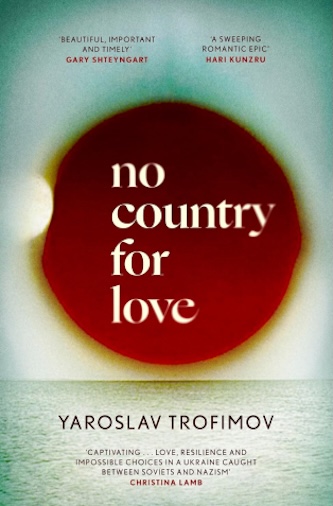

Book Review: Surviving Stalin in “No Country For Love”

By Peter Keough

In this compulsively readable novel, a Ukrainian Jewish woman does what she needs to survive in the nationalistic, anti-Semitic, and misogynistic Stalin-era Soviet Union.

No Country for Love by Yaroslav Trofimov. Little Brown. 384 pages. Hardcover $22.76, paperback $17.99.

Ukraine might be the bloodiest country on earth. Since the 20th century, wars, revolutions, pogroms, mass deportations, Nazi genocide, plagues, and famines have taken the lives of millions. Most of this carnage is thanks to their neighbor Russia, now in the third year of a ruthless, unprovoked invasion, the full toll of which has yet to be determined.

Ukraine might be the bloodiest country on earth. Since the 20th century, wars, revolutions, pogroms, mass deportations, Nazi genocide, plagues, and famines have taken the lives of millions. Most of this carnage is thanks to their neighbor Russia, now in the third year of a ruthless, unprovoked invasion, the full toll of which has yet to be determined.

Yaroslav Trofimov, the Ukrainian-born Wall Street Journal reporter whose 2023 book Our Enemies Will Vanish: The Russian Invasion and Ukraine’s War of Independence offers trenchant, first-person reporting of the first year of that conflict, provides personal and historical context for the conflagration in his first novel, No Country for Love. Trofimov is no prose stylist, but this account, based on his own family history, is compulsively readable, invaluably informative and insightful, and often powerfully moving. Like Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate or Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago, the narrative engages with vast historical catastrophes by focusing on the individuals caught up in them. The story also vividly evokes the trauma of living under a dictatorship with no good choices on how to survive.

Based on Trofimov’s own family history, it opens in medias res in 1953 with a cold-blooded assassination. It then flashes back to 1930 as 17-year-old Debora Rosenbaum, fresh from her backwater hometown of Uman, arrives breathlessly optimistic in Kharkiv, capital of the then Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. She’s there to work at the new tractor factory, but she is hoping to study literature at the university. She is agog at the vitality of the city, its many bookstores, shops, beauty salons, and the presence of a vibrant Ukrainian cultural elite of which she hopes someday to become a member. But for now she must be content painting banners reading Death to the Clique of Traitors and Bourgeois Counter-Revolutionaries! for the factory’s Political Unit.

This initial glow of limitless possibilities dims a bit when she learns that, despite Soviet ideals to the contrary, women are still seen as a commodity. A drunk at a party tries to grope her, but she’s rescued by a shining knight – Samuel Groysman, a cadet in the air force, who whisks her to the dance floor. Their romance is interrupted when he is assigned to another city, but it resumes a couple of years later when he encounters her on a tram, where he again rescues her from the attentions of another inebriated asshole. This time they get married, and again the future looks bright.

As a Ukrainian, a Jew, and a woman, Debora would seem to have three strikes against her in the nationalistic, anti-Semitic, and misogynistic Stalin-era Soviet Union. These vulnerabilities notwithstanding, she still comes from a world of privilege. Her father Gersh, an assimilated Jew who before the Revolution was the bourgeois owner of a dairy processing plant, has managed to conceal his non-proletarian background from Soviet overseers. He has attained a comfortable spot on the People’s Commissariat of Trade. As such, he manages to keep his family well-fed and relatively pampered.

Debora’s marriage to Samuel initially brings even more security. They have a son, Pasha, and Samuel has apparently settled into the Stalinist system and is about to rise in the ranks. But a jealous neighbor seeking their apartment (beware of jealous neighbors seeking apartments in the Soviet Union) reports him for uttering pro-Ukrainian, anti-Stalin remarks. He is arrested and sentenced to exile in Siberia.

After Samuel is not heard from for years and is assumed dead, Debora succumbs to the wooing of Maslov, a boorish officer in the NKVD (a precursor to the KGB and FSB). Though it would have been tempting to caricaturize Maslov as a villain, Trofimov’s characterization of him exemplifies his subtle analysis of and empathy with his characters. None of them are entirely good or evil; all of them have human weaknesses and strengths and possess a potential for redemption. Maslov might be a torturer and murderer of the innocent victims of an unhinged, paranoid tyranny, but he takes no pleasure in his work, though he does enjoy its benefits. In some ways he proves to be a good husband to Debora, who would be doomed without him, and a loving father — if a poor role model — to his stepson Pasha.

Nonetheless, his profession is morally inexcusable, a fact that Debora recognizes. But her marriage to Maslov is not the first time she has compromised principle to survive in an evil, inescapable regime. While at the university she was brought in by the NKVD for questioning about a friend: she offered possibly incriminating testimony. While safe and well fed in the university — and relatively ignorant of the ongoing Holodomor, the famine brought by the Soviet seizure of the Ukrainian grain harvest that killed millions — she visits a close acquaintance in one of the most stricken areas, bearing not food but a stuffed pink dog for her friend’s son.

But the marriage proves a lifesaver with the arrival of Germany’s invasion. Her husband manages to extricate her, her mother Rebecca, and Pasha from one hotspot to another, often just in time, as the Nazi blitzkrieg advances. They escape from Kyiv days before the murder of tens of thousands of Jews at Babi Yar. Seeking refuge in Stalingrad, they are again evacuated as the Nazi assault besieges the city, a battle that will prove a disastrous German defeat and a turning point in the war.

With peace comes not renewed tranquility but a deterioration in Debora’s situation and intensified assaults on her conscience and self-respect. Gratifyingly to the reader, she at last reaches a point where she must resist. “[It]’s the good ones who die early,” she tells her mother. “I am not yet ready to die. I won’t be good anymore.” With cold calculation she assumes the role of an avenging femme fatale. Shockingly, history, long her antagonist, abets her scheme. Though it may be no country for love, perhaps it will prove to be a country for justice.

Editor’s Note: Trofimov will be speaking about his novel at several upcoming events: Feb. 18, Miami, World Affairs Council; Feb. 20, Chicago, University of Chicago, 12:30 p.m.; Feb. 24, Washington, D.C. Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies; Feb. 25, Philadelphia, World Affairs Council; Feb. 26, New York City, University Club; Feb. 28, Washington, D.C., Atlantic Council, 10 a.m.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).