Book Review: “After Spaceship Earth” — Seriously Spaced-Out

By Trevor Fairbrother

In her stimulating book, Eva Díaz presents more than 30 conceptually minded artists who “reconsider how the applications of technologies used in near and outer space, once billed as progressive and exploratory, are today rife with negative effects such as resource depletion and privatization, economic inequality, and racial and gender domination.”

After Spaceship Earth: Art, Techno-utopia, and Other Science Fictions by Eva Díaz. Yale University Press, 256 pages, $55.

Eva Díaz is a professor at Pratt Institute, where she teaches courses on such topics as: art since the 1990s; the current season; and critical models in art and theory since 1965. The title of her new publication – After Spaceship Earth: Art, Techno-Utopia and Other Science Fictions — is sharp-witted and its jacket design is pitch-perfect. The cover photograph features an astronaut slumped on an obsolete seating unit in front of a derelict airport. Inside, the author focuses on a wide range of politically engaged artists from around the world who are addressing the space race begun in the Cold War era and the burgeoning “NewSpace” industrial revolution in which entrepreneurs compete to provide private spaceflight services.

Eva Díaz is a professor at Pratt Institute, where she teaches courses on such topics as: art since the 1990s; the current season; and critical models in art and theory since 1965. The title of her new publication – After Spaceship Earth: Art, Techno-Utopia and Other Science Fictions — is sharp-witted and its jacket design is pitch-perfect. The cover photograph features an astronaut slumped on an obsolete seating unit in front of a derelict airport. Inside, the author focuses on a wide range of politically engaged artists from around the world who are addressing the space race begun in the Cold War era and the burgeoning “NewSpace” industrial revolution in which entrepreneurs compete to provide private spaceflight services.

All the recent art presented in After Spaceship Earth is connected, if only subliminally, to R. Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983), the American inventor, architect, and catalyst for futurist theorizing. Fuller was one of the three innovative teachers that Díaz featured in her 2015 book, The Experimenters: Chance and Design at Black Mountain College; the others were Josef Albers (1888-1976) and John Cage (1912-1992). She argued that the experimental arts institution in rural North Carolina sharpened Fuller’s notion of “comprehensive design,” which was geared to his particular brand of “visionary, utopian romanticism.”

In her new book Díaz presents more than 30 conceptually minded artists who “reconsider how the applications of technologies used in near and outer space, once billed as progressive and exploratory, are today rife with negative effects such as resource depletion and privatization, economic inequality, and racial and gender domination.” She is devoted to explaining the historical and contextual underpinnings of the art she discusses, and I commend her equanimity in respecting Fuller’s experimentalism and integrity while advocating art that broaches his blind spots. There are 150 illustrations, mostly color, and they become increasingly eloquent as a pictorial ensemble as one progresses through the text.

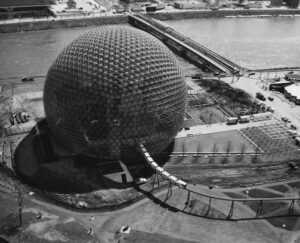

Aerial view of the United States Pavilion, Expo 67. Photo: Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal

The first part of the book, titled “Terrestrial,” focuses on the geodesic dome, Fuller’s most iconic project. The second part, titled “Extraplanetary,” analyses the metaphorical concept of “Spaceship Earth” — a term Fuller coined in 1951 but did not stress until the late Sixties, most famously in his influential short book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1969). Díaz’s kaleidoscopic stance is evident in this snippet from her acknowledgments: “And thanks of course to Bucky Fuller, Sun Ra, and George Clinton for their compelling weirdness that stimulated so many, including myself, to consider a different, better, more just world.”

Fuller was unusually accomplished: a brilliant designer, wed to pragmatic, less-is-more practices, and a natural self-promoter and charismatic showman. He flopped at Harvard, served in the U.S. Navy (1917-19), then focused on designs for mass-production, including housing and cars. In the early 1940s the military purchased his circular galvanized metal shelters that were easy to ship and assemble in war zones. Next, he developed the lighter and more graceful geodesic domes. Inspired by the lecture Fuller gave at the 1965 Conference on World Affairs in Denver, members of a Drop City, a counterculture artists’ community near Trinidad, Colorado, crafted their own idiosyncratic geodesic domes as homes and recreational spaces. Soon thereafter Fuller achieved world fame with the U.S. Pavilion for Montreal’s world fair Expo 67. Díaz rightly stresses the extraordinary fact that Fuller was “lauded by ‘straight’ culture and hippies alike.” Fuller’s writing could be long-winded and circuitous, but his concepts dovetailed perfectly with the hippie zeitgeist. The title of his 1969 book Utopia or Oblivion: The Prospects for Humanity underscored that affinity.

View of Drop City by Clark Richert, c. 1966. Photo: Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona.

At the beginning of her book Díaz notes her delight in finding several works that revisited Fuller’s dome designs in diverse projects around New York City in 2009. When she visited Nils Norman’s outdoor installation on Governor’s Island the motley array of pup tents in a weedy setting reminded her of “temporary refugee housing slowly calcifying into a permanent encampment.” Part of a series of site-specific projects sponsored by Creative Time, the work’s title — Temporarily Permanent Monument to the Occupation of Pseudo-Public Space — clearly invited an agitprop reading. When she visited Mary Mattingly’s Waterpod she encountered “several educational nodules that asked about alternatives for a sustainable local ecology.” Conceived as a six-month endeavor, Waterpod was a publicly accessible commune with two geodesic domes housed on a barge that traversed the city’s waterways. The residents were six artists who offered to host overnight visits for two guests. Dinners were keyed to the produce they grew and the chickens they kept on-board. The residents also gathered and treated rainwater for drinking, bathing, and cleaning; used solar and wind energy for power; and recycled or composted nearly all waste.

Fuller’s book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth likened the planet to a streamlined vehicular cabin that had no user manual and limited natural resources. He argued that the future of humanity depended on the creation of a plan to “save” the spaceship and instigate a new age of planetary stewardship. While Díaz celebrates Fuller as “an avid proponent of life in space,” she knows that his opinions have been moved in directions he could never have anticipated. Thus, she highlights the tech billionaires who are privatizing outer-space exploration and promoting space travel as a touristic experience for the privileged few. Díaz also acknowledges the unremitting dominion of patriarchy and white supremacy. She states, “Of the twelve individuals who have walked on the moon, all were men, and all of them white. Of all space travelers, less than 12 percent have been women.” A chapter titled “Ecofeminist World Building” discusses artists who investigate the interconnected arenas of “scientific exploration and colonialism, capitalist exploitation and sexism.” The individuals Díaz presents include Sylvie Fleury, Farhiya Jama, Aleksandra Mir, and Connie Samaras. In the case of Jama, a Somali-Canadian who envisions Black Muslim females in outer space, she draws attention to the affinity with Afrofuturist music in the 1960s and ’70s: “Sun Ra’s conjectures of travels to and from Saturn with the Arkestra … and George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic’s (P-Funk) concept of the ‘Mothership Connection.'” Jama’s work is a far cry from the elite touristic dreams fostered by Virgin Galactic, SpaceX and Blue Origin, companies funded by capital from the recent e-commerce and tech boom.

Mary Mattingly, Waterpod, 2009. New York City Harbor. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Yale University Press

I will end where I began, by returning to the cover of After Spaceship Earth. The astronaut photograph is a detail from The Airport, a 53-minute immersive video installation by the acclaimed Ghanaian-British artist John Akomfrah. The work, projected on three screens, centers on the remains of the international airport that served Athens until 2001. Akomfrah embarked on the project in 2015, when Greece was in economic crisis and experiencing an unprecedented increase in refugees arriving by sea. He clearly intended a dialog with Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film titled 2001: A Space Odyssey because the characters he presents include an astronaut and a gorilla. People attired in various 20th-century modes drift around the abandoned travel hub, paying no attention to the stranded astronaut (played by a Black actor). The Airport is a poetic and sad meditation on a liminal state where boundaries between past, present and future have dissolved. Díaz aptly repeats this comment that Akomfrah made in 2016: “The sense that there’s a place that you can go where you’re free from the shackles of history. The airport can stand for that because it’s a kind of embodiment of national — maybe even personal — ambition. The space where flight, or dreams, or betterment, can happen.”

Trevor Fairbrother is a curator and writer. In 1993 he and Kathryn Potts co-curated the exhibition and co-authored the catalogue In and Out of Place: Contemporary Art and the American Social Landscape at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. © 2025

I’m excited to read this new book about Bucky’s brilliant thinking. Steve Jobs called him the Leonardo da Vinci of the 20th century, because even decades after his death, most of us still don’t know what he was getting at. If anyone wants the basic primer on Bucky, and what he set out to do and why, here’s a book that does that, while appealing to young people and other reluctant readers.