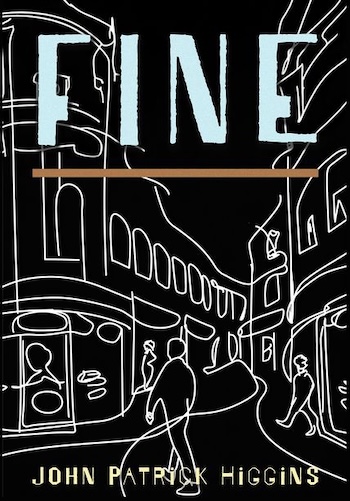

Book Review: “Fine” — Lad Lit That’s Keenly Aware of the Human Condition and Its Afflictions

By Vincent Czyz

John Patrick Higgins is a deft writer whose prose often displays a spare lyricism.

Fine by John Patrick Higgins. Sagging Meniscus Press, 208 pages, $19.95.

The term Chick Lit (not to be confused with the trademarked gum) has fallen out of flavor — I mean favor. But it once described a type of fiction, usually commercial, that targeted female readers. Typical elements included professional woes in a male-dominated workplace, friendships among women, romantic relationships (the latter especially). Critics hailed it as a new genre in the ’90s but Jane Austen was writing novels addressing the same concerns nearly two centuries earlier. Austen fans might object that her books rank as first-rate fiction, but, reactionary arguments to the contrary notwithstanding, genre isn’t what decides whether a novel has earned a place beside the classics or a trip to the recycling bin.

Lad Lit, the male version of Chick Lit, is represented by the likes of Nick Hornby (you may recall About a Boy or High Fidelity) and Nick Spalding, who’s published 20 titles and counting. Fine by John Patrick Higgins may also qualify as Lad Lit so long as the reader bears in mind that beneath the humor permeating this novel is a literary sensibility keenly aware of the human condition and its afflictions.

Paul Reverb, a man in his mid-50s with an uninspiring job at an insurance company, moonlights as a novelist. As the book opens, however, he’s hit a creative dead-end: Try as he might, he can’t advance the plot of his tale about a vampire hypnotist and his would-be slayer, Robinson (at least that’s the name Robinson starts out with).

“I returned to the page, staring blankly at Robinson. I had no idea what to do with Robinson. I had forgotten who Robinson was. Why would my readers give a shit about Robinson if I knew nothing about him? What sort of a name was Robinson anyway?… It was an ersatz name: no one was actually called Robinson…. I drew a line through Robinson.” Eventually, Robinson is renamed Wainwright.

This is not, however, a story about a writer agonizing over his magnum opus; one can only take a novel about a vampire hypnotist so seriously (Reverb himself doesn’t display much respect for his literary handiwork). Rather, Reverb’s inability to write is representative of where he is in life — stalled, stagnating, sans an exit strategy.

His creative difficulties, in fact, may be the least of his problems. He lives alone in a London flat he inherited from his deceased parents. (“I was alone,” Higgins writes at one point, “I was so alone.”) He is childless. He’s desperate for a romantic relationship though he wouldn’t mind the occasional one-nighter to tide him over. Unfortunately, he’s a strike-out artist no matter the field he plays on. “I was a man whose leisure hours were chiefly filled with drinking, masturbating, and listening to records,” he laments. “If I opened the curtains, it was a good day.”

In addition to struggling with loneliness and writer’s block, he’s increasingly aware that he’s getting on in years. “My body disgusts me now…. My flesh has the color and consistency of chewing gum on a warm radiator.” Two pages later he concludes, “This was the best it was ever going to be. This was it until it got worse.”

And, no, that doesn’t quite cover what’s ailing Paul Reverb. On top of all that, he’s a man “in retreat from the 21st century.” He doesn’t “like anything about it. The cinema, the music, the politics, the people.” One fun byproduct of his era-discomfort is that the reader is treated to lots of talk about ’80s bands and their music. Of course, that’s only a plus if you’re into Depeche Mode, Black, The Smiths, and the other alternative groups that dominated the music charts 40 years ago.

In his youth, Reverb himself was a singer and bassist in a rock band (with the unappealing name of The Franks). Alas, by his own admission, he wasn’t all that good. Worse, he suffered from proximity to his best friend, Brendan, the band’s lead guitarist, who was tall, fetching, and excelled at just about everything he tried his hand at.

Fine is essentially episodic, a series of incidents and escapades that dramatize Reverb’s unenviable life in the present and flash back to his equally unenviable past. The action tends to be of the mundane sort. The novel opens, for example, with Reverb trying to work on his novel in a café and failing to thwart a thief who poses as another woman in order to steal her purse (which purse he was entrusted with guarding). On a London bus he resorts to racial profiling, which, predictably, doesn’t end well. While he’s indulging in a favorite pastime, two window washers literally catch him with his pants down (if embarrassment were lethal, the novel would’ve ended there). He spends too much time hankering after Kat, a 22-year-old barmaid. When he finally gets the guts to make his move, in walks her boyfriend. (“He was six foot four and in a band. Handsome, if you like that sort of thing…. Who’s in a band nowadays? Who wants bands? Why couldn’t he do something useful, like pull plastic out of the sea or give mouth to mouth to a dying bee? The planet’s on its arse, mate, and you’re fucking about in a band?”) Looking for a change of scenery, he sets out for Northern Ireland to visit Jo, his “sexiest friend.” It just so happens her Irish husband is nowhere in sight, but he misplays his hand yet again and the get-together ends rather ingloriously.

And so it goes. Since the action is fairly minimal, the novel is sustained largely by dialogue and Reverb’s mind chatter. We listen in as he self-analyzes, strategizes, slags off contemporary society, and longs for the ’80s. This approach asks a lot of the narrative voice. Fortunately, Higgins is a deft writer whose prose often displays a spare lyricism. This is in evidence as he describes nocturnal London: “I like the city after dark: the amber halos around the lampposts, the powdery stone, the restless tide of the traffic…. Its tempo relaxes, its sounds distort. It’s like walking on a gray, empty moon. The distance between people lengthens and the people you do see are adrift on a lunar landscape: unbalanced, aware of their own gravity, bobbing like balloons. The air is colder, cleaner, more visible.”

Writer John Patrick Higgins. Photo: Sagging Meniscus Press

While Reverb is a witty raconteur, and I doubt there’s a page that went by that I didn’t laugh at least once, the novel is not without tragedy. One of Reverb’s closest friends, who was all potential when they were young, never realizes his talent, descends into alcohol addiction, and overdoses — perhaps deliberately.

There’s also Reverb’s caustic Aunt Sylvia, the last relative with whom he has any contact, which, admittedly, is minimal. He visits twice a year, and the two engage in lengthy sniping sessions that disguise their mutual discontent. But then Sylvia takes a nasty spill, and her health rapidly deteriorates.

A month ago, she was fine, her posture good and her conversation reassuringly waspish. She seems to have aged twenty years since leaving the hospital. Before she was an immortal: my aunt, always and forever, an immutable fact. She would always be there. Now she seemed to be fighting every second just to stay in the world, every thud of the walker’s rubber stopper is a piton hammered into rock ….

While loneliness, aging, and death are overriding concerns in the novel, Fine also takes on the winner-take-all society Western capitalism has manufactured, which implies that unexceptional is synonymous with loser (a signature insult of Felon 47, who is the epitome of everything that’s wrong with capitalism). A society in which average is somehow shameful. In a 1989 interview with Marlon Brando, Connie Chung pitches the idea that he’s the greatest actor of all time. Brando rolls his eyes. “See, that’s a part of the sickness in America,” he says, “that you have to think in terms of who wins, who loses. Who’s good, who’s bad, who’s best, who’s worst.” Acerbic wit aside, Reverb isn’t a superlative. He’s the average sort, perhaps a bit below average in some ways, someone Arthur Miller might’ve taken a shine to. In his best play, Death of a Salesman, perhaps the best of all American dramas, he demonstrates that tragedy doesn’t require a king or a celebrated hero. (Willy Loman’s last name is no accident.) “A small man can be just as exhausted as a great man,” Linda, Willy’s wife, points out. Similarly, the events in Fine imply that talent, brilliance, and beauty, among other coveted traits, aren’t sine qua nons for happiness.

If you go ahead and pick up a copy of Fine, the worst that’s likely to happen is that some sentence, no matter the page, will make you laugh or giggle or chortle. The best? You get the laughs and, after turning the last page, you’ll find yourself just a smidge more reconciled to one day becoming Aunt Sylvia.

Vincent Czyz is the author of a collection of short fiction, which won the Eric Hoffer Award for Best in Small Press, two novels, a novella, and an essay collection. Czyz is the recipient of two fiction fellowships from the NJ Council on the Arts, the W. Faulkner-W. Wisdom Prize for Short Fiction, and the Capote Fellowship at Rutgers University. He has placed stories in Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Southern Indiana Review, Tampa Review, Georgetown Review, Tin House, and Copper Nickel, among other publications.