Book Review: “The Last Tsar”– Last Train to Pskov

By Tom Connolly

Historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa’s towering achievement is to show that, while Nicholas II was betrayed, he lost his throne because he had made it impossible for anyone who loved Russia to be loyal to him.

The Last Tsar: The Abdication of Nicholas II and the Fall of the Romanovs by Tsuyoshi Hasegawa. Basic Books, 560 pp. $35

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, a professor emeritus of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara has devoted much of his career to upending commonly held convictions about the Russian Revolution. His definitive 1981 account of the February Revolution, which he substantially revised and updated in 2017, challenged much of the conventional thinking about that uprising. His book before The Last Tsar 2017’s Crime and Punishment in the Russian Revolution: Mob Justice and Police in Petrograd, was a street-level view of the Revolution. His latest work dramatizes the top-down collapse of the Russian monarchy with an almost hour-by-hour account of the final days of Nicholas II’s reign. It is a breathless narrative, building up considerable tension until the catastrophe arrives.

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, a professor emeritus of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara has devoted much of his career to upending commonly held convictions about the Russian Revolution. His definitive 1981 account of the February Revolution, which he substantially revised and updated in 2017, challenged much of the conventional thinking about that uprising. His book before The Last Tsar 2017’s Crime and Punishment in the Russian Revolution: Mob Justice and Police in Petrograd, was a street-level view of the Revolution. His latest work dramatizes the top-down collapse of the Russian monarchy with an almost hour-by-hour account of the final days of Nicholas II’s reign. It is a breathless narrative, building up considerable tension until the catastrophe arrives.

Forget Ten Days That Shook the World. If your knowledge of the Russian Revolution comes from John Reed’s book or the classic Eisenstein film, you have been misled. Even if you accept the story presented by Robert K. Massie’s bestseller, Nicholas and Alexandra, you have been misinformed. Hasegawa underlines the audacity of his version of events with this assertion: “Most of us presume this chain of events was practically inevitable; most of us are wrong.”

The core of this brilliant book is an almost hour-by-hour account of the nine days that brought down Nicholas II during the February Revolution. I have been obsessed with the Russian Revolution since 1967 when, as a child, I was fascinated by the media’s coverage of the 50th anniversary of the Revolution. Hasegawa’s study is a corrective to the mythology of the February Revolution, propagated not only by the popular press but by the Bolsheviks and their successors as well as later-day Marxist romanticizers and historians too eager to cut to the chase and get to Lenin’s arrival at the Finland Station.

Nicholas II’s reign is an historical tragedy, though there has been an effort, among many, to see the Tsar’s demise as almost mystically ordained. At his coronation, the gold chain of the Order of St. Andrew that he wore, symbolizing the Russian Empire, loosened from around his shoulders and fell to the floor. Later, festivities that were supposed to entertain the masses at the Khodynka field ended in disaster when bungled crowd control led to a stampede resulting in hundreds of casualties. Personally, Nicholas was profoundly fatalistic, never forgetting that he was born on the day of Job. When explaining his decisions, he often declared, “A Tsar’s heart is in God’s hands.”

Nicholas’s limited intellect and stubbornness proved to be a disastrous combination. Despite the omens and Nicholas’s failings, Hasegawa demonstrates that Nicholas need not have been the last tsar. The first third of the book races through Nicholas’s reign and the calamity of Russia’s experience in World War I to the final fateful International Women’s Day when the women of Petrograd took to the streets demanding bread in February 1917. Their cry of “хлеб” (khleb/bread) was the word that shook the world. Within hours, they shamed the men in the factories to go out on strike. When the Cossacks rode out to put down the protestors, the women goaded them to put down their whips. The Cossacks did so; soldiers shot their officers instead of the mob, and the government quickly collapsed. Hasegawa’s summary of Nicholas’s incompetence reveals that the government was already barely functional by then. What’s more, the weather was on the side of the Revolution. The authorities had raised the drawbridges over the Neva and the city’s canals to stop the crowds from reaching the centrum, but a sudden temperature drop froze the water, and the mobs easily crossed over.

While the revolutionary mobs engulfed his capital, Nicholas II spent his time at army headquarters, contemplating taking up dominoes again. The front was stabilized, and there was little for him to do besides take morning walks, enjoy meals with courtiers, and pore over maps revealing the static position of his armies. Ironically, Nicholas and his family’s attempts at patriotic service during the war had eroded the monarchy’s prestige. Alexandra and her daughters worked tirelessly as nurses, but they weren’t viewed as angels of mercy but were sneered at, viewed as “fallen women”. No doubt the scurrilous rumors about Rasputin’s intimacy with the Imperial Family helped generate this scorn.

Nicholas couldn’t do anything right. He walked every morning from his quarters to staff meetings, but his officers considered this a lapse, “a breach of military tradition for the supreme commander to come to the chief of staff’s office rather than the other way around.” The Tsar’s familiarity with his staff bred contempt. Yet an excited soldier, after the Tsar presented him with the St. George’s Cross, impulsively shook Nicholas’s hand, who was repulsed by the gesture. He immediately wiped his hand with a handkerchief in full view of the ranks.

Cocooned at army command, Nicholas ignored warning after warning from Petrograd. Hasegawa makes a strong case that had the Tsar agreed to Duma President Mikhail Rodzianko’s initial plea that he appoint “a ministry of confidence”, he would have kept his throne. Events moved quickly, and the Duma eventually demanded the Tsar accept a ministry “responsible to the Duma” that would have created a genuine parliamentary government. Nicholas rejected this as well. Yet it convinced him that the situation had deteriorated, and that he had to return to Petrograd. Or had it? Hasegawa argues that it was more likely that concern for his family motivated the decision to take the fateful train ride back to Tsarskoe Selo. His daughters had all come down with measles, and Alexandra feared an attack on the palace. Even she, who had previously admonished Nicholas to “give them the whip,” now advised giving in to the Duma’s demands. Hasegawa says that this paternal impulse doomed the Monarchy; tragically, it led Nicholas to the massacre in the Ekaterinburg cellar. The tortuous train ride back to his family meant losing contact with Petrograd, during which time any hope of reform died and abdication became the only option. Hasegawa’s focus on Nicholas’s fatherly solicitude is only one of the ways his narrative challenges conventional understandings.

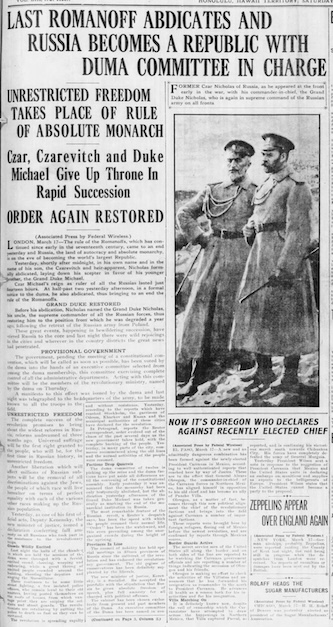

Newspaper headlines announce Nicholas II’s abdication as tsar. (The Pacific Commercial Advertiser, 03.17.1917)

Uncomfortable as it may be for many historians, Hasegawa insists that Nicholas, no matter his shortcomings, was betrayed. It was not quite a conspiracy, though every echelon in Russian society, even Nicholas’s cousins, schemed to overthrow Nicholas somehow and shut up Alexandra in a convent. The only part of the plot that was carried out was the assassination of Rasputin: which was done to save the Monarchy, but only hastened its collapse. After Nicholas abdicated, he made one of his only pointed diary entries: “Treachery, cowardice, and deception all around.” Hasegawa points to the “Judas kiss” General Ruzky planted on Nicholas when the Tsar agreed to give up the throne. Hasegawa is not being metaphorical; Ruzky was a major player in the abdication drama. He commanded the sector of the front where the events took place. Ruzky had done everything he could to ensure the Tsar was deposed, warning Nicholas of the bloodbath that would ensue should he try to put down the mobs by force, even interfering with the loyal units that had been dispatched to Petrograd to put down the rebellion and protect the Tsar’s family.

Hasegawa also highlights the role of General Alekseev, Chief of Staff of the Imperial Army, hitherto depicted as passively loyal. He decided that Nicholas’s incompetence endangered the war effort, and he had to be removed. Duma President Mikhail Rodzianko is revealed in The Last Czar to be much more ambitious and duplicitous than previously thought. While Nicholas was incommunicado on his train, Rodzianko contacted all of the front commanders in cooperation with General Alekseev and urged them to call for Nicholas’s abdication. He dreamed that the teenage heir, Alexis, would take the throne as a figurehead and Alekseev would serve as an all-powerful prime minister. He overplayed his hand, losing the confidence of the liberals and the Petrograd Soviet, which doomed any hope of a constitutional monarchy.

Most significantly, Nicholas’s generals reneged on their sacred oath of loyalty to him. Contrast this with Hitler’s generals, who, despite knowing the war was lost as early as 1943, refused to rebel because of their oath to the Fuhrer. The issue of honoring the oath to the Tsar versus loyalty to Mother Russia is at the center of Nicholas’s fall. The generals betrayed the Tsar because they believed he was the reason that Russia was losing the war. Hasegawa argues that the rise of a novel idea — country before sovereign — was the result of Nicholas’s framing of the war as a patriotic struggle and his inability to command loyalty. The wishy-washy liberals wanted something better than Nicholas. They sought some kind of regency under the auspices of a parliamentary system, but they vacillated over what form it would take. The generals wanted to defend their country, which called for a government that would enable victory. But, in the end, they had no better idea than Duma’s liberals about what form the new government should be.

Hasegawa incisively recounts the last hours of Nicholas’s reign, debunking the donnèes that dot previous accounts. Nicholas’s train was not rerouted because rebellious soldiers blocked the tracks; no eyewitness evidence can verify any such danger. Rather, it was the strange delusion of an elusive officer, Lieutenant Gerliakh, who decided on his own to report that the stations down the line from the imperial train were occupied by mutineers. There were no rebellious soldiers. Once the train was rerouted, it was out of reach of the telegraph, which meant that the Tsar lost contact with the capital. He wasn’t ignoring the rush of developments in Petrograd; Nicholas was completely cut off. Hasegawa contends that, if the Tsar hadn’t been stuck on the diverted train, he might have been able to save his throne: “Had Nicholas joined Alexandra in Tsarskoe Selo on March 1 instead of going to Pskov, it would have changed the course of the abdication drama drastically. The February Revolution’s outcome hinged on this mysterious Lieutenant Gerliakh, now lost in the murk of history.” This wild-card junior officer is key evidence in Hasegawa’s case against inevitability. Gerliakh’s false warning brought Nicholas to Pskov — that was the end of the line for the Tsar.

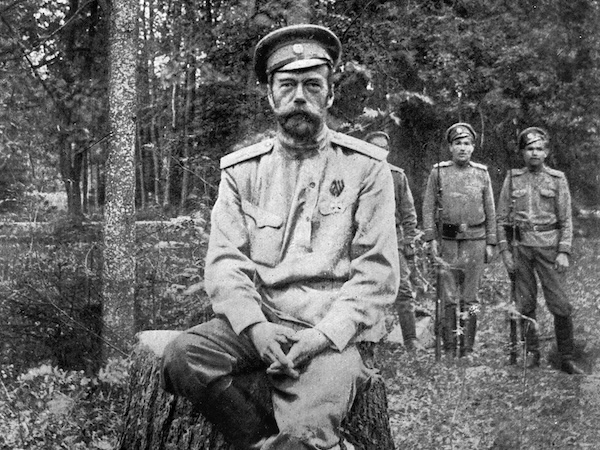

Nicholas II with guards outside the imperial palace. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Finally, none of the external forces bearing down on Nicholas, nor the circumstances of his isolation on the train, explains why Nicholas destroyed the Romanovs. His love for his family is what ensured its destruction. After telegrams from his generals convinced him to abdicate, Nicholas gave up the throne. But he then violated the Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire by signing away the rights of the lawful heir, his son Alexis. Nicholas named his brother, Mikhail, his successor. Why? Nicholas could not bear to be parted from his son, but Hasegawa also insists that he couldn’t stomach the thought of his son being brought up by his sister-in-law, whom he and Alexandra despised. Nicholas allowed his personal feelings to intervene in his succession decision — and that was fatal. Hasegawa explains, “Nicholas signaled to the world that the throne was a flimsy thing, a hand-me-down, easily discarded, and not a sacred duty born of an inviolable principle.” Nicholas had broken the law twice; he passed over the rightful heir and denied his son the throne.

Hasegawa recounts other bureaucratic details that made the continuation of the monarchy impossible. There were different drafts of the abdication document; one was signed by a witness in pencil. Worse, a Duma deputy backdated the timing of the Tsar’s abdication as well as the appointments of Prince Lvov as prime minister and Grand Duke Nicholas as supreme commander of the army. When these errors were revealed, they tarnished the legitimacy of the Provisional Government. Back in Petrograd, the astonished Duma leaders couldn’t fathom that the Tsar had abdicated in favor of his brother. No one rushed to inform Grand Duke Mikhail that he was to be Tsar; when he was finally summoned by the Duma, he had to dodge bullets on his way to the Tauride Palace, the seat of the aborning Provisional Government. Once there, Alexander Kerensky informed him the Duma could not guarantee his safety — the Grand Duke needed no further persuading to reject the crown. He did suggest that if the Constituent Assembly were to offer it, he would accept. Hasegawa theorizes that this veiled threat was a ploy by Kerensky to shatter any hope of maintaining the monarchy. The latter was one of the very few who had wanted to dispense with the Romanovs from the get-go. The generals and the Duma wanted to get rid of Nicholas, not the monarchy, but Hasegawa argues that their fecklessness led to unwanted consequences. The Tsar wanted to be an autocrat but did not know how to carry it off. The liberals wanted a constitution and a monarch but lacked the will to see their vision through.

Hasegawa’s achievement in The Last Tsar to show that, while Nicholas was betrayed, he lost his throne because he had made it impossible for anyone who loved Russia to be loyal to him. His incompetence was so encompassing it scuttled the institution of the monarchy. Worse, Nicholas’s incapacity made it impossible for any opposition to triumph against the Reds; any hints the Whites might be bringing back tsardom only rallied the Revolutionary forces. Nicholas’s failings made Lenin inevitable. As for the pertinence of this tragic farce to the machinations of the MAGA cult today — Hasegawa compares the followers of Rasputin to QANON true believers.

Tom Connolly is Professor of Humanities and Social Sciences at Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University. He recently edited a historical study (in English) of the 19th and 20th-century Jewish community of Döbling for the Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Institut für Kulturwissenschaften. His book Goodbye, Good Ol’ USA. What America Lost in World War II: The Movies, The Home Front and Postwar Culture is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin/PMU Press.