Film Reviews: DocTalk — Legal Briefs at the 2025 Oscars

By Peter Keough

The 2025 Oscar nominated documentary shorts indict the justice system.

2025 Oscar Nominated Shorts: Documentary. At the Coolidge Corner Theatre, beginning February 21.

This year the Academy selected a stronger slate of nominees than usual in the short documentary category, perhaps because the timely theme of justice, in one form or another, inspires each.

A scene from Instrument of a Beating Heart. Photo: Doc NYC

Even Ema Ryan Yamazaki’s ostensibly lighthearted Instruments of a Beating Heart takes a look at the issues of crime and punishment, if only on the level of a second-grade music project. In a Tokyo elementary school an adorable little girl auditions to play the drum in her class’s performance of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” Nerves betray her and she fails, but her female homeroom teacher encourages her to try again with the cymbal and she succeeds.

But rehearsals do not go well. Perhaps because of her self-consciousness at performing in front of people, she keeps screwing up, arousing the ire of the male music teacher, who singles her out and shames her before the others. To their credit, the other girls do not turn on her. Earlier we had seen some show their empathy, weeping for other classmates who were cut during the auditions. Also, the kind homeroom teacher consoles the girl and encourages her to keep trying. In a pedagogical version of good cop/bad cop the two teachers nurture the child so she successfully fulfills her role in the group performance. The film is thus an ode to joy, but also a tribute, of sorts, to regimentation.

A classroom is also the focus of Kim A. Snyder’s Death by Numbers, but instead of poignancy and affirmation it teaches a lesson in prevailing over horror and evil. On February 14, 2018, Nikolas Cruz entered the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida with an assault rifle and murdered 17 people. One of those who survived was Sam Fuentes, who huddled under a desk in her “Holocaust Studies” class as a bullet struck her leg and fragments lacerated her face.

In 2022, her physical wounds have healed, but the psychological trauma remains (Fuentes notes in her eloquent voice-over narration, drawn from her diary, that three other survivors have since committed suicide). Still, she agrees to confront Cruz in court and testify at his sentencing hearing. Though torn by rage and contempt and a sense of futility, she delivers a devastating statement that rises above mere condemnation and becomes a transcendent dismissal of a puny, pitiful individual who will remain a cipher despite the anguish he has caused.

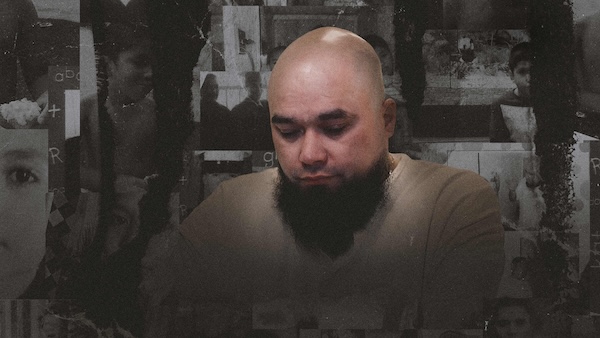

A scene from Smriti Mundhra’s I Am Ready, Warden. Photo: Paramount +

Cruz escaped the death penalty and was sentenced to life without parole. Not so lucky was John Henry Ramirez in Smriti Mundhra’s I Am Ready, Warden, but in this case the criminal has achieved a kind of redemption. His fate calls into question the validity and value of the system that has condemned him.

In 2004 the then 19-year-old ex-Marine brutally stabbed to death 46-year-old Pablo Castro, manager of a convenience store, in a botched robbery. Ramirez fled to Mexico, married and had a son, but was tracked down, tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. In 2022 the sentence will be upheld: after several appeals, the dogged intercession of his once pro-capital punishment spiritual advisor, and requests for clemency from the DA, the sentence will be upheld.

It is now six days before he will be put to death by lethal injection, and Ramirez is okay with that. He has fully acknowledged his guilt and over the years his Christian faith seems to have transformed him into someone much different from the violent soul he had once been. But Castro’s son, Aaron, will have none of it. He remembers being a kid and seeing his father lying on the street in a pool of blood, a kind and peaceful man stabbed 29 times by a demonic stranger. Yet, in addition to his rage and grief, Aaron also shares some of his father’s empathy and, as the execution date approaches, his feelings are mixed.

A scene from Bill Morrison’s Incident. Photo: Doc NYC

Sometimes the killers go scot-free, and it is often because they wear a uniform and a badge. Bill Morrison’s Incident opens with a Google Earth animated zoom from outer space to a silent CCTV view of a peaceful-seeming street on Chicago’s South Side. Subtitles establish the date as July 14, 2018, 5:30 p.m. In a few minutes Harith “Snoop” Augustus, a local barber, will be shot to death by Officer Dillan Halley. The first words heard after the killing are Halley on the radio shouting, “Shots fired at police!”

That is false, but from that untruth springs the official cover story that distorts the murder of an innocent man into a matter of self-defense and a justifiable use of force. Expanding into a four-way split screen, Incident relentlessly pares away at the lies to arrive at the facts in a strategy reminiscent of Errol Morris’s Thin Blue Line, except that here the images used are not reenactments but actual footage from the officer’s body cams and from surveillance video. As the guilty policeman and his partner sped away, working to get their stories straight (Halley neglects to turn off his body cam so their fabrications are audible), and an angry crowd gathers to protest yet another police shooting, the body of Augustus lies unattended in the street.

Morrison’s previous work has more or less exclusively drawn on found footage, usually vintage and distressed, but more for aesthetic than reportorial purposes, as in Decasia (2002). An exception is his masterpiece Dawson City: Frozen Time (2016) subtly delved into the political and social subtext of its raw material. While it too is subtly constructed, Incident delivers an unambiguous message. We learn that the truth was stifled, justice was denied, and Halley got off with just a two-day suspension. An epilogue notes that at his memorial service Augustus, who was the father of a five-year-old girl, was eulogized as “a quiet, patient, and peaceful man,” words eerily similar to those describing Pablo Castro in I Am Ready, Warden.

Leonard Bernstein and Orin O’Brien in footage from The Only Girl in the Orchestra. Photo: Double Bass HQ

Some eight decades older than the aspiring cymbalist in Instruments of a Beating Heart, Orin O’Brien, the title double bassist of her niece Molly O’Brien’s The Only Girl in the Orchestra, never wanted to be more than a member of the band. That’s why she chose the ungainly instrument, because she liked to play with other musicians but had no ambition to be a soloist. However, she found herself in the limelight when she became the first woman in the New York Philharmonic, hired in 1966 by Leonard Bernstein, who described her as “a source of radiance” (the press was less generous, one wag writing that she was “as curvy as the double bass she plays”). There she remained for 55 years, retiring in 2021.

Today, she still carries the big fiddle around as she teaches other aspiring bassists, students who clearly love her. O’Brien demonstrates her solo skills by playing passages from Prokofiev’s opus 60, the second movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, and others. She is indeed a “source of radiance,” but the director makes a mistake common in films that explore the lives of elderly family members: she grafts onto it details of her own life, inadvertently reducing the self-effacing but pioneering musician to a supporting role in her own story. Nonetheless, the message is clear: because of the courage and determination of pioneers like Orin O’Brien, we seem to have come a long way from the days when such accomplishments were barely tolerated, let alone acclaimed – a benighted time to which we seem to be returning.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).