Book Review: “Louis B. Mayer & Irving Thalberg: The Whole Equation” — More of the Same

By Gerald Peary

At some point during the writing of the book, Ken Turan must have realized, sadly, that the Mayer/Thalberg/MGM story has been done to death. All he could do was what he did: tell well what had been told well before.

Louis B. Mayer & Irving Thalberg: The Whole Equation by Ken Turan. Yale University Press, Jewish Lives Series, 392 pages, $30.

It was New York Times critic Bosley Crowther who started the flood of books about Hollywood’s most successful and affluent studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer — “More Stars Than There are in Heaven” MGM — and about the two men, Louis B. Mayer and Irving G. Thalberg, who ran the studio in its 1920s and 1930s Golden Era. Crowther published The Lion’s Share: The Story of an Entertainment Empire in 1957 and Hollywood: The Life and Times of Louis B. Mayer in 1960. After that came the Metro deluge. Easily a dozen volumes chronicled MGM under the reigns of Louis B. and Irving F., from Gary Carey’s 1981 All the Stars in Heaven: Louis B. Mayer’s MGM to Mark A. Vieira’s Irving Thalberg: Boy Wonder to Producer in 2010. Lots of thoughtful books by knowledgeable writers.

Louis B. Mayer & Irving Thalberg: The Whole Equation by Kenneth Turan, the retired chief film critic for the Los Angeles Times, is the newest attempt to elucidate what was going on at MGM under the Mayer/Thalberg thumb. With Turan, we are in the hands of a trusted film historian. The book is definitely a good read and, for most readers, all you’d need to know about the doings at MGM. But “The Whole Equation” in the subtitle is also a warning for the very few who demand more, crave more, than what has appeared in the many other books. Because, despite Turan’s deep-dive of library files and uncovering of unpublished letters and memoirs and scouring of dozens of published memoirs by actors, directors, and screenwriters with MGM recollections, the finished book isn’t significantly different from what has come before. This is not a revisionist history. What you thought about Mayer and Thalberg and MGM prior to Turan will probably be intensified, not challenged.

I don’t think this is Turan’s fault. For this commissioned work for Yale University Press’s Jewish Lives series, he certainly did his research. But at some point while writing the book he must have realized, sadly, that the Mayer/Thalberg/MGM story has been done to death. All Turan could do was what he did: tell well what had been told well before.

So here I go too, reiterating the much-reported tale of the unlikely partnership of two 20th-century motion picture giants with little in common except their being Jewish mama’s boys (which fed their considerable egos), and having a delirious love of movies and movie-making. And unstoppable, unwavering wills to succeed.

Mayer arrived in Hollywood by the most circuitous path imaginable, a child of an impoverished refugee family from Eastern Europe, then a teenage scrap metal dealer in New Brunswick, Canada, then a movie theater owner in Haverhill, Massachusetts, then buying into a distribution company called Metro Pictures. And then, still in the East, producing films himself by doing what he’d become a master at, courting and luring stars, in this case Francis X. Bushman and Anita Stewart. Around 1918, he ventured to LA and rented a cheap studio space near the Selig Zoo. Mayer announced in a prophetic telegraph message, “My unchanging policy will be great star, great director, great play, great cast.” Nobody could ever argue “…great star…great cast.”

Irving Thalberg at his desk in 1927. MGM publicity photo

Irving Thalberg started worse, but had an extraordinarily easier time achieving movie industry power. He was born in New York City with a congenitally defective heart which, during his glory Hollywood days, would sicken him often and lead to his very early death at 37. In his early years, though, he was a pampered bourgeois: his family were prosperous German Jews, his father owned a department store. At age 19, he became the personal secretary of Universal head Carl Laemmle, in Laemmle’s New York office. Says Turan, “Finding Thalberg an invaluable organizer, Laemmle made a spur-of-the-moment decision in 1919 to take his young employee with him first to Chicago and then Los Angeles.” A pale and frail 21-year-old Hollywood executive, this Little Lord Fauntleroy became the subject of many anecdotes in which he was mistaken for a teen office boy. But once people caught on to his precocious abilities, a new appellative emerged — “Boy Wonder.”

All of Hollywood talked about this baby-faced lad when he showed the daring to fire the intimidating Erich von Stroheim for going extravagantly over budget directing Merry Go Round. Soon afterward, in 1923, he became a vice president at Louis B. Mayer Studios. Mayer was the father of two daughters; he took to Thalberg as the Jewish son he never had. Together, they would move to the top as MGM grew to maturity and Leo the Lion roared with success. Mayer was head of the studio, in charge of all financial matters and of the hiring of actors and directors. Thalberg was the head of production, including the employment of screenwriters and the overseeing of screenplays. It was in administering these jobs that the once-boy wonder became far more revered, even legendary (Monroe Stahr in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon) as a “genius.” That was the term in the press: “genius.” Thalberg seemed comfortable with it.

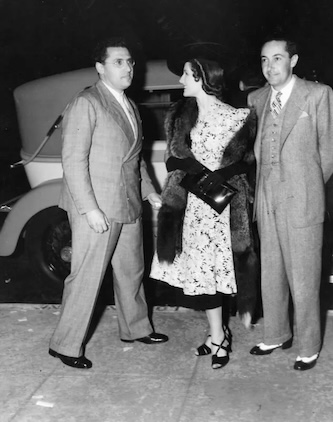

George Cukor, Norma Shearer, and Irving Thalberg in 1936.

Was it deserved? Actor Rod La Rocque said, “Thalberg had an innate understanding of tempo, timing, character, philosophy, psychology,” and director George Cukor said approvingly of Thalberg, “In his own way he was an artist himself.… He wouldn’t stop until he felt everything was as good as it could possibly be.” And here’s a place where Turan’s assiduous research paid off well: he uncovered the text of four months of story conferences around the making of the 1932 MGM hit Grand Hotel. Turan evaluated what he read and concluded, “Thalberg comes off as exceptionally detail oriented, willing to go over the script line by line and, in later conferences, footage almost angle by angle.… It’s clear that Thalberg lived for the ins and outs of sentence structure and story construction in a way that was unexpected for an executive.”

And let’s not forget Mayer, who all this time was building with his business acumen the richest and most powerful studio by far and, as advertised, the one with the most dazzling actors and actresses on long-term contracts: in silent days, Joan Crawford and Norma Shearer (Thalberg’s wife) and John Gilbert and Sweden’s Greta Garbo, who’d make every one of her American films at MGM. And then: Marie Dressler, Wallace Beery, Clark Gable, the three sibling Barrymores. Katharine Hepburn was huffy and difficult but not in her adoration for her MGM boss Mayer. Said Mayer’s grandson, Danny Selznick, “He adored movies with a relish that, I suspect, may have been unique. I mean, I wonder whether Jack Warner or Harry Cohn … [took] the incredible pleasure he took in the movies he made.”

Mayer was guided totally by his emotions. He cried easily and melodramatically. He could be warm and friendly yet also truly frightening when his temper exploded. Thalberg was cautiously amicable, especially with screenwriters. Charles MacArthur, The Front Page co-author, was his best friend. But most people described the producer as icy and aloof, and he was infamous for keeping others, star actors especially, waiting for hours outside of his office for a scheduled appointment. But no worries once you finally got in, at least not sexual worries. During the ’30s, neither of the two big cheeses at MGM maintained a casting couch. Both Thalberg and Mayer were strict moralists, seemingly faithful married men who had a father (Mayer) and a mother (Thalberg) residing with them and who sincerely believed in family values. Especially on screen.

And here is the start of my problem with MGM studios. It’s fun to read of Mayer’s sanctification of mothers and his adulation of the family, but not so much fun when faced with watching those cloying, sentimental MGM movies. And, yes, Thalberg loved writers but he juggled them around so much that three or more could share credits on a film. All that script talent was homogenized into what often became a bland Hollywood product. Also Thalberg’s stalwart championing of writers stopped dead with his and Mayer’s hostile opposition to the organizing of the Screen Writers Guild. “We live in paradise,” Thalberg complained. “It’s going to be destroyed by organized labor.”

Thalberg and Louis B. Mayer. MGM publicity photo

And here is also where I wanted more from Kenneth Turan, his weighing in on the undeniable: that, looked at many decades later, the MGM movies of the ’30s, despite their glamorous stars and the extravagant settings and décor, are, as a whole, the least interesting of any from the major studies. They are certainly below in worth what was released by Warners, Paramount, and RKO — despite Mayer’s financial wizardry and Thalberg’s “genius.”

In my view, Mayer was a low-brow and Thalberg a middle-brow and that’s a lethal combination for artistically meaningful cinema. How truly unusual at MGM for Thalberg to have greenlighted King Vidor’s expressionist and avant-garde The Crowd (1928) or for Mayer to allow production of Fritz Lang’s heated and pessimistic Fury (1936). Normally, the duo made safe and sugary movies which they felt sure audiences would pay for. It was Thalberg who initiated in Hollywood the dreaded-by-directors “sneak previews.” Newly finished MGM movies were tried out in the L.A. burbs, then alterations were made dictated by audience response.

The biggest fault with MGM movies was, in the pre-Vincente Minnelli ’30s, how impersonally and uninterestingly they were directed. Mayer and Thalberg wanted anything but visionary auteurs. They placed behind the camera competent but formally indifferent filmmakers like Victor Fleming and W.S. Van Dyke, whose greatest skill was that they shot quickly and on budget. I wish Turan had explained how Clarence Brown, MGM’s most sensitive and visually attuned director, had gotten by in his many years in residence. What strategy did Cukor, an excellent director, use coming in and out of the studio? And how did the great visual stylist Ernst Lubitsch, so at home at Paramount, maneuver his way at MGM for The Merry Widow (1934) and Ninotchka (1939)?

These might be starting questions for the next book on Mayer/Thalberg/MGM, which I don’t doubt is being incubated as I write.

Gerald Peary is a professor emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His last documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, played at film festivals around the world, and is available for free on YouTube. His latest book, Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, was published by the University Press of Kentucky. With Amy Geller, he is the co-creator and co-host of a seven-episode podcast, The Rabbis Go South, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Thanks, Gerry. You saved me from having to read any of these books! And I learned a few things I did not know. A beautifully told review. Funny, I thought Mayer was a casting-couch guy. I guess I’ve got him confused with the many others Norma Shearer said she had to fuck (her word).

Thanks for the kind words on my review. In later years after his wife died, Mayer started getting a bit randy, having starlets sit on his lap, supposedly pawing Judy Garland on one occasion. I don’t think he was doing these things in the ’30s. I don’t know where you read that Norma Shearer said she had to fuck all these guys. That seems totally wrong. But find the quote and educate me.