Book Review: “Unit 29” — The Voices of the Incarcerated

By Bill Littlefield

An argument for this collection might be that anything anyone writes from prison should be published, since whatever it is, it will inform readers regarding the grim circumstances about two million of our fellow citizens endure everyday, day after day.

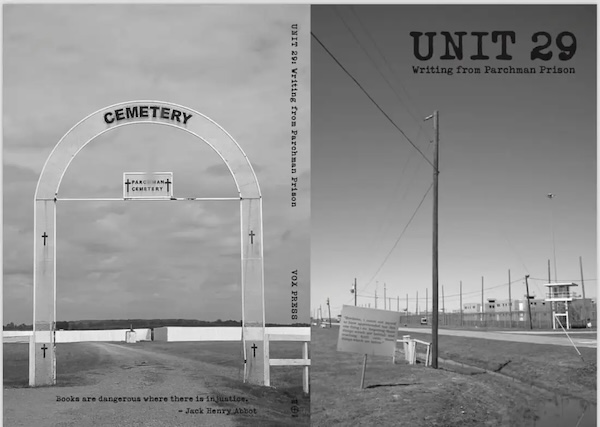

Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison, compiled by Louis Bourgeois. Vox Press, 215 pages, $19.99.

In an essay titled “My Secret To Passing Time,” Victor Wilder writes that “it’s hard to deal with time. The walls start to talk to you.”

In his composition titled “Thoughts Everyday,” Elijah Stamps ends most of the paragraphs with something like, “it’s time to lay back down and sleep,” because he has found that he can “speed time up by going to sleep.”

Wilder and Stamps are among the men whose writings have been collected in Unit 29. All the writers are serving sentences in Mississippi’s Parchman Prison.

This is no polished collection. The entries have probably been cleaned up in terms of spelling, but many of them are tired, repetitive, and bleak. Reading many of them in one sitting is not easy. This is not surprising. Incarceration is bound to be dreary and monotonous, even when it isn’t dangerous and terrifying, and incarceration in Mississippi is worse than being locked up in lots of other places. An argument for this collection might be that anything anyone writes from prison should be published, since whatever it is, it will inform readers regarding the grim circumstances about two million of our fellow citizens endure everyday, day after day.

Some of the writing coming from incarcerated men and women these days provides evidence that while they are locked up, the writers have spent time learning that the U.S locks up people at a greater rate than any other country and how this nation’s history, laws, culture, and hypocrisy, especially among politicians and public officials, have brought about that circumstance. This is not the case for the writing coming out of Parchman. The men incarcerated there are focused on their personal circumstances and the conditions in the prison, where they are often placed in isolation for no reason; where they do not have decent meals; where their cells are vermin-infested, hot in the summer, cold in the winter, and flooded when it rains; where the correctional officers deal in contraband, and where the incarcerated men have sometimes seen those guards stand back as one inmate beats up another, in part because the guards are more inclined to cooperate with gang members rather than protect their victims. As Victor Wilder puts it in a short piece titled “Shower Call Down Below,” “Not only do the inmates gotta worry about the officers giving the other inmates the keys to run in your cell and kill you. But the officers gotta worry about other officers lettin’ the inmates kill them. It’s crazy but it’s so very real. This is a true story.”

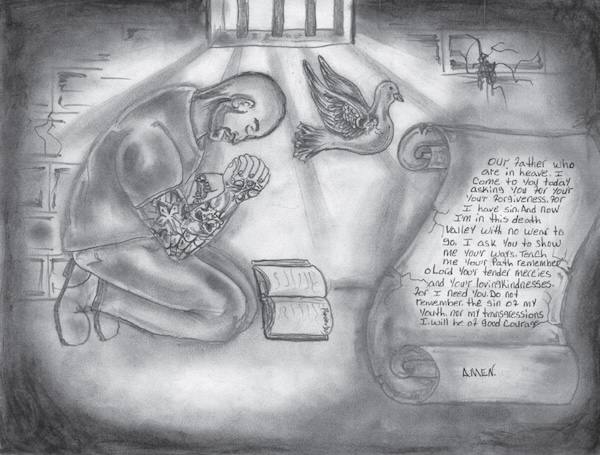

Anthony Wilson, incarcerated in Unit 29 at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, is the artist of the work entitled “Praying Convict of 29,” which is featured in Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison. Photo: courtesy of Louis Bourgeois

Many of the essays include testimonies. Several of the writers say they have found religion while they’ve been incarcerated. Others have found strategies to protect themselves from what they see around them. In an essay titled “The Way Things Are,” Jacob Neal writes about how “people yell a lot, argue, and behave aggressively” and asserts that “I’ve seen people throw feces, squirt urine, set fire, flood the building, and occasionally assault an officer over little things.” No wonder he concludes that “I try my best to be unapproachable.”

The value of books like Unit 29 is that they make the public aware of what the carceral system in this country is doing. Incarceration is meant to punish and rehabilitate the men and women who are locked up. But incarceration is also designed to undercut that mission: it separates those in jail and prison from whatever support systems on the outside might aid in their rehabilitation and from the world in general. Those isolated individuals often become angrier, more desperate, more depressed, and more damaged than they were when they were arrested and sentenced. Many of them should be in treatment for mental health problems rather than locked in 6×12 foot cells without windows or furniture. Attempted suicide is not uncommon. As Christopher Smith writes in an essay titled “Final Exit,” “At this point in my life, all I want is to not see the next day.”

Bill Littlefield volunteers with the Emerson Prison Initiative. His most recent novel is Mercy (Black Rose Writing)

Tagged: "Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison", Louis Bourgeois, Parchman Prison, VOX Press