Film Reviews: At DOC NYC — Scenes of Crimes

By David D’Arcy

Interviews with a pillager – “Plunderer” examines Nazi art theft at DOC NYC; two other docs remember Artsakh, a country that is no more

A scene from Hugo Macgregor’s Plunderer. Photo: DOC NYC

Plunderer, directed by Hugo Macgregor, is a study of a Nazi art historian-turned-dealer who looted art and got rich selling it — even richer after the war. The film broadens into a look at the theft of hundreds of thousands of works of art from Jews. Many of those Jews were murdered.

In case you’re already wondering, this ruthless art theft, engineered teams of aesthetes trained in art history, overlapped with some of the worst horrors of the Holocaust. To its credit, this film stresses that Nazi art crimes were not just about stealing pretty paintings.

Plunderer follows the historian Jonathan Petropoulos, a veteran in the study of Nazi cultural crimes, as he reconstructs his interactions with Bruno Lohse (1911-2007), an SS-man man with elegant manners and a doctorate who was charged with acquiring art for Nazi leaders, particularly Hermann Göring, the much-larger-than-life Hitler crony from the party’s early days who became head of the Luftwaffe.

Petropoulos, who had access to papers that Lohse left behind, has written extensively about Nazi plundering, and provided expert testimony in court cases focused on restitution. He is rare in his field for having met his subject, Lohse, whose closeness to Göring meant that he had a car and carte blanche to buy pictures or to pry them out of Jewish hands. The urbane man’s prying could be coercive, very coercive. After the war and, after repeated interrogations, detention, and a surprise acquittal on crimes against French culture in a French court, Lohse reinvented himself, as the saying goes, resuming his activities as a suave middleman in art deals that rarely bore his signature.

Munich after the war was full of ex-Nazis, a fitting place for such a vocation, we are told, especially if you were a Nazi. It was a small place where everybody knew each other and, as investigator Willi Korte notes in Plundered, it had become even smaller because Jewish dealers and collectors had been driven out or murdered, leaving their art behind. Lohse reconstructed his reputation, one client at a time, guiding purchases of works looted from Jews and helping Germans (including families of ex-Nazi leaders) recover their treasures. “What brought them together was their appreciation for certain works of art, and the rest didn’t matter,” Korte notes. New clients, if they ever knew or suspected the past of the man decorated by Hitler for his art crimes, were drawn in by the opportunities he provided to acquire works of art. Those clients included museums in the United States, where the money was in those days.

We are given extensive context from veteran researchers of Nazi art crimes, which makes Plunderer a useful introduction to the collusive network that enabled art crimes of that era and its aftermath, when museums and “respectable” collectors benefited from Lohse’s first-hand experience and access.

Of course, dealing with Lohse wasn’t just about fine wines and connoisseurship. The SS-man was adept at hiring thugs to get the paintings he sought in wartime France. Petropoulos also notes that he had a role in prying precious paintings out of the hands of the German-born collector Friedrich Gutmann, who was murdered by Nazis in a prison in Czechoslovakia. Gutmann’s wife was sent to her death in Auschwitz. Their grandson, Simon Goodman, talks about seeing a painting from the family collection, which they sold under duress, in the San Diego Museum of Art.

Of course, dealing with Lohse wasn’t just about fine wines and connoisseurship. The SS-man was adept at hiring thugs to get the paintings he sought in wartime France. Petropoulos also notes that he had a role in prying precious paintings out of the hands of the German-born collector Friedrich Gutmann, who was murdered by Nazis in a prison in Czechoslovakia. Gutmann’s wife was sent to her death in Auschwitz. Their grandson, Simon Goodman, talks about seeing a painting from the family collection, which they sold under duress, in the San Diego Museum of Art.

Plunderer tracks other looted works, some tossed into the oubliettes of Swiss galleries, where plenty of Nazi-looted art ended up. Often that work, designated as “degenerate art,” sold for hard currency. Some works were parked in Swiss bank vaults before buyers were found. Some are still there, say insiders who note that a Swiss art gallery may be harder to penetrate than a Swiss bank

Allied investigators like Douglas Cooper, a friend of Picasso (and former lover of Picasso’s biographer, John Richardson), were wise to Lohse and his dealer colleagues. But some Monuments Men warmed to him. The film reminds us that cronies in the small and clubby art world protected each other. The film also notes some of Lohse’s deals in the US, but becomes sketchy when it comes to supplying details of how pictures that Lohse provided got there and how much the museum people knew. Some US curators were Lohse’s chums. We don’t hear any evidence that curators or collectors at the time were deterred by questionable provenances — not that museum people discussed that issue back then. What’s clear is that the more one learns about Lohse, the quicker the charm he deployed on first encounters wears thin. Still, buyers were so eager to get what he was selling that they never looked too hard at where it might have come from.

Plunderer does not give us much more than a picture or two and a few scratchy quotes in Lohse’s voice – in German – so the doc relies mostly on testimony from experts who have a lot to say, especially for an audience coming to this subject for the first time.

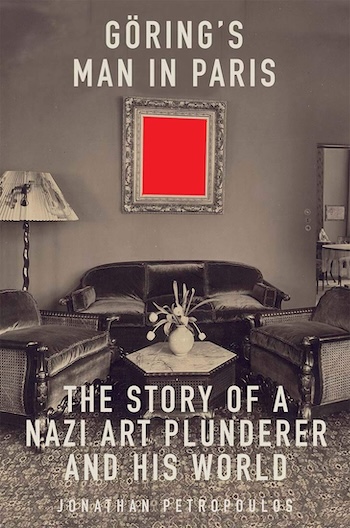

The result is that we are given valuable information but not much cinema. For those who are interested, a lot more about the Nazis’ vast art theft operation can be gleaned from Petropoulos’ Göring’s Man in Paris: The Story of a Nazi Art Plunderer and His World (Yale University Press), which was published in 2021.

Plunderer plays on PBS early next year – time enough to read the book.

A scene from There Was, There Was Not. Photo: DOC NYC

Also at DOC NYC were two films set in Artsakh (also called Nagorno Karabakh, an independent region linked to Armenia) that neighboring Azerbaijan last year emptied of its Armenian population. Artsakh is now part of Azerbaijan. In this era of brutal displacements of people, did anyone notice?

The mainstream media did, for a moment. Two new docs look at the Armenian side of the resolution, if we can call it that, of a long dispute — ethnic cleansing, pure and simple.

Emily Mkrtichian’s There Was, There Was Not was begun in 2019 and pivoted when Azerbaijan invaded Artsakh and overran the region at the end of 2023. The title is a translation from the first line of Armenian fairy tales, their version of “once upon a time.” The director observes, from a distance, the trauma of displacement as seen by women, looking at how cataclysm shapes the rhythms of everyday life and much more. This is not a film from the front. Mkrtichian concentrates on the effects of war on noncombatants – women and children in this case – although some women are armed and in uniform. The landscape — gentle and serene, sometimes rugged, sometimes shrouded in the smoke of war — becomes a backdrop for a new, heartbreaking reality as most Armenians flee.

A scene from My Sweet Land. Photo: courtesy of HAI Creative, Sister Productions, and Soilsiú Films

My Sweet Land by Sareen Hairabedian looks at children in a village not far from the front as they dream of what they might be when they grow up. The war is close enough to be heard, but too far away for the very young to understand it. The 1952 classic Forbidden Games by Rene Clement comes to mind. Once again, the landscape of Artsakh plays a hypnotic role.

An international co-production from Ireland, France, Jordan, and the US, My Sweet Land was Jordan’s nominee for this year’s International Academy Award. That’s a rare honor for any doc, but it was withdrawn by Jordan when Azerbaijan disapproved and lodged an official complaint to Amman. Jordan withdrew the nomination. It wasn’t enough to win the war on the ground and drive Armenians out of Artsakh. The next step: mounting a war on memory, which included blocking any hope of recognition from Hollywood.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: "Goering's Man in Paris: The Story of a Nazi Art Plunderer and His World”, "My Sweet Land", "Plunderer", "The Was There Was Not", Artsakh, Hugo Macgregor, Jonathan Petropoulos

I have not read Jonathan Petropoulos’ Göring’s Man in Paris: The Story of a Nazi Art Plunderer and His World, but I will. I would highly recommend his 2000 book The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany, which includes chapters on artists, art dealers, arts historians, art museum directors and, best of all, the era’s venial cadre of arts journalists. “The career of an art critic in Nazi Germany was distinguished from those in other art professions in that it required an even great degree of collaboration with the regime.”

The presentation of such documentaries is important for exploring the darker pages of cultural history. Plunderer, by shedding light on Nazi art theft and cultural crimes during the Holocaust, highlights a crucial and often overlooked aspect of World War II.

However, it is regrettable that the other two films mentioned in the article — There Was, There Was Not and My Sweet Land — offer a one-sided portrayal of events related to Nagorno-Karabakh, a region internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan. These films omit essential facts, such as Armenia’s nearly 30-year-long occupation of Azerbaijani territories and the displacement of around one million Azerbaijanis from their homes during that period.

The 44-day war in 2020 and the local anti-terror measures in 2023 allowed Azerbaijan to restore its territorial integrity in line with international law and UN Security Council resolutions.

When films presented as documentaries promote a selective and politicized narrative while ignoring the broader historical and legal context, it raises serious concerns. Showing only one side of the truth undermines the integrity of documentary filmmaking and contradicts the principles of objective journalism.