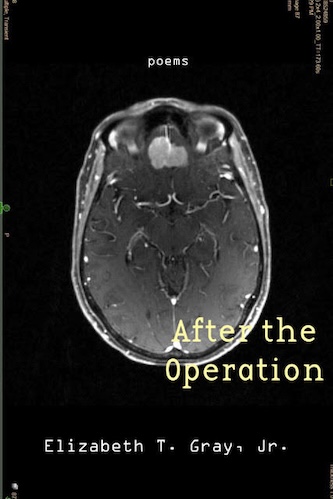

Poetry Review: Songs from a Bone Window — Elizabeth T. Gray Jr.’s “After the Operation”

By Michael Londra

For poet Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., the neurological is also archeological.

After the Operation by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., Four Way Books, 65pp, $17.95

Rimbaud’s aphorism “I is an Other” articulated a vision of the self as unfamiliar and irrational, split from within by unresolvable psychological contradictions. It subverted the dominant nineteenth century Cartesian belief that the intellect was a transparent and logical unity. Rimbaud believed poetry was a privileged mode for unearthing enigmatic truths because it tapped into the estranged part of the self. In this way, Rimbaud anticipated Freud’s psychoanalytic interpretation of subjectivity as fractured into conscious and unconscious components. Dreams for Freud were truth-texts built from images that, when articulated in language, worked in the same way as poetry — the unconscious is structured like a poem. Given that the mind is ‘hosted’ in the brain, what connections are there between neural networks and Rimbaud’s unconscious otherness? In other words, what happens to poetry if it is threatened by a cerebral tumor? If the internal barrier between I and Other is dissolved, and the borderlines between the anarchic and the conscious self are erased, what are the implications for personhood and for poetry?

Rimbaud’s aphorism “I is an Other” articulated a vision of the self as unfamiliar and irrational, split from within by unresolvable psychological contradictions. It subverted the dominant nineteenth century Cartesian belief that the intellect was a transparent and logical unity. Rimbaud believed poetry was a privileged mode for unearthing enigmatic truths because it tapped into the estranged part of the self. In this way, Rimbaud anticipated Freud’s psychoanalytic interpretation of subjectivity as fractured into conscious and unconscious components. Dreams for Freud were truth-texts built from images that, when articulated in language, worked in the same way as poetry — the unconscious is structured like a poem. Given that the mind is ‘hosted’ in the brain, what connections are there between neural networks and Rimbaud’s unconscious otherness? In other words, what happens to poetry if it is threatened by a cerebral tumor? If the internal barrier between I and Other is dissolved, and the borderlines between the anarchic and the conscious self are erased, what are the implications for personhood and for poetry?

One answer can be found in Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr.’s latest collection of poetry, After the Operation. In this book, she chronicles her experience of brain surgery: the initial diagnosis, the eight-hour procedure entailing the use of a saw to cut directly into her skull in order to extract the benign tumor, and the twelve months of recovery that followed. Creative writing prompts are routinely advised, as a therapeutic exercise, to patients like Gray, who have endured complex invasive surgery. The idea is that organizing traumatic experience into a narrative will accelerate the healing process. While poetry as therapy surely played a role in Gray’s recovery, After the Operation yearns to elevate rehabilitation into art. She goes about accumulating dreamlike fragments into a nest of images with the goal of doing more than telling a story or alleviating suffering. In fact, Gray draws on her skills as a translator in this volume. Finalist for the 2023 PEN Prize for Poetry in Translation for her renderings of influential Iranian poet and filmmaker Forugh Farrokhzad, Gray acts as her own interpreter, translating the foreign tongue of her hallucinatory voyage to the Other side of consciousness — and back — into verse that records what was lost during the trip and what remains.

Via a brief introductory note, poet and neurologist Dawn McGwire cites “I is an Other” established the context for what is to come: “These poems brilliantly enact Rimbaud’s meme ‘Je est un autre’…The other is a brain tumor, growing in her falx, a curved blade of tissue that partitions the two hemispheres; the tumor that divides her.” Harvesting material from personal medical records and journal entries, as well as bringing in the voices of family, friends, and doctors, After the Operation is driven by a hybrid choral approach that experiments with form and grammatical relationships: the poet places parentheses at either end of certain poems to evoke incomplete links between thought and expression. Gray evokes catastrophe by frequently speaking through first person plural “we” and third person “her,” simulating the feeling of being an-other to oneself: “After the operation her mind / became an uninhabited coast…all shatter / and thoroughfare.”

By leaving her poems conspicuously untitled, Gray also underlines the sensation of radical alienation, an eerie embrace of absence that signified psychological trauma. Despite the successful removal of the entire tumor, her fear of the extent of the damage that might have been done to her mental acuity is conveyed with stark alarm:

(After the operation,

intact abandoned its nouns, the idea

itself fell

apart and was

last seen somewhere

in an enamel

bowl in pieces

next to a bone saw)

Gray parses medical jargon through a poetic lens: “(They tell me it will be a partial pterional resection…What does this mean. / The pterion…The weakest part of the skull. / From pteron, meaning wing or feather. / The precise location where trickster Hermes’s wings were. / There will be what they call a bone window. And then titanium.)”

Elizabeth T. Gray Jr. Photo: courtesy of the artist

“[B]one window” is a phrase that haunts these poems, a reflection of the isolation, despair, perplexity, anguish, and helplessness that suffused Gray’s struggle to make verbal music. After the Operation reads like a book of arias made to be sung from a bone window. For example, there’s Gray’s sequence of “Thirty Vanished Scents,” which pounds out an object-laden blues that is determined to (eventually) swing in praise of life. The series begins with “garbage, seaweed, dung fires, perfume, musk, garlic, whiskey, bacon, woodsmoke, old books, Chennai, grasses, dog, horse, bird, her husband, cider, pears, low tide, cedar, oranges, eucalyptus, pepper, thyme, onion, a storm at sea, dry leaves, cherry blossoms, roses, clove” and moves onto “Ten Olfactory Hallucinations…hot metal, vitamins, the future, betrayal, sulfur, counterfactuals, intentions, departure, cognition, flight.”

For Gray, the neurological is also archeological. One of her prose poems interlaces Howard Carter’s journals of excavating Tutankhamen’s tomb with her surgeon’s narrative of the operation. The logic of poetry: tomb robbing melded with brain surgery. The tumor is a (negative) treasure to be plundered: “Under the lobular overhang, the tumor was of yellow crystalline sandstone, slightly tinted, having…four goddesses…in gold at each corner protecting it.” Gray’s skull and Tut’s burial chamber are sacred temples, structures intended to remain sacrosanct. A holy seal has been breached. There will be consequences.

A year of restorative post-op rehab later, Gray still “fretted about the tumor / Where was it…Did it remember her?” That evil object may linger in her memory, but After the Operation sublimates the nightmare in a powerful aesthetic structure. The wall between the I and Other is restored through poetic articulation, a confidence in the power of metaphor and imagination. Trust in poetry. At any moment, even from a bone window, it is possible to take flight:

(After the operation, there were birds

Birds you could see, birds you couldn’t …

feathers: warmth offered

from beneath a wing …

As things settle and other parts go silent

the feathers become easier to hear)

Michael Londra’s fiction, poetry, and reviews have appeared in Restless Messengers, Asian Review of Books, and The Fortnightly Review, among many others. He contributed six essays and the introduction to New Studies in Delmore Schwartz, coming soon from MadHat Press; and is the author of forthcoming Delmore&Lou: A Novel of Delmore Schwartz and Lou Reed. He lives in Manhattan.

Tagged: "After the Operation", Elizabeth T. Gray Jr., Four Way Books