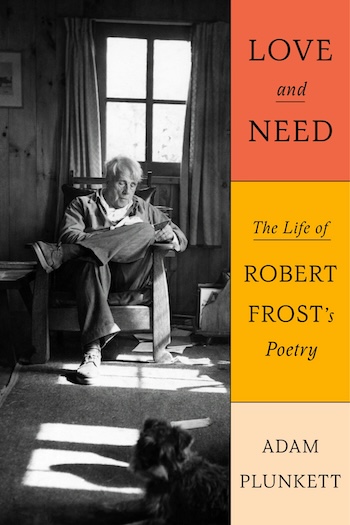

Book Review: “Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry” — Into a New Clearing

By James Provencher

Besides giving us a multi-faceted portrait of Robert Frost that leaves the poet tantalizingly inscrutable, Adam Plunkett does what the best biographers of great writers do: send us back to the work with renewed curiosity and heightened appreciation.

Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry by Adam Plunkett. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 512 pages, $37.

Why another Robert Frost biography? One hundred and fifty years since his birth, surely by now this elusive force of nature has been pinned down and found out. There’s been a spate of fond memoirs, revering reminiscences, and naïve, well-intentioned life portraits. Most of these are reflective of Frost’s tendency to publicly project a self-mythologized persona.

Why another Robert Frost biography? One hundred and fifty years since his birth, surely by now this elusive force of nature has been pinned down and found out. There’s been a spate of fond memoirs, revering reminiscences, and naïve, well-intentioned life portraits. Most of these are reflective of Frost’s tendency to publicly project a self-mythologized persona.

Early on, Frost announced that, as a poet, he was going to reach out to all kinds. Like Longfellow, he would seek and ultimately find a wide, popular audience. Over the years his critical reputation would suffer from his so-called pandering to the crowd. High Modernist critics, whom Frost dubbed the ‘Eliot Gang,’ dismissed the good, gray poet-jester persona as a regional rhymester, a common-folk farmer, a wise-cracking pundit, a winking, sentimental sage. The man behind the mask, of course, was nothing of the sort; and even his wife Elinor called him out. In fact, Frost suggested, after her death, that she resented his “barding around”. She wished his poetry had remained only between themselves. After Frost’s death, by prior agreement, arrived ‘official biographer’ Lawrance Thompson’s three-volumed ‘Monster-Myth’, which demonized the poet as some kind of mean-spirited, vengeful villain. It took decades and three late twentieth century revisionist biographies to redress that image, redeeming Frost as an all-too-human figure who suffered much tragedy. Yes, had his flaws, but he was both a good poet and a good man.

In his definitive critical-biographical study, Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry, Adam Plunkett asserts that the man and his work, Frost and his poetry, are one. It’s as if Frost made a crossroads pact with the Muses, not just to make poetry, but to also live poetically. That choice made all the difference, and to this day it profoundly challenges any aspiring biographer. Plunkett meets this head on, deftly teasing out Frost’s contradictions, navigating his dark woods and desert places, patiently tracing his ambiguous designs. Plunkett proves only a consolidating, two-pronged approach, both critical and biographical, can hope to encompass such an elusive, complex, and enigmatic artist who lives his art. And this study, building on earlier revisionist portraits, succeeds in bringing a vitally whole Frost into a new clearing. By so doing, Plunkett restores the wonder of Frost’s initial mystery as poet and person, his beguiling talk-song reverie, his otherworldly spell-casting.

The title, Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry, clearly signals Plunkett’s strategic approach and modus operandi. ‘Love and Need’ comes from a poem in A Further Range, ‘Two Tramps in Mud Time.’ Frost’s farmer speaker is splitting wood when two Depression-era tramps happen by, looking for work. Yet for Frost, the common chore is serious play, done for need, granted, but also for love — just for the sheer morning gladness of it. For the poet, delivering measured blows is a kind of poetry. We are provided an example of that when he refuses to surrender his task to the passersby: “My object in living is to unite/My avocation and my vocation/as my eyes make one in sight./Only where love and need are one,/And the work is play for mortal stakes/Is the deed ever really done/For Heaven and the future’s sakes”. This is Frost in a nutshell, to the core, a succinct statement of his aesthetic and Plunkett’s thesis. Here Frost dovetails pragmatism and philosophical elan vital in the play of opposites, the juggling of paradoxical elements: work and play, life and work, are one. And note that part of what the poem is doing is offering a rejoinder to the tramps. This emphasis on conversation, its natural dramatic tension and vernacular sound of sense, would infuse Frost’s poetry over a lifetime. Throughout Love and Need, Plunkett traces how poems are kindled and sparked to life by actual, lived experience.

Plunkett’s aptly phrased sub-title, The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry, is just as telling. A curious way to put it, “The Life…of Poetry”. In this way, the biographer underlines his holistic method. Frost’s poetry was a way of life; the life, the way of poetry. That approach helps explain why this critical-biography has such narrative drive. Biographer Jay Parini introduced his 1996 portrait, Robert Frost: A Life with this sentiment: ‘Every literary biography requires something in common with novels — a good story.” Plunket makes the most out of the last third of Frost’s life by configuring it as a strange, ripping tale, a mystery-potboiler. The opening chapter kicks off in medias res, setting up the suspense before flashing back to serve up a melodramatic, scandalous backstory. There are three great spheres in life, Frost once wryly observed: Science, Religion, and Gossip. Gossip, here, of course, another name for Literature.

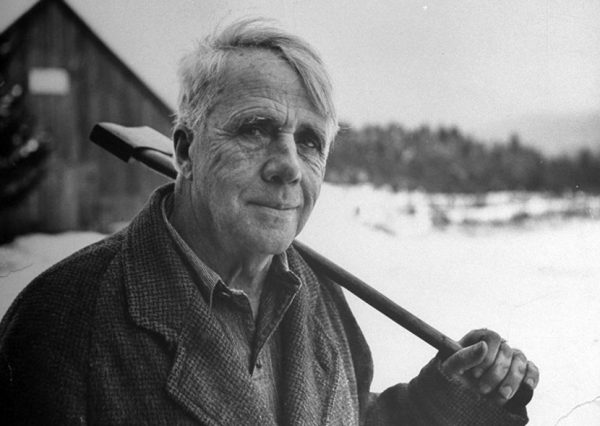

Robert Frost — Adam Plunkett argues that he was both a good poet and a good man. Photo: Wiki Commons

The gossip begins in 1938, with Elinor’s sudden death in Gainesville, Florida, where the Frosts were snowbirds, wintering out. The poet is rocked by his wife’s death. At sea, rudderless, unmoored and bereft, he plunges into a dark, unstable period. Alone and vulnerable, he falls deeply in love with his married secretary, Kay Morrison. Kay treats this affair as more of a tryst or fling, but Frost pursues her possessively, relentlessly. He, 64 and she, 39.

Aside from making good use of Frost’s potboiler of a personal life, Plunkett also tackles whether the poet believed in God. Elinor, a non-believer, always chided her husband for ‘wanting to have it both ways’: being Doubter and Believer. Frost teasingly mocked T.S. Eliot, a lifelong rival of sorts, for his faith: ‘He plays Eucharist while I play Euchre!’ When asked once if he would ever submit to Freudian analysis, Frost shot back that he would never think to shine a light into his dark corners. He wished to remain an enigma to himself.

Besides giving us a multi-faceted portrait of Frost that leaves the poet tantalizingly inscrutable, Plunkett does what the best biographers of great writers do: send us back to the work with renewed curiosity and heightened appreciation. In this case, not just back to his poems, but to the germinating milieus and landscapes that shaped Frost’s verse.

Robert Frost’s Farm in Derry, New Hampshire. Photo: Frost Farm

Backroading one March afternoon, I happened on Frost’s New Hampshire Derry farm, his Walden. Swollen by snowmelt, Hyla Brook was there, still west-running, against the grain. The wall he did and did not love still stood, despite frost heaves reaching up from the ground. His cellar, the root-cellar, with door ajar, exhaled a cold and wintry breath. Bare kitchen floorboards froze despite a shimmering March sun while snow blossoms rimed the apple trees. I stared into the farmhouse, my hands cupped against the glass to catch a trace of the poet. No glimpse — only sensations of a drop in temperature and birches clicking out a Northern Code. The sight of a snowy mane receding on a hill. Frost — there and not there.

James Provencher, a U.S. Ex-pat living in Canberra, Australia, is a former Teacher/Poet in Residence at The Frost Place, Robert Frost’s farm and museum in Franconia, NH.

Jimmy Pro waxes cool on one America’s greatest poets. You had to be there observing to spit out this good stuff! A prosaic ode to Bobby Frost. An example of the road well taken by the reviewer.

Jim, thanks for a refreshing take on this new Robert Frost bio. It seems high time for a “consolidating, two-pronged approach, both critical and biographical” on the poet. Thankfully he was able to escape the big LABEL WRITER that tends to stamp out identities for our artists, easy tags that stick and can last for (and often shorten) a creative lifetime. Poe managed to escape the tar that Rufus Griswold slathered on him post mortem. Twain, too, eventually got out from being branded a humorist; it’s not that he wasn’t a funny-ass bastard, he was. But he was also much more. Like Poe and Frost he was multi-faceted, which is part of why they endure. Good review; it makes me want to read Plunkett’s book.