Visual Arts Review: A Fruitful Exchange — “Believers: Artists and the Shakers”

By Lauren Kaufmann

The exchange proved to be as fruitful for the artists as it was for the Shakers.

Believers: Artists and the Shakers, Institute of Contemporary Art, on view until August 3

Wolfgang Tillmans, Shaker Rainbow, 1998. Courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, Hong Kong and New York; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin and Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

An exhibition inspired by a Shaker community in Maine would seem to be an unlikely choice for the ICA/Boston. But Believers: Artists and the Shakers comes with a fascinating backstory. In 1998, the ICA mounted The Quiet in the Land, an exploration of a shared experience between 10 artists and the Shaker community at Sabbathday Lake, Maine. ICA director Jill Medvedow welcomed the artwork to the museum, and now, on the cusp of her retirement, the museum revisits the original show, while expanding on the work included in the first exhibition.

In 1996, independent curator France Morin conceived the idea of bringing 10 artists, for a summertime residency, to the Shaker community in Sabbathday Lake, Maine. Initially, the Shakers were reluctant to agree to Morin’s proposal, but they eventually consented to house the artists. They stipulated that the artists had to participate in morning chores and assist with community projects. The artists fed the sheep, mowed the grass, and rebuilt the fence in front of the meetinghouse. In the afternoons, the artists were free to work on their art. They also prepared dinner one night a week. According to the video on the ICA website, the Shakers were delighted to try the new dishes.

The exchange proved to be as fruitful for the artists as it was for the Shakers. While the artists found inspiration in the simplicity and spirituality of the community, the Shakers grew to appreciate the talents and newfound friendship of the artists. Curator France Morin noted in the video that the residency was intended to give back to the Shakers. The exhibition offered ample proof that the artists had achieved that goal.

To understand the Shaker lifestyle, it helps to consider their history and their underlying religious philosophy. The Shakers are a Quaker sect that started in England in the mid-1700s. They are well known for their unusual worship services, in which they danced while praying, a ritual that inspired the name “shaking Quakers.” In addition to their unorthodox manner of prayer, Shakers were famous for their furniture, with its simple lines, clean design, and fine craftsmanship. Shakers invented the clothespin and the circular saw.

In 1774, Ann Lee led the first group of Shakers to the US, where they settled in upstate New York. Believing that the second coming of Christ was imminent, the Shakers embraced gender and racial equality. Because they do not proselytize and they lead celibate lives, the Shaker movement is dying out.

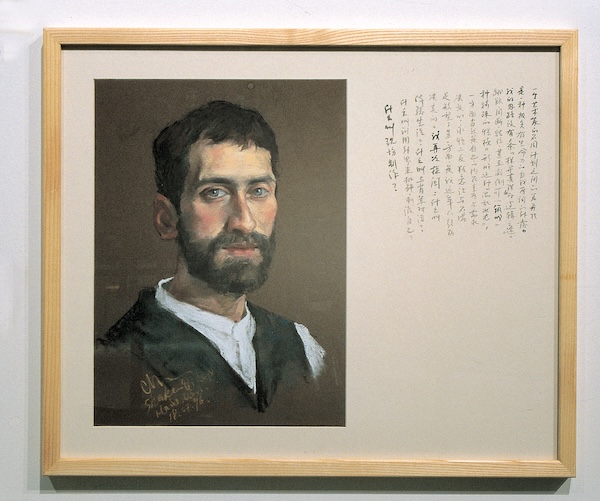

Chen Zhen, My Diary in Shaker Village, 1996-1997. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Continua

Believers: Artists and the Shakers combines some of the pieces that were featured in The Quiet in the Land with a number of new works. When you enter the exhibition space, you encounter a video that was shot in the summer of 1996 by Janine Antoni. Holding her camera while spinning in circles, Antoni captures the rapturous spiritual experience of Shaker prayer. Antoni filmed the video inside of the Shaker meetinghouse at Sabbathday Lake.

Adjacent to Antoni’s video is the installation of a new work by Jonathan Berger. This text-based sculpture is a transcript of a conversation with Brother Arnold Hadd, who spoke about “nameless love,” a term for nonromantic love. The text addresses the Shaker belief that labor is a spiritual expression of divine love. Berger has used tin to create the text, which is suspended from the ceiling, with two openings on either side, symbolic of the separation of men and women. Unfortunately, because the text sculpture has not been given a solid backing, it is difficult to read. I asked a Visitor Assistant about the readability issue, and she agreed that it was problematic. She suggested that it would be helpful for the curator to provide a transcript, so that museum visitors could read the words. (Since my visit, the museum has produced a transcript of the text.)

My conversation with the Visitor Assistant was easy, warm, and helpful. The ICA has adopted a visitor engagement model that enhances the museum experience in a meaningful way. Instead of using uniformed guards who fade into the background (and only engage with visitors when they get too close to an object or work of art), the ICA employs knowledgeable staff members who roam through the galleries and are available to answer questions and provide insight into the exhibitions.

Kazumi Tanaka, Communion, 1996. Courtesy of the artist

The same Visitor Assistant whom I approached about Berger’s text sculpture also shared some details about the work of Kazumi Tanaka, who participated in the Sabbathday Lake residency. Tanaka’s earlier version of Communion was made up of two wooden tables, each with six plates floating over water. The furniture symbolizes the separate tables where Shaker men and women eat their meals. In the current exhibition, Tanaka presents two tables, but this time, with just one plate per table. The Visitor Assistant explained that the two plates stand for the remaining two Shakers in the community. I was grateful to learn that fact, but I wondered why that important detail didn’t make it into the wall text. I think other museum visitors would be interested to know that, too.

For the original exhibition, Tanaka also conceived a piece that evoked an open door, but it didn’t make it into the first show. The door represents Ann Lee’s belief that the creed’s trusting members should open the windows and doors to anyone who comes. In this revisit, the piece seems especially fitting because the Shakers opened their doors wide to the 10 artists who participated in the 1996 residency.

Photographer Wolfgang Tillmans shares 140 unframed photos, all from the 1998 exhibition. During his residency, he documented snippets of everyday life. There are photos of the buildings where the Shakers lived and worked, shots of them and the artists completing tasks, and images of the local landscape. Tillmans notes that “the installation is an expression of my piecing together at the time an understanding of how life, art, architecture, nature, and animals, as well as religion and spirituality, are all part of a simultaneity of human experience, through the lens of my very specific movements and experience of the world.”

Nari Ward, Community Threshold, 1997/2024. Courtesy the artist; Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London; and Galleria Continua

In Community Threshold, a found object sculpture, Nari Ward updates the work that he created for the original exhibition. Ward took the parts that remained and embellished them with children’s cots, bed springs, and lecterns. He applied strips of burlap that suggest traditional Shaker basket making. He’s embedded two wash basins with mirrors that he scattered with soil that he recently gathered from Sabbathday Lake. Ward’s decision to amplify his earlier work underlines the enduring impact of his residency.

Chen Zhen made a drawing every day of his stay, and My Diary in a Shaker Village consists of 27 drawings and photographs. Portraits of the Shakers are interspersed with drawings of baskets, Buddhas, and Chinese calligraphy. Because the grouping of framed drawings is hung closely together, the assemblage makes a powerful impression. You sense that Zhen’s diary represents a physical manifestation of the internal enlightenment provided by Sabbathday Lake. In a page taken from his diary, Zhen compares his time with the Shakers to a three-month stay in Tibet. He reflects on the role of the diary, observing that keeping it reminded him of a Buddhist saying, “Living means the experience of one day after another.”

Although Taylor Davis didn’t participate in the 1996 residency, he recently visited Sabbathday Lake, where he spent time with Brother Arnold Hadd. For All Thy Mercies is a large-scale trapezoidal collage that blends iconic images from Shaker life, such as a ladderback chair and bentwood boxes, with pictures from everyday rural life, as well as those that relate to stewardship, a central component of Shaker life. These images are superimposed against a black and white grid, a structure that, along with the rest of this stimulating show, dramatize the tantalizing connections the artists made with Shaker life.

Lauren Kaufmann has worked in the museum field for the past 14 years and has curated a number of exhibitions. She served as guest curator for Moving Water: From Ancient Innovations to Modern Challenges, currently on view at the Metropolitan Waterworks Museum in Boston.

With an overly long reach with too short arms, I find this ICA exhibit and its overall concept quite eccentric at best and incompatible with Shaker principles at worst. Traditional Shakers wouldn’t have had portraits painted of themselves, nor would they haver ever even hung paintings on their walls. Also, they would not have trivialized their own highly elegant form followed function approach to the world. Instead of a triumph, this exhibition is another disappointment at Boston’s ICA.

For better context regarding Shakers, see my previous article in Art Fuse:https://artsfuse.org/220259/visual-arts-commentary-an-enduring-new-england-design-influence-the-shaker-style/