Book Reviews: The Fiction of Mikołaj Grynberg — Simultaneously Embracing the Tragic and the Comic

By Roberta Silman

Two astonishing books about the lives of Polish Jews who survived the Second World War or were born after the war.

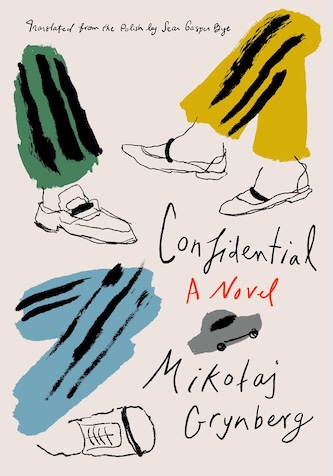

Two by Mikołaj Grynberg: I’d Like to Say Sorry, But There’s No One to Say Sorry To: Stories, The New Press, 2021, 137 pages, $19.99, and Confidential, A Novel, The New Press, 2025, 155 pages, $19.99. Both translated from the Polish by Sean Gasper Bye.

At the beginning of Sean Gasper Bye’s unusually eloquent Translator’s Note to the short story volume, he writes: “Mikołaj Grynberg’s work is not so much polyphonic as clamorous. It’s the sound of many voices pushing their way to the front, trying to be heard. This book’s Polish title, Rejwach, is a Polish Yiddishism meaning just this sort of cacophony, a holy racket deeply rooted in Jewish culture and history.” And although he is neither Polish nor Jewish, Bye understands, absolutely, what Grynberg is doing. He has given us wonderful translations of these two astonishing books.

At the beginning of Sean Gasper Bye’s unusually eloquent Translator’s Note to the short story volume, he writes: “Mikołaj Grynberg’s work is not so much polyphonic as clamorous. It’s the sound of many voices pushing their way to the front, trying to be heard. This book’s Polish title, Rejwach, is a Polish Yiddishism meaning just this sort of cacophony, a holy racket deeply rooted in Jewish culture and history.” And although he is neither Polish nor Jewish, Bye understands, absolutely, what Grynberg is doing. He has given us wonderful translations of these two astonishing books.

Grynberg is Jewish, was born in 1966 in Poland, and still lives there. He identifies himself as a photographer, but he is also a psychologist, a collector of oral histories that have been published in four nonfiction books, and, now, with these two books, a first-class fiction writer. His prose, as translated here, pulses with life, and many of his subjects are Polish Jews who survived the Second World War or were born after the war.

Most of us know that in the 1930s Poland had the largest Jewish population of any country in the world — roughly three and a half million. At the end of the war, there were myriad stories of displaced Jews going “home” only to find that they were far from welcome. Influenced by those tales, I never realized that there were Jews living in those countries overrun by the Nazis in the middle of the 20th century. Then, in 2011, I accompanied my structural engineer husband, Robert Silman, on a trip authorized by the World Monuments Fund to investigate some of the “ruined synagogues” in Lithuania, as well as the leaking roof of the Great Synagogue of Vilna. At that time there were five thousand Jews in Lithuania, most of them young, the grandchildren of Jews who had fled east to China toward the end of the war when going west was simply not possible. At this point, that number seems to have declined. Depending on how you define the word “Jew,” the Jewish population of Poland in 2025 seems to be between 15,000 and 25,000 in a country that has a population of roughly 3.8 million. And now those Jews, as well as their gentile neighbors, have a voice in these short but powerful works by Grynberg.

There are 31 short stories in I’d Like to Say Sorry, But There’s No One to Say Sorry To, which was published in the United States in 2021. They are more like dramatic monologues, sometimes in the first person, sometimes in the second person addressing You, the listener. They evoke what it’s like to live in Poland today while somehow coming to terms with its tragic past. We meet people who have passed as Christians but were born Jews, people who need to divulge the truth before they die, kids who visit Catholic Grandma only to be sent to a “Jewish camp” to find their roots, tourist guides, teachers, survivors who were hidden in both homes and convents, and kids who are currently victims of a kind of inherited antisemitism, gentiles who feel assaulted when visited by descendants of Jews that they helped. It is a wide range, and always lurking beneath the tales are the memories of the Holocaust, the deep need for connection that inhabits both gentile and Jew, and the penchant for humor that makes survival, then or now, bearable.

There are 31 short stories in I’d Like to Say Sorry, But There’s No One to Say Sorry To, which was published in the United States in 2021. They are more like dramatic monologues, sometimes in the first person, sometimes in the second person addressing You, the listener. They evoke what it’s like to live in Poland today while somehow coming to terms with its tragic past. We meet people who have passed as Christians but were born Jews, people who need to divulge the truth before they die, kids who visit Catholic Grandma only to be sent to a “Jewish camp” to find their roots, tourist guides, teachers, survivors who were hidden in both homes and convents, and kids who are currently victims of a kind of inherited antisemitism, gentiles who feel assaulted when visited by descendants of Jews that they helped. It is a wide range, and always lurking beneath the tales are the memories of the Holocaust, the deep need for connection that inhabits both gentile and Jew, and the penchant for humor that makes survival, then or now, bearable.

Confidential, which has just been published this past January, is a jigsaw of a novel, with 27 chapters, all with intriguing titles, written in the third person about three generations of a Polish Jewish family who have no names. They are referred to as Grandfather, Father, Mom, Son, etc. I must confess that I always find this approach a bit unnerving and I did here, as well. Yet, as I got to know the characters, I was not as bothered by this device. And as I read about their often strange adventures — for example, the Mother needing to go to funerals to see if she can cry, the physicist Son afraid to go to Germany for professional conferences — I was reminded of the work of an old favorite, Isaac Babel. In both Grynberg and Babel there is not only a Jewish presence but an aura of what has been called Yiddishkeit, for want of a better term, which embraces the tragic and comic simultaneously.

In the end, it is the tragic which resonates more sharply. These are people who have been “steamrolled by history,” whose lives give new meaning to the notion of “home,” and whose traumatic memories — both individual and collective — force them to lead lives so quirky that the word eccentric barely scratches the surface. Their dialogue cuts to the bone, they tumble through their lives at what sometimes seems a breakneck pace, sometimes a slow crawl, and yet they continue to live. Survival seems to be the primary goal, despite all the obstacles that stand in the way of their living a more stable, what we would call a more “normal” existence. Indeed, normal does not seem to be the point. In the chapter called “Happiness,” where the Son is being nagged on the phone by an old gentile school friend who wants to see him, there is this apt observation:

“I’ll tell you why I’m really calling.”

There are two possibilities, he thought, either your family killed Jews or saved them. Too late for me to be fussy, you’ll tell me anyway.

Here is how the author and Bye responded to a question at a Jewish Book Council gathering about Grynberg’s need to write from the “inside” of his characters:

Each of us lives in their own reality, and none of them is one-dimensional. Indeed, I live in a country that still defines itself as Catholic, although careful observation of current trends will soon force us to reckon with this opinion.

I have no doubt that a place outside the majority is far more interesting for a writer.

And I have no doubt that Grynberg will continue to do the work he does so well. His courage and talent are exemplary. But I must confess that the vignette that sticks in my mind is from the stories, entitled, “The Convent” and goes roughly like this:

My mother found shelter in a convent. She was kept there and that allowed her to survive the war…. She was eleven and never saw her family again….

Mom left the convent as a Roman Catholic…. She was fifteen…. There was no one waiting for her outside the gates.

She went to her family home, but a new family was living there now. She wandered. She turned down the emissaries who wanted to take her to the State of Israel, which was just then being born. She met a man who remembered her parents. She married him in a Catholic ceremony — she was Catholic after all….

I was born in 1954. At that time, we were living a few doors down from where my mom’s parents had lived. Until 1968 I knew nothing about them. The word “Jew” was never spoken once in our home. When one of our neighbors said to my mother, “Get the hell out of here, you rotten kike, go to Israel,” I froze with fear but also amazement.

At home we held a brief huddle. The idea that won out was one that to this day I can’t understand. Dad thought of it, and Mom agreed. I was sent to a convent, because “when bad times are coming, we hide Jews behind walls.”…

Permit me to sum up my story.

I thank the convent for sheltering my mother during the war. I hate the convent for what I went through there. I didn’t speak to my father for the rest of his life and I’m trying to understand my mother to this day. Once I realized that there are countries where being Jewish isn’t the only point of reference, I left Poland. I didn’t want my children to end up in a convent.

It isn’t usual for me or any reviewer to be rendered speechless.

But here we are.

Roberta Silman is the author of five novels, two short story collections, and two children’s books. Her second collection of stories, called Heart-work, was just published. Her most recent novels, Secrets and Shadows and Summer Lightning, are available on Amazon in paperback and ebook and as audio books from Alison Larkin Presents. Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review) is in its second printing and was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for The New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com, and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.