March Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Classical Music

About a year ago, violist Timothy Ridout offered an expansive survey of music commissioned and/or championed by his great predecessor, Lionel Tertis. For 2025, he’s gone in a slightly smaller direction, with a Harmonia mundi disc of solo works, all of which—save one—are transcribed for his instrument.

About a year ago, violist Timothy Ridout offered an expansive survey of music commissioned and/or championed by his great predecessor, Lionel Tertis. For 2025, he’s gone in a slightly smaller direction, with a Harmonia mundi disc of solo works, all of which—save one—are transcribed for his instrument.

The outlier is by the British violist’s compatriot Benjamin Britten. His Elegy is an early work, written when the composer was just sixteen. But it broods with all the world-weariness of a young man who would someday write Peter Grimes and Billy Budd. Ridout’s performance—warm and intensely expressive—powerfully captures its deep sense of pathos.

There’s a similar sense of mystery, if not quite so much heartache, to be found in Caroline Shaw’s in manus tuas. Originally written for solo cello, the viola version works well, at least to a point, though the piece’s rough patches are no fault of Ridout’s. He navigates its play of ethereal arpeggios, sustained resonances, and chilly, sul ponticello sonorities with aplomb.

The violist’s adaptations of solo-violin fare are even more impressive.

Two of those, Telemann’s Fantasia Nos. 1 & 7 are heard in Ridout’s arrangements. They are, to a movement, thoroughly fresh and dancing, the bariolage episodes in the second movement of No. 7 emerging with real spirit.

Much the same can be said for his account of J. S. Bach’s Partita No. 2. Throughout, Ridout displays a terrific grasp of the music’s sense of sweeping, dancing energy. The Courante and Gigue are passionately driven. Though the Chaconne rightly towers over the entire undertaking, there’s an engaging directness and becoming humanity to Ridout’s larger reading: this is music he’s clearly lived with, knows, loves, and understands. That’s just what Bach’s music—and our troubling times—most need.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Robert Schumann came late to the violin sonata. Though he composed three of them, they all date from the last five years of his life. No. 3, in fact, was written so closely to the final downturn in his health that Schumann’s widow, Clara, opted not to have the score published; it didn’t appear in print until 1956.

Robert Schumann came late to the violin sonata. Though he composed three of them, they all date from the last five years of his life. No. 3, in fact, was written so closely to the final downturn in his health that Schumann’s widow, Clara, opted not to have the score published; it didn’t appear in print until 1956.

Mercifully, attitudes towards mental illness have, in recent decades, begun to improve. There’s certainly no hint of stigma in Alina Ibragimova’s traversal of the score in her new recording of the three Schumann sonatas with pianist Cédric Tiberghien.

If anything, the A-minor Third Sonata stands out as the most striking entry in the set, and not just because the violin writing in it is more idiomatic than in the earlier pair. Rather, Ibragimova and Tiberghien enthusiastically mine its ambiguities.

Its dialogues are hearty and vital, especially in the finale, whose mighty, Beethovenian transformation of themes comes off beautifully. So does the Scherzo, which emerges like competing views of a tempest: loud and blustery versus quiet and nervous—all of it underlaid with haunting rhythmic unsettledness.

The vigor of the players’ partnership carries over smartly into the first two sonatas, as well. Though the violin writing is generally unbrilliant and sits too low in the instrument, Ibragimova gets it all to speak fervently. There’s no shortage of exaggeration in her playing—of dynamics, articulations, and more—but everything is very flexible and characterful.

Tiberghien manages exquisite accompaniments—he shares the spotlight, rather than dominates it—and, in the process, underlines the brilliance of Schumann’s invention. The menacing 16th-note pedal point in No. 1’s finale and the luminously colored shadings of No. 2’s third movement are two special moments among many.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Popular Music

The late Martin Phillipps of the Chills. Photo: Alex Lovell Smith

The death of Chills singer/songwriter Martin Phillipps last year casts a large shadow over The Chills’s first posthumous album. For this project, he returned to songs he wrote in the early ‘80s but never released at the time. Phillipps admitted reworking them heavily from his perspective as a 60-year-old man. Spring Board: The Early Unrecorded Songs also draws on contributions from New Zealand musicians outside of The Chills, with Crowded House/Split Enz’s Tim Finn being the best-known.

Some of the tracks on Spring Board reflects youthful innocence, even idealism. “If The World Was Made For Me” muses on the possibility that we can “open our hearts and say exactly how we feel.” “Declaration” sets the stage by admitting that “it’s time to sort things out, set things straight, clear the air.” Phillipps was conscious that this album was the last way he could be honest, via music.

The Chills’ sweet spot, ‘60s-based psychedelic pop, is emphasized in the first half of the album, with contributions from Erica Scally’s violin and Oli Wilson’s keyboards. By its halfway point, though, Spring Board moves into a darker space. These songs make a far different impact now than if the Chills had recorded them in the ‘80s. Phillipps had personally experienced the downside of attitudes he might have romanticized decades ago. The “won’t you come and save me?” chorus of “Such Self-Pity” is performed now by a man who had battled heroin addiction, alcoholism, and hepatitis C. He takes some responsibility for his flaws, as on “Learn to Try Again.” “Lion Tamer” looks back on his quest to become a famous musician, which failed beyond New Zealand’s borders. Some songs aim for a warmer, more optimistic note, such as “I’ll Protect You.” Spring Board looks at the final stages of life with a vibrant clarity of vision: its final lines are “I don’t want to live forever, and I’m going to die alive.”

Reggie Harris (r) and Alastair Moock (l) at the Shalin Liu Performance Center. Photo: Steve Provizer

A number of the pieces in The Arts Fuse grapple with the thorny relationship between art and politics. A performance of gospel-infused folk music doesn’t raise any difficulties on that front. There may be some arguments regarding the roots of what we have come to call “folk” music, but it is a musical genre that has long been clearly identified with a (leftist) ideological point of view. The criteria for critiquing a recent live performance of Reggie Harris and Alastair Moock at Rockport’s Shalin Liu Performance Center comes down to deciding if the performers delivered their political message in an entertaining and skillful way. Happily, the duo were up to the task.

In this free performance, these guitarist/vocalists presented songs and conversation that explored the vexing social issues of our time, celebrating those who acted to promote justice and equality. The duo were friends before they created this act, and they appreciated and encouraged each other with ease. The relationship between Harris, who is Black, and Moock, who is white, provides a platform for launching into conversations about race, equity, and personal responsibility. Harris and Moock do a lot of performing and counseling in schools. The intimate, friendly bond between these men of two different races is, in itself, a very important part of the presentation.

Both are able guitarists who sing and harmonize well, although Harris has a more supple voice, able to provide ornamentation and even improvisation to the routine. Their songs included standards, like “Wade in the Water” and “This Little Light of Mine,” as well as originals, such as Moock’s “Be a Pain” and Harris’s “Roll On, Woody Guthrie”. This is good and valuable work — mobilizing art to further understanding.

— Steve Provizer

Marc Ribot Quartet at Arts at the Armory. Photo: Paul Robicheau

Guitar savant Marc Ribot’s rare local appearance at Somerville’s Armory on Feb. 21 proved two things. One, that experimental music akin to New York’s “downtown” scene can find a home in Arts at the Armory, where Ribot filled its performance hall with an SRO audience beyond the cabaret tables and chairs. The other was that Ribot – whose 40-year career has ranged from mainstream artists Tom Waits and Robert Plant/Alison Krauss to the avant-garde Lounge Lizards and John Zorn – can hatch a new band with precise unpredictability.

Advance word on Ribot’s Hurry Red Telephone quartet, which was playing only its second date, suggested continuity from his early aughts project Spiritual Unity, inspired by Albert Ayler’s avant-jazz squalls. Other than Ribot, the sole carryover was drummer Chad Taylor. Spiritual Unity bassist Henry Grimes and trumpeter Roy Campbell’s spots were filled by bassist Sebastian Steinberg (of arty alt-rockers Soul Coughing) and guitarist Ava Mendoza. Given her roots in classical, blues, punk and avant-jazz, Mendoza echoed Ribot’s versatility and played his foil at the Armory, if not so much in terms of dissonant shredding. Following off charts of Ribot compositions, the players largely felt each other out musically, resulting in more intricate contemplation than noisy energy.

The night began with an improvised invocation around the gnarly refrain of Ribot’s old hollow-body jazz guitar, building atop Taylor’s tom patterns and Steinberg’s bowed and plucked bass thrust. It resolved in Ribot reciting the Richard Siken poem “Several Tremendous,” revealing the phrase “Hurry red telephone” amid stanzas about angels. The band then tackled “New Monster,” bringing the 75-minute set to an early peak. Taylor rolled into a double-time rock beat and Ribot dropped a skittering lead, then urged on Mendoza, who shifted from vibrato chords to Mahavishnu-like ferocity. At one point, Taylor and Steinberg stopped to clap in random accompaniment. Yet the guitarists favored clean, interlocking lines at times reminiscent of ’80s King Crimson or late ’60s Grateful Dead — more evident when their wiry blend floated on a bit too long before “Human Sacrifice” galloped into a closing tempest not to be topped – until another combo this fearsome can grace the Armory’s space.

–Paul Robicheau

The appeal of the existential nausea dramatized in Headache and Vegyn’s collaboration, The Head Hurts but the Heart Knows the Truth, is undeniable. In just 8 tracks over 30 minutes, electronic music producer Vegyn and writer Francis Hornsby Clark explore a plethora of experiences, phantasmagorical and otherwise, spawned by the uncertainty of contemporary life, from the suicide attempt in Business Opportunities to the yearning for love in Bucket Listener. The confessional yet absurd lyrics (“the enemy is yourself posed as a question” and “love is the only thought and pain is the only feeling”) are set against a catchy backdrop of lush synthesizers, moody soundscapes, and infectious IDM beats. At times, the recording’s weaving, cerebral, non-linear narrative amounts to a bundle of Zen koans mixed in with haphazard thoughts, “though fish are not animals, they do have feelings. ”

Francis Hornby Clark’s perceptive, highly articulate monologues come via AI, but they are visceral in the original sense of the word — these are primal effusions. Few songwriters have bared their soul with such raw power. How did the duo manage to create such a rich AI sound? Nearly every other use of AI sounds completely lifeless. If this album offers a glimpse of what the future of AI in music might be, I’m all for it.

— Jacob Risch

Film

A scene from Ex-Husbands. Courtesy of Bold Choices Prods., Rathaus Films, Pimienta Films, San Sebastian Film Festival

Griffin Dunne and Rosetta Arquette celebrate the 40th anniversary of their wacky romance in Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985) by appearing as a 60ish couple about to get divorced in the tender, appealing Ex-Husbands. In this male-oriented semi-soaper, there is little gained for guys being on the outside. Both dentist Peter Pearce (Dunne) and his son Nick (James Norton) are suffering and floundering because their women don’t want them around. And Peter’s septuagenarian father Simon (Richard Benjamin), who cockily walked out on his wife six years earlier, is now senile and alone, staring up without comprehension at a framed movie poster of his once-beloved movie, Ernst Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be.

The marital troubles happen in New York City but they surely don’t go away when both father Peter and son Nick try escape to a Mexico beach. Peter pledges to be on his own there so that Nick can enjoy a bachelor party with his goofy, emotionally retarded pals. But Nick soon needs the solace of his dad because the bachelor party has a spoiler: Nick’s girlfriend has called off the marriage.

Oh, men! There’s only one among these thirty-somethings flailing on the beach who has his head on straight. That’s Peter’s second son and Nick’s post-college brother Mickey (Miles Heizer), who has not only arranged and produced the bachelor party but is dealing in a mature way with his recent “coming out.”

Despite the melancholia in the air, Ex-Husbands is still fun to watch for the atmospheric use of scenic Tulum on the Yucatan Peninsula. Director Noah Pritzker has cleverly cast his ensemble of stumbling males, and Heizer as the gay brother is especially winning. I wish there was more of Rosanna Arquette in the film. What a 1980s favorite, Desperately Seeking Susan (1985) and more. But the real disappointment is how little we get of 85-year-old Richard Benjamin, whom I remember so fondly for Goodbye Columbus (1969) and many juicy roles in the 1970s. In the one scene in Ex-Husbands in which he claims his male freedom to divorce, we can see that Benjamin still has his rich actor chops. Too bad he’s next seen dazed in a chair and without a voice.

So whom does this leave us with? Griffin Dunne, also executive producer of the film, giving the screen performance of his life. He’s just great as this shlumpy needy dentist who thirsts for his sons to want to be with him and his estranged wife to miraculously change her mind and drop the divorce proceedings. Can we assume that the title Ex-Husbands is meant for us to recall John Cassavetes’ 1970 Husbands? While the first is a lacerating take on toxic masculinity, this second act is a sweet, gentle story of men whose “masculinity,” whatever that even means, is getting them nowhere. But there’s no preening Trumpism here, only the wish for men to find themselves a bit and a slight hope to get back with their women.

— Gerald Peary

Morena Baccarin and Edward Burns in Millers in Marriage. Photo: Myles Aronowitz / Republic Pictures

At first glance, Millers in Marriage has what it takes to be a great film. Written and directed by and starring Ed Burns (who also helmed 1995’s The Brothers McMullen), this contemporary saga features an outstanding cast. The Miller siblings, all in their early 50s, are gathering for a weekend at one of their country homes in upstate New York; it’s not really necessary to know which one, because these well-to-do folks all have country homes in upstate New York. Except for Eve (Gretchen Mol), who still lives in Manhattan, a former singer-songwriter whose band was on the rise until she married Scott (Patrick Wilson), a touring musician whose controlling, jealous ways cooled her dreams of stardom. His alcohol-infused outbursts have left her feeling defeated, and Eve is reevaluating her life.

Meanwhile, music critic Benjamin Bratt, who’s had a crush on Eve for 25 years, reappears in her life, still smitten, to interview her for his book. Andy Miller (Burns) has recently split from his young supermodel wife Tina (Morena Baccarin), and has started seeing his friend Renee (Minnie Driver). But Tina is still hovering in a manipulative way, making Renee wary. Maggie Wilson (Julianna Margulies) is a successful writer married to Nick (Campbell Scott), a once-celebrated novelist who blames Maggie for his lack of creative spark (the conflict is reminiscent of the contentious, competitive marriage between writers Diane Keaton and Richard Jordan in 1978’s Interiors). The web of connections is intriguing: each couple struggles with dissatisfaction, the lure of infidelity, and coming to terms with the limits that time and choices place on our lives. The performances are excellent throughout, especially from Mol, Burns, Bratt, and Scott. Unfortunately, the narrative becomes tedious, constricted by its reliance on exposition-laden dialogue and heavy-handed flashbacks, ignoring elemental rules of cinematic storytelling (like “show, don’t tell”). The cast skillfully transcends the leaden screenplay, holding the drama together, if only barely. Kudos to composer Andrea Vanzo for a tensive, beautiful piano score that enhances and elevates the story.

— Peg Aloi

Books

Opera, with its steep ticket prices, has long been associated with the wealthy few. But the genre has also flourished widely and under more modest circumstances. Singers who, because of racial prejudice, were not allowed onto the opera house’s stage have often performed for members of their own community. And enterprising composers who were similarly stigmatized have sometimes persisted in writing operas that they knew were unlikely to get professionally staged—or sometimes heard at all.

These and other counter-histories of opera, with specific regard to the world of Black America, are carefully reconstructed in Lucy Caplan’s fascinating new book, Dreaming in Ensemble: How Black Artists Transformed American Opera (336 pages, Harvard University Press).

Caplan here offers a many-sided portrait of what she calls a “Black operatic counterculture,” in which musicians and their supporters reshaped the genre for use within the local community or managed to make some inroads into wider public performance. Many singers who mastered classical vocal technique sang operatic excerpts in private homes or public halls. By the years 1941-62, some got to perform in staged and costumed productions by Mary Cardwell Darson’s pathbreaking National Negro Opera Company.

We also learn of the bold and forthright music criticism penned by Nora Holt in 1917-23 in the Chicago Defender; guest roles for Black sopranos (as Aida) with otherwise white opera companies; a 1932 performance of Tom-Tom, a “revolutionary Afrodiasporic epic” by Shirley Graham, before an audience of thousands in the Cleveland baseball stadium; and visionary operas by Harry Lawrence Freeman that went largely unheard.

A mix of local successes and momentary dead ends, these efforts testify to a desire for achievement, self-expression, and concern for community that would eventually lead—after this book ends—to the triumphs of such notables as singers Leontyne Price and George Shirley, composer Terence Blanchard, and librettist Tazewell Thompson (Blue, written with white composer Jeanine Tesori).

— Ralph P. Locke

Amid Donald Trump’s dystopian whirlwind of chaos and destruction, Pico Iyer’s Aflame: Learning from Silence (240 pages, Riverhead Books) offers valuable advice: tune out the ugly noise and focus on connecting more deeply with oneself and others to marshal righteous action. The lessons in his memoir are drawn from notes taken over the course of his over 100 silent retreats in a Benedictine monastery in Big Sur over the last three decades.

Iyer originally came to the center in 1991 after his home burned to the ground and he had no place to stay. He returned again and again: after his father’s death, his child’s cancer treatments, and between international travel writing assignments. In this retreat he discovered that the solitude was “not so much about escape as redirection and recollection.”

Instructions to retreatants are simple: Put the whole world behind you and forget it. If your mind wanders don’t fret. Simply empty yourself out and sit waiting. Over the years, Iyer found that silence and contemplation liberating — it unleashed his creativity. Experiencing uncluttered undistracted time made him realize that “the point of being here is not to get anything done; only to see what may be worth doing.” Repeatedly, Iyer emerged more engaged with his surroundings and a renewed sense of direction.

In addition to beautiful descriptions of the wilderness setting, Aflame is enlivened by loving portraits of sweet-tempered monks as well as passing conversations with fellow seekers. Wisdom from spiritual, philosophical, and literary visionaries are peppered throughout, including reminiscences of Zen practitioner/songwriter Leonard Cohen.

Readers are reminded usefully reminded that clarity and silence are “available in many settings, not always monastic.” We are encouraged to pay more attention to our surroundings in daily life. The book’s title is drawn from a Christian proverb: “If you so wish, you can become aflame.” Iyer’s heart-felt wisdom urges a deeper examination of self as well as deepening our connection to others. Compassion and empathy move us forward — they are essential tools in a profane world.

— John Killacky

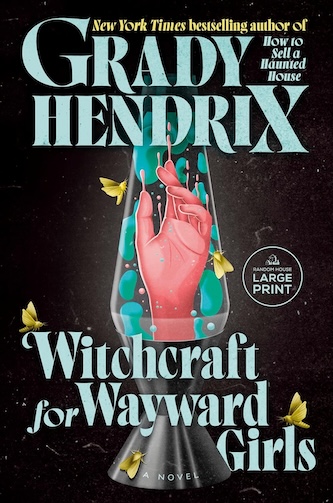

In Grady Hendrix’s latest novel, Witchcraft for Wayward Girls (469 pages, Berkley Books), he uses body horror as a means to explore his protagonist’s psyche as he delves deep into the systemic oppression of women’s rights.

Set in Florida during the ’70s, the narrative centers on a 15-year-old girl, Fern, who is admitted into a home for unwed mothers. There, pregnant teenage girls have their babies and are then coerced to give them up for adoption. Some of the tortures the young women endure include invasive medical procedures and insane diets. Fern and her new friends in the institution are desperate to gain some measure of control over their bodies. How do they find it? Through the discovery of a book of witchcraft.

Hendrix vividly depicts the physical and psychological violence the girls face. The body horror, especially in the birth scenes, is intense. The brutal treatment motivates Fern and others to renounce God and sell their souls to the infamous Miss Parcae. She promises to give them the means to fight back against the people who are mistreating them. However, Miss Parcae has a secret agenda and a dark reason for targeting these girls.

Miss Parcae aside, the witches aren’t the story’s focus, which may disappoint fans who expect a supernatural, thrill-focused gnre ride. The emotional trials and tribulations of Fern and her fellow sufferers — struggling to surmount a cruel reality — are at the heart of this story. Hendrix’s carefully constructed fright scenes are present, as in his previous work, How To Sell A Haunted House, but there are fewer of them.

Witchcraft for Wayward Girls is a powerful tale about friendship, forgiveness, and desperation. The novel is frightening but it is also deeply moving. Its characters fight for an acknowledgement of their value — for respect and freedom. Those barriers to a satisfying life still face women, in some form or other, today.

— Ana Peres

Cletham Classics is an odd series distributed by Columbia University Press. It is billed as “an innovative new range of thoughtfully designed books comprising both canonical texts and lesser-known works by much-loved writers. Cletham’s carefully selected titles and dynamic visual style make for an indispensable and ever-expanding collection.”

On the one hand, the rookie lineup is nicely varied. Some of the titles sparked my curiosity, such as Joseph Conrad’s last completed novel, The Rover, as well as essay collections by Aldous Huxley (On the Margin) and C. K. Chesterton (Fancies Versus Fads). More predictable, easier to find fare, such as Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room and Anton Chekhov’s Love and Other Stories, not so much. The print size is comfortable to read, and the volumes are easy to slip into your pocket. They are priced between $14 and $20.

Keep that price point in mind because this is a no-frills product. And when I say no frills, I mean nada frills. No critical notes, no background material, no introductory overview — and the box-car visual format (two blocks, two colors) is anything but dynamic. I read Knut Hamsun’s short chronicle of a love story short-circuited by class, 1898’s Victoria, and enjoyed it immensely. The Proto-Modernist narrative is an early example of what French psychologist Jacques Lacan would call a quest for “an object of impossible desire.” Unless you did some detective work online, though, you wouldn’t know that Arthur G. Chater’s translation from the Norwegian is a reprint of the 1925 Knopf edition, the same version in English that is available, for free, via Project Gutenberg. Indispensable? Nice to have around? Up to you …

— Bill Marx

Public Art

A section of David Fichter’s Mystic River Mural. Photo: Somerville Art Council

A mural has been growing in Somerville for almost three decades. Set along Mystic Avenue, this project has been the educational/artistic brainchild of master muralist David Fichter. Now almost a quarter of a mile long (1200’+ wide), the mural is painted on 10’ high panels that are installed on the concrete retaining wall of US I-93.

The project was launched in 1996. Sponsored by the Somerville Arts Council the mural has drawn on the knowledge of environmental educators and surrounding community and open space organizations, naturalists, and historians. In the process, Fichter has developed a rather spectacular local youth (14-19 years old) summer employment program that combines making art with hands-on environmental education. Many of the participants are residents and high school students from the Mystic Housing Project located across the street from the lengthy mural. These young assistants are gathered from an international community of youth living in Somerville, coming from a wide-range of countries that include El Salvador, Nigeria, Haiti, Vietnam, Brazil, and Ukraine. National and ethnic music and food of these countries of origin is often shared by the participants while working on the mural.

Each year, a curriculum is developed through an adventurous exploration of an aspect of the Mystic River Watershed. This process gives birth to an annual new theme that inspires the arrival of new pictorial panels..

Commissioned to work across the US and in many different countries, Fichter has been creating murals and mosaics for nearly five decades. He and teams of adolescents have finished well over 200 permanent murals and over 75 additional commissioned projects. Located primarily at schools, libraries, health centers, universities, and other public spaces. These murals are inevitably colorful, figurative, and vibrant, thoughtfully exploring universal themes that reflect issues rooted in local history, multiculturalism, and nature.

Two large and prominent Fichter murals are displayed on the side of Trader Joe’s on Memorial Drive in Cambridge and “The Potluck” on a wall in Central Square. Think of him as a contemporary Johnny Appleseed, artistic version. The muralist has planted his work to generate pride in our shared humanity and our desire to save and celebrate our natural environment.

— Mark Favermann

Tagged: "Aflame: Learning from Silence", "Dreaming in Ensemble: How Black Artists Transformed American Opera", "Ex-Husbands", "Millers in Marriage", "Spring Board: The Early Unrecorded Songs", "The Head Hurts but the Heart Knows the Truth", "Victoria", "Witchcraft for Wayward Girls", Alastair Moock, Ana Peres, Cletham Classics, David Fichter, Edward Burns, Grady Hendrix, Griffin Dunne, Hurry Red Telephone Quartet, James Norton, John Killacky, Knut Hamsun, Lucy Caplan, Marc Ribot Quartet, Mark Favermann, Martin Phillipps, Morena Baccarin, Mystic River Mural, Paul Robicheau, Pico Iyer, Reggie Harris, Richard Benjamin, Rosetta Arquette, Steve Provizer