchen air into a frenzy. The woman kicked the door shut with her toe. The table shuddered and the copper pot shook on the wall as she stomped across the floor, snow falling from her boots, carrying a grocery bag in each arm. She nearly dropped both heavy bags onto the table. ‘WHAH!’ was the sound she made as she released the bags.” We have no idea of the woman’s age or situation, but she is alone in this setting with its four chairs, and she proceeds, after several domestic actions, to cook dinner, yet suddenly is struck by a fatal heart attack. Meanwhile, “A man was speaking on the radio. Out in the yard it had begun to snow. Some jarring sound or unexpected sight made all the birds fly up together from the ground in a dark crowd, and in an instant they had disappeared from view.” We witness with the narrator our everyday rituals, which only appear to ignore mortality, and a nature of things that ignores or transcends who we think we are. The author’s vision is neither pitiless nor sentimental, but well-argued, genuine, and fully inhabited.

Wilbur is equally masterful with her most ambitious, long stories, both in first person. The first (“Storms and Wars”) is told by an autistic boy, who believes he has powers and whose OCD rituals seem to deflect natural disasters, cruelty, illness, and even death — a magical thinking that amounts to hallucination.

The second (“Wind and Birds and Human Voices”) centers on a traumatized World War II vet, Paul, who for decades has been confined to a VA hospital. Every summer, Paul hallucinates that he is in the midst of the Civil War, where he is pursued for his desertion by a merciless general and troops. Wilbur’s portrayal of Paul’s visions — indeed of mental illness itself — is comparable in drama and immediacy to that in Hannah Green’s I Never Promised You A Rose Garden or Katherine Ann Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider.

Later in Paul’s life, when he begins to improve, he befriends a fellow patient, Baron, who is worse off — bedridden, face bandaged, and unable to speak. One morning, forced by staff to have a physical exam, Paul refuses the visit. Meanwhile, Baron has gone off, alone, in a wheelchair to the the edge of a cliff, where he seems to intend to commit suicide. But Paul discovers his tracks and arrives in time to save Baron. He then rolls Baron into a nearby abandoned chapel, where he plays the organ expertly. Paul breaks into tears, at last acknowledging his memory of having deserted combat in Anzio and of shooting and killing a woman and child in a cottage doorway, having taken them for enemy soldiers. Still, while Baron plays, Paul sees “the pumping feet and the helpless legs which leapt and danced over the pedals.” He realizes that Baron isn’t real. Paul awakens back in the hospital, with a nurse and his mother at his bedside and is told “You’ve had a stroke You’ll be fine, but you can’t talk yet.” Seeing a tree branch out the window, Paul realizes that it is well into summer, time for his madness. But “the army was gone.”

With visionary daring, Wilbur leads us into unexpected corners, then transcends them profoundly and beyond expectation. Such stories are more than “moral fictions.” They are soul-shakers.

Note: Ellen Wilbur will be reading from Listening and Speaking: New and Selected Stories at Porter Square Books, Cambridge, on April 25 at 7 p.m.

DeWitt Henry’s recent books are Restless for Words; Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2023); a US edition of Foundlings: Found Poems From Prose (with art by Ruth K. Henry), Trim Reckonings: Poems, and Do I Dream or Wake? Longer Poems (all from Pierian Springs Press, 2024). He was the founding editor of Ploughshares and is Prof. Emeritus at Emerson College. Details at www.dewitthenry.com.