Arts Commentary: Candy Rappers of 2024 — Remembering Candy Darling

By Trevor Fairbrother

It is clear to Candy Darling’s biographer that the present moment contains alarming reminders of the political scapegoating generated by the culture wars of the ’90s. She leaves no doubt that her subject’s difficult, complicated life embodies a cautionary tale.

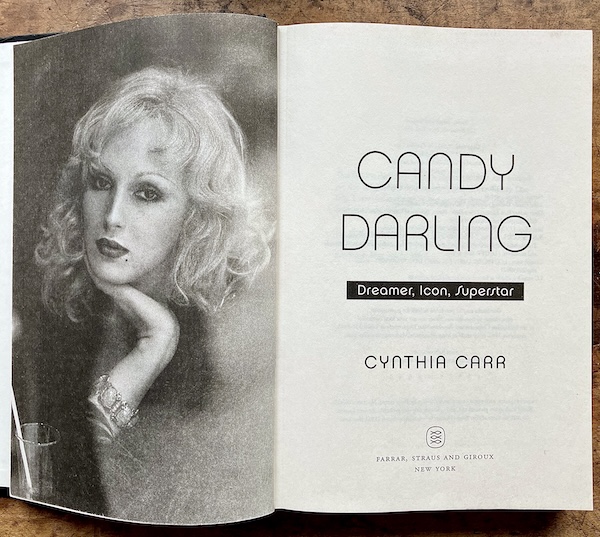

Cynthia Carr’s 2024 book Candy Darling, undated frontispiece image by Peter Beard. Photo: Trevor Fairbrother

Candy Darling (1944-1974) had a tremendous influence on the bohemian subculture of New York as an actress in Off-Off-Broadway theater and a collaborator in several of Andy Warhol’s enterprises. 2024 was a banner year for her legacy. Last March saw the publication of a widely acclaimed book by Cynthia Carr: Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar. Hilton Als, the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic, author, and curator, hailed it as a “monumental biography” of a “brilliantly constructed persona,” and declared, “I can’t imagine a better or more honest writer for the task.” (The New Yorker)

This essay looks at Carr’s participation in four public programs in Manhattan last year, all accessible on YouTube. In March Kate Bornstein interviewed her at The Rizzoli Bookstore on Broadway. Carr noted that her procedure in writing the biography was to stay mindful of “What would Candy want?” She thanked Bornstein for having been one of 10 people in the trans community who helped her decide on a strategy for personal pronouns. Bornstein, whose book Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women, and the Rest of Us was published in 1994, identifies as non-binary and uses the pronouns they/them and she/her. Carr decided that she, as author, would always refer to her subject as Candy and would not change the language used by family and early friends. Candy had been named James Lawrence Slattery and was known as “he” and “Jimmy” during her childhood and her years as a tortured effeminate boy desperate to get out of school.

Candy Darling in a scene from 1971’s Women in Revolt.

Bornstein asked Carr if she’d been surprised by anything in the course of her research and two stories were told. The first centered on the fact that 10 of Darling’s teeth fell out when she was 18. This proved an abiding complication because she could not afford good dentistry and relied on well-wishers to pay for caps. Second, Carr described surprising information about Darling’s spiritual and metaphysical approaches to religion. Raised Catholic, she knew she was an outcast. The Christian Science writings of Mary Baker Eddy made her wonder if she might use her mind to will a body of a different sex. In the early ’70s she took an interest in Guru Maharaj Ji.

Carr conducted an interview with Lucy Sante at the New York Society Library on East 79th Street in June 2024. Sante had transitioned from being a man (Luc) in 2021, and was promoting her new memoir I Heard Her Call My Name. Carr asked her to talk about the fact that, by the age of 10, Luc had realized he was female, but repressed that secret for decades. Lucy admitted that she had never identified with males, but now, as a woman of 70, she experiences an ongoing self-interrogation and has to deal with feelings that she is a fraud. Carr remarked that “coming out to yourself” is often the hardest step in recognizing one’s sexual and gender orientations, then added, “I’m a lesbian. I’m not feminine. I’m not the right sort of woman … but I don’t worry about it.”

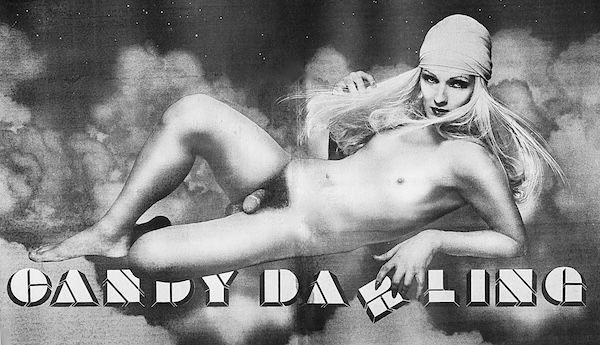

A detail of Richard Bernstein’s Candy Darling from the October 1969 issue of Newspaper. Image from The Yale Review. Courtesy Primary Information and The Estate of Richard Bernstein

It was inevitable that Candy Darling would be a mutual point of reference and they discussed a 1969 montage by Richard Bernstein presenting Candy undressed in a recumbent pose echoing Michelangelo’s Adam. It was, in fact, an amalgamation of photographs, probably of three different people: Candy’s nude upper body and her small breasts; an anonymous (female?) lower body; and an anonymous penis. This gender-bending provocation debuted in the October 1969 issue of Newspaper, a new pictures-only “alternative” periodical published by downtown artists. Bernstein then developed it as a limited-edition color lithograph, which is illustrated in Candy Darling. Evidently Lucy Sante encountered the image there for the first time, and she told Carr she would have been deeply shaken if she’d seen it back in the day.

In April 2024 Mx. Justin Vivian Bond interviewed Carr at The Bureau of General Services—Queer Division, the bookstore at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center on West 13th St. Bond, a transgender singer-songwriter, actor, and queer rights activist, deftly folded the political into the conversation, echoing, in the most positive sense, the late-’60s slogan “The personal is political.” Carr agreed with Bond that Darling did not evolve in her thinking regarding the propulsive feminist movement. One putatively worst-case scenario was her response to “A Dialogue on Women’s Liberation” at New York’s Town Hall in 1971. Norman Mailer spoke with four feminist advocates including the “out” lesbian, Jill Johnson, who began her career as dance critic for The Village Voice. When Mailer cut off Johnson’s presentation, claiming she’d exceeded the allotted time, two women from the audience boisterously hugged Johnson; then Mailer said “C’mon, Jill, be a lady.” Bob Colacello, the editor of Warhol’s monthly publication Interview, accompanied Candy to the event and claimed that his friend was appalled by the unladylike antics.

The discussion between Bond and Carr circled the fraught complexity of Darling’s situation. She lived from hand to mouth, never had a place of her own, and constantly faced prejudice and hostility. Her father was an abusive drunk addicted to gambling. Her mother accepted her female identity in private, but lived in constant fear of being shamed by the neighbors. Bond noted that Candy may have had a few famous “guardian angels” who occasionally eased her difficult life — notably Warhol and Tennessee Williams — but they too were victimized in the homophobic mainstream culture. Darling disliked Warhol’s references to her as a drag queen, but survival was her priority and he was her best shot at fame.

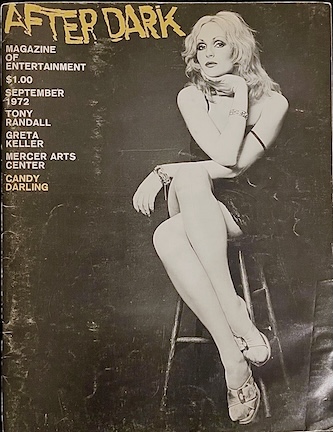

The September 1972 issue of After Dark featuring a photograph by Jack Mitchell. Image: Ebay.

In October 2024 Lucy Sante interviewed Carr at the CUNY Graduate Center on Fifth Avenue. The discussion circled Candy Darling’s many contradictions as a “superstar” whose goal was to lead a resurgence of old-style glamour in Hollywood. While making waves at the cutting-edge of the downtown scene, she supported U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. The paradoxes persisted at her memorial service at the swanky Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel on the Upper East Side: it was a mystery who paid for the funeral expenses; Candy’s parents were incensed that the obituary in Newsday included an homage from Candy’s friend Danny Fields saying that she far outshone the typical drag queens; Candy’s father was disgusted that the corpse wore a high-necked gown decorated by rhinestones. An anonymous patron (Jacquie Collins) ordered funeral cards with the name Candy Darling and the father demanded that the funeral directors also print cards with the name James L. Slattery and give guests a choice of cards. (Most attendees took the “Candy” cards.)

Today’s young people may naively imagine that Candy’s luminous mystique was attained with preordained ease. But the potent, uninhibited aura she presented in person was painstakingly crafted by a singularly brave, tireless, and resourceful individualist. In her book and these interviews Carr grants that Darling did some things that were “not so nice” — from youthful petty thieving to outbursts of malicious self-importance during her diva days. Nonetheless, she generously stands by the bigger picture: Candy had many admirable qualities and she was far from stupid. For me, the most pointed reflection on this milieu is Warhol’s sly and easily misunderstood satire Women in Revolt (1971), a film in which Candy co-starred with two other genderqueer downtown celebutantes, Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn. The following year Lou Reed namechecked that trio in his Glam Rock torch song “Walk on the Wild Side.”

Carr dedicates Candy Darling to the trans community with these invocations: “May this account of one life make a difference. May you be understood. May you be appreciated. May you be loved.” It is clear to Darling’s biographer that the present moment contains alarming reminders of the political scapegoating generated by the culture wars of the ’90s. She leaves no doubt that her subject’s difficult, complicated life embodies a cautionary tale.

Trevor Fairbrother is a writer and curator. He still thanks his lucky stars that in 1995 he successfully persuaded the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to acquire Catherine Opie’s Vaginal Davis and Lyle Ashton Harris’s Miss America

© Fairbrother 2025

Tagged: "I Heard Her Call My Name", Andy-Warhol, Candy Darling, Cynthia Carr, Kate Bornstein, Lucy Sante, trans community

A shout-out to Cynthia Carr. Her book Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar just received the 2024 Award for Biography from the National Book Critics Circle at a ceremony at the New School in New York City.

I love that Fairbrother built such an appealing article on a series of interviews available on YouTube. One correction: director Paul Morrissey, who died several months ago, is no doubt bursting with anger in his grave that once again one of his films, Women in Revolt, perhaps his best one, is attributed to Andy Warhol and not to him. The erudite writer should have picked this up, as well as whoever edited this piece.

I am far from an expert.

But, according to the AI-powered search engine, Perplexity, which includes sources for its responses:

“There is some ambiguity regarding the direction of Women in Revolt. While Paul Morrissey is widely credited as the director, including in official records and film databases, disputes have arisen over Andy Warhol’s involvement in the film.

Film scholar J. Hoberman noted that Morrissey secured the rights to Women in Revolt through an agreement with the Warhol Foundation, but also highlighted Warhol’s significant involvement in the production. Jackie Curtis, one of the film’s stars, claimed in a 1978 interview that Warhol directed her scenes, asserting that she only participated because Warhol was behind the camera. However, co-star Holly Woodlawn refuted this claim in her autobiography, stating that Warhol never operated the camera and that Morrissey maintained control.

Additionally, discussions about Morrissey’s conservative political views and Warhol’s broader creative influence suggest tensions between their artistic visions. Despite these disputes, Morrissey remains officially credited as the director.”

Thanks for your good words. You are right to speak up for Paul Morrissey. I framed Women in Revolt as a Warholian product and purposely did not name a director. A 1972 review in the San Francisco Examiner had these credits: “Directed by Andy Warhol; executive producer Paul Morrissey; produced by Andy Warhol Films, Inc.” Warhol invited Morrissey to work for his “Factory” collective in 1965, eager to see if his avant-garde films might benefit from an acolyte with technical skills. Morrissey acknowledged that they leveraged Warhol’s notoriety to stimulate interest: “Andy is a producer of films; he’s a film studio, [like] MGM, Walt Disney, Paramount. … He never ever said he was a director, and Andy’s name appeared as director of the films because I put it there.” (Studio International, February 1971). Morrissey and Warhol parted ways in 1974.