Doc Talk: “Chaos” Reigns

By Peter Keough

Errol Morris takes another look at Helter Skelter and the Charles Manson murders.

Chaos: The Manson Murders. Directed by Errol Morris. Based on the book by Tom O’Neill and Dan Piepenbring. On Netflix.

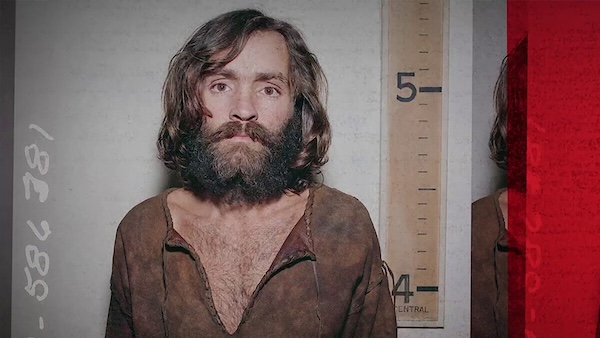

A scene from Errol Morris’s CHAOS: The Manson Murders.

Sadly, it’s almost refreshing to watch a documentary about a murderous cult that isn’t the one currently running our country.

Perhaps, after his previous film Separation, which examined the draconian border policies of the previous Trump administration now gleefully resumed in the sequel, Errol Morris might have regarded such a reinvestigation of one of the most sensational crimes of the 20th century as a less harrowing, near nostalgic change of pace. But the subject’s relevance to the present state of affairs, though not directly stated, becomes painfully clear.

As is well known, on the night of August 8-9, 1969, four acolytes of Charles Manson brutally murdered actress Sharon Tate, the pregnant wife of Roman Polanski, in her home in the Hollywood Hills. The next day they invaded a seemingly random nearby residence and killed the two occupants, husband and wife Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. Months later, Manson and cult members Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Leslie Van Houten were arrested, charged, and convicted in a trial headed by L.A. prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi (the fourth perpetrator, Tex Watson, was convicted in a separate trial).

Bugliosi’s 1974 book about the crimes, Helter Skelter, has sold more than seven million copies and his version of the events has endured as the dominant narrative. The motive for the crime, according to him, was Manson’s mad plan to instigate a race war – called “Helter Skelter,” after the Beatles song — from which he and his band of anarchic druggies, hippies, petty criminals, and underage sex slaves would somehow emerge the ultimate beneficiaries.

It’s a scenario entertainment journalist Tom O’Neill had also pretty much accepted when he took an assignment in 1999 by the now defunct Premier magazine to write a story about the state of Hollywood on the 30th anniversary of the murders. That story never got written, but despite O’Neill’s initial lack of enthusiasm for the topic, his investigation took him down a rabbit hole of revelations and possible conspiracies. It obsessed him for years, with questions lingering even after he published CHAOS: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties, his 2019 book about his findings.

As indicated by the title, Morris’s film draws heavily on O’Neill’s book and the author is his chief interview subject. Though Morris touches on other topics, O’Neill raises the dominant theme at the very start. “One of the biggest mysteries of this case,” he says, “is how Manson was able to gain control of his followers to the degree that he could get them to go out there and kill on command — without remorse, without hesitation — complete strangers.”

Cue a clip from The Manchurian Candidate (1962) in which an American POW captured during the Korean War complies with the order of a Chinese general to blow out the brains of a fellow GI.

In this case, though, it seems the brainwashing techniques were not North Korean in origin but home-grown. Morris and O’Neill trace connections between Manson and the FBI’s COINTELPRO and the CIA’s CHAOS projects — covert, extralegal assaults against left wing, student, and civil rights activists and militants in the ’60s and ’70s. In particular, he singles out the near-mythical MKUltra program, which experimented with LSD and other mind-altering methods to condition operatives to become robotic assassins.

As with the Kennedy assassination, the problem with investigating these theories is that most of the principals involved are dead. Among those still alive are Bobby Beausoleil, who is serving life in prison, not for the Tate-LaBianca massacre but for murdering, at Manson’s behest, the musician Gary Hinman.

Beausoleil is dismissive of some of O’Neill’s speculation. “There’s no doubt in my mind what the motivation was,” he says in a phone call to Morris from prison. “Charlie had gotten paranoid of his own people. He wanted to bind them to him through their committing bad crimes.” Maybe so, but aside from the fact that Beausoleil might not be a model of veracity, that doesn’t explain why Manson’s followers obeyed him.

Throughout Morris’s tone remains sardonic, almost playful, and sometimes macabre. The editing is abrupt, jarring, with inserts of staticky text and graphics evoking tabloid newspapers — or Tabloid, his larkish 2010 documentary about a sensationalized ’70s kidnapping case. At one point during an interview about the discovery of Beausoleil’s murder victim, he says off camera, “I read somewhere that they could hear the maggots eating him.” His words are accompanied by an extreme close-up of munching worms. The interviews with O’Neill are often shown in jazzy split screens from two different angles, perhaps to suggest that there might be another side to this story. He includes a generous dose of Manson’s music, enough to convince you that L.A. producer Terry Melcher, a key figure in the case, had good reason not to give him a recording contract. And a recurring motif is a tableau of Manson as a puppeteer holding the strings of his murderous minions. But Manson is also a puppet, and we don’t see who’s holding his strings.

Bleak stuff, but handled with a light touch. Morris’s dark capriciousness doesn’t undermine the gravity of the material but underscores its horror. It also suggests its relevance to today, begging the question of how some 77 million people voted for a candidate despite knowing full well that he would unleash chaos beyond Manson’s wildest dreams.

Meanwhile, Morris is in the process of making a film about Ukraine. The tentative title: Betrayal.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).