Classical Albums Reviews: Seong-Jin Cho and Jean-Efflam Bavouzet Play Ravel

By Jonathan Blumhofer

A pair of pleasant traversals of the French master’s complete piano music, or thereabout, from the still-relative-newcomer Seong-Jin Cho and the established Jean-Efflam Bavouzet.

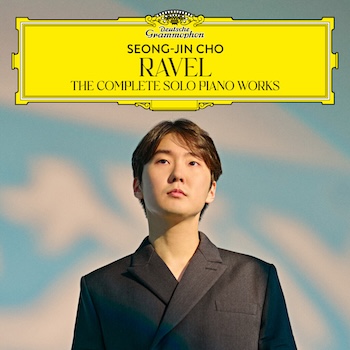

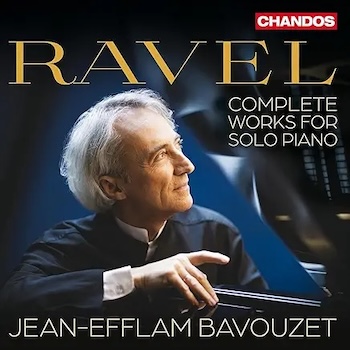

There’s nothing like a 150th birthday to jump-start the classical recording industry. And when the big day belongs to Maurice Ravel, the experience of wading through the offerings brings with it the prospect of being that much more pleasant. So it goes with a pair of traversals of the French master’s complete piano music, or thereabout, from the still-relative-newcomer Seong-Jin Cho (on Deutsche Grammophon) and the established Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (on Chandos).

There’s nothing like a 150th birthday to jump-start the classical recording industry. And when the big day belongs to Maurice Ravel, the experience of wading through the offerings brings with it the prospect of being that much more pleasant. So it goes with a pair of traversals of the French master’s complete piano music, or thereabout, from the still-relative-newcomer Seong-Jin Cho (on Deutsche Grammophon) and the established Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (on Chandos).

Cho, who’s all-Ravel tour landed in Boston in early February, is in many regards a natural Ravel pianist. His technique is impeccable and he’s got a wonderful command of his instrument’s color palette. When the stars align — as they do in Gaspard de la nuit’s “Scarbo,” with its astonishingly clean (and minimally pedaled) voicings, or the shapely “Menuet” from Le Tombeau de Couperin — the results are invigorating.

Problem is, that’s not consistently the story of the larger effort.

Not that anything is poorly done. Cho’s got all the notes in hand. The Menuet antique is clear, well-balanced, and conversational. Pavane pour une infante défunte is luminously voiced. Short selections like the reflective Menuet sur l’nom d’Haydn, chill À la manière de Borodin, and wistful À la manière de Chabrier come off winningly. So, too, the opening movement of the Sonatine and the whimsically flitting phrases of Miroirs’ “Noctuelles.”

At the same time, Cho’s Ravel lacks a certain degree of character and abandon.

True, the composer once offered that his music shouldn’t be interpreted, just played. But that doesn’t mean it should be refined to a fault. Yet that’s what happens in the too-polished Sérénade grotesque. Jeux d’eau, despite the emergent clarity of its various rhythmic layers, is, for phrasings and textures, somewhat stiff.

In Miroirs, “Une barque sur l’océan” needs more room to breathe. Similarly, “Alborada del gracioso,” for all the contrasts of tone and spirit that Cho mines from its pages, doesn’t exhibit the orchestral sweep that it might. Ditto for the Valses nobles et sentimentales, in which the pianist’s lovely-but-fussy performance simply gets lost within itself: only intermittently is one reminded that these waltzes are, in fact, a set of lilting dances.

Part of the album’s issues stem from its engineering, which places Cho’s Steinway too forward in the mix. As a result, there’s nowhere for the music to grow and develop, spatially. That’s especially evident in Tombeau’s concluding “Toccata,” which, here, is driven yet strangely lifeless. But the pianist’s tendency toward literalism — which was periodically on display in his Symphony Hall appearance (though less acutely than on disc) — suggests that, for all his considerable artistic strengths, Cho is still finding his interpretive footing in this fare.

The 62-year-old Bavouzet, on the other hand, is better established in this music and it shows. Like Cho’s, his playing is well-balanced and shapely. Rather differently, a sense of Gallic spirit infuses each of the older artist’s offerings.

The Sonatine, for instance, is both well-directed and strongly defined (by register, motive, and gesture), the blustery figurations in its closing “Animé” emerging with particular brilliance. In Menuet antique, Bavouzet’s pert enunciation of the music’s articulations and careful shaping of its dynamics — coupled with his tendency to lean into the beat a bit — results in a reading of uncommon freshness.

His approach to Miroirs is continually alive to Ravel’s nuanced scoring. The climactic swells of “Une barque,” the explosive apex of “Alborada,” and the haunting sonorities of “La vallée de cloches” all emerge viscerally. So do the limpid textures of Gaspard’s “Ondine.” There, too, the middle section of “Le Gibet,” with its intensely focused ppps, and the tempestuous runs of “Scarbo” are thrillingly dispatched.

Bavouzet’s take on Tombeau is likewise fresh, if a bit forceful in the “Rigaudon.” Nevertheless, the “Fugue” is nicely colored and the big dynamic range of “Forlane” is firmly articulated. Meantime, the French pianist’s Valses, with their splashy rhythms and bright, pointed dissonances, never loses sight of the music’s underlying, tripping impetus.

Neither does his reading of La Valse, a piece that, curiously, was omitted from Cho’s playlist. Maybe that was because the score was originally written for orchestra? Whatever the reasoning, Bavouzet’s stupendous account of the showpiece is a masterclass of virtuosity and feeling: who needs an orchestra when you’ve got a pianist like him on the bench?

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Chandos, Deutsche Grammophon, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet