Book Review: “My Affair with Art House Cinema” — Still Hot and Heavy

By Gerald Peary

It’s hard to imagine anyone connected with the movie world who is not appreciative of Phillip Lopate for the grace and intelligence and knowledge he has brought to film criticism.

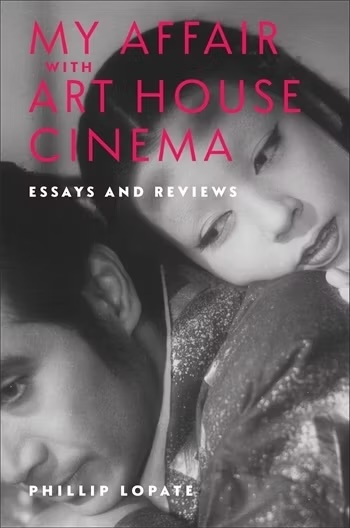

My Affair with Art House Cinema: Essays and Reviews by Phillip Lopate. Columbia University Press, 416 pages, $29.95 (paper).

Phillip Lopate has published volumes of poetry and fiction which, very sorry, I haven’t read. I’ve gravitated to where Lopate is most acclaimed, for being a nonpareil essayist, the author of such dazzling collections as Against Joie de Vivre (1989) and Portrait of My Body (1996). Luckily, he is also a true-blue cinephile and he has brought his illuminating talents to considerations of the cinema. Without ever holding a regular film critic’s post, Lopate has made a mark. He was on the selection committee of the New York Film Festival, and his astute reflections on cinema have appeared in varied places such as The New York Times, Film Comment, Cineaste, and in program notes for the Criterion Collection. It’s hard to imagine anyone connected with the movie world who is not appreciative of Lopate for the grace and intelligence and knowledge he has brought to film criticism.

Phillip Lopate has published volumes of poetry and fiction which, very sorry, I haven’t read. I’ve gravitated to where Lopate is most acclaimed, for being a nonpareil essayist, the author of such dazzling collections as Against Joie de Vivre (1989) and Portrait of My Body (1996). Luckily, he is also a true-blue cinephile and he has brought his illuminating talents to considerations of the cinema. Without ever holding a regular film critic’s post, Lopate has made a mark. He was on the selection committee of the New York Film Festival, and his astute reflections on cinema have appeared in varied places such as The New York Times, Film Comment, Cineaste, and in program notes for the Criterion Collection. It’s hard to imagine anyone connected with the movie world who is not appreciative of Lopate for the grace and intelligence and knowledge he has brought to film criticism.

Lopate and I are of the same generation — once film-crazy college students in the 1960s — and I believe we share a sensibility. We were enamored of the French New Wave and both taken in by film critic Andrew Sarris’s “auteurist” polemics in The Village Voice. Early on, we both fell on our knees before European art movies. I’m sure Lopate would nod with understanding about me at 16 going one week with three neighborhood friends to see L’Avventura and the next to see The Guns of Navarone, and me being the only one of the group who embraced L’Avventura and the only one bored by The Guns of Navarone.

It’s no surprise that in his new book, My Affair with Art House Cinema: Essays and Reviews, Lopate comes deliriously alive when it’s Antonioni on the big screen, likewise with other demanding international filmmakers, from Chantal Akerman to Marcel Ophuls. I have a similar impulse, always seeking out formally adventurous movies filled with moral complexity. We both opt for a properly framed long-held shot over fast cutting, mise-en-scène over montage. We both prefer a measured, unsentimental humanist cinema to facile and fashionable “edginess.” I endorse Lopate’s credo that the very best films will reveal some kind of “wisdom.” Clearly, entertainment and escapism are not ample reason for us to venture to the movies.

(That said, Lopate is more estranged from popular culture than I am. He declares, “[My] interests as various as they were, did not extend to rock music, comic books, best-selling novels.… I never saw any of the Star Wars movies or E.T.” Unlike Lopate, I grew up steeped in rock ’n’ roll and comic books, but I also put my nose in the air about bestseller fiction. Unlike Lopate, I’ve sat through a few Star Wars movies, though I only liked The Empire Strikes Back. And E.T. sent me to sleep.)

So how to approach this 400-page collection of film essays, which stretches through decades and covers so many directors and so damned many films? Lopate realizes that his book is unwieldy and perhaps intimidating. After arranging the essays alphabetically by the last names of filmmakers, he encourages readers “to hop around since there is no reason why this book needs to be read in strict order.” You could dutifully read the book straight through. Or adopt a more anarchic strategy. I immediately hopped around, as the author suggested. But more, I started skipping things, which he didn’t suggest. Lopate starts with “A,” Maren Ade. I’ve never seen the German filmmaker’s The Forest for the Trees, so why invest my time in reading the four pages describing it?

I leapt over 50 or so pages concerning films that have eluded me: Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses, Lino Brocka’s Insiang, Arnaud Desplechin’s A Christmas Tale, Emmanuel Finkiel’s Voyages, etc. I can save these essays for that proverbial rainy day.

But that left 350 pages to chew on, to sink into. I return to “A,” Belgium’s Chantal Akerman. The feminist-experimentalist, with whom Lopate feels an intense kinship, is someone we both care about. His is a sad essay written in 2015 soon after Akerman’s death at 65. “Chantal Akerman is gone. Hard to believe.” Lopate is critiquing here Akerman’s last film to be circulated, No Home Movie, a documentary essay about the filmmaker and her deep psychological attachment to her mother. The mother’s demise might have triggered the filmmaker’s suicide. Lopate openly loves No Home Movie, its shortcomings as well: “The film is slow, annoying — and real. It has more truth in it than 98 percent of art cinema or commercial movies.”

A scene from Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie. For Lopate, “the film is slow, annoying — and real.”

Lopate segues to a brief chronicle of Akerman’s whole career, both features and shorts. He applauds the difficulty of her cinema, her total disinterest in placating audiences. Says Lopate, “Some words that spring to mind about Akerman’s work are annoying, irritating, stubborn — but in the best possible sense. She was not obliging, thank God. She was not afraid to test your patience…. The paradox was that so much alienation and depression could coexist with such wonderment and glee at being able to stare at the world as it is. As it was. As it no longer is for Chantal.”

Sweet thoughts. Smart thoughts. As with so many essays in Lopate’s book, I know the filmmaker better after having read about her, and have a better entry to rewatching her films.

How about a picture that every cineaste knows so well, has seen so often? Is there still anything perceptive to say about Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless? Writing 40 years after its release in the USA, Lopate reported in 2000 on the Jean-Paul Belmondo-Jean Seberg classic in The New York Times. He vividly recalled his first seeing it: “It seemed a new kind of storytelling, with its saucy jump cuts, digressions, quotes, in-jokes, and addresses to the viewer. Yet underneath these brash interventions was a Mozartean melancholy.” “Saucy jump cuts”? “Mozartean melancholy”? I wish I’d said that! Lopate’s revisiting of Breathless in the new millennium — a display of early “woke”? — is also dead on: “What does date is the film’s lack of resistance to such sexist notions as the betraying female and its willingness to discuss women in terms of their body parts.”

Nice guy Phillip Lopate. Photo: Vermont Studio Center

Favorite chapters of mine in My Affair with Art House Cinema are appreciations of the works of filmmakers as diverse as Carl Dreyer (Denmark), Maurice Pialat (France), Hong Sang-Soo (South Korea), Abbas Kiarostami (Iran), Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne (Belgium), all of whom I champion also. More controversial, Lopate speaks up for John Ford’s 1953 Sun Shines Bright, which he confesses to love even while acknowledging its plantation racism. (I, on the other hand, can’t get by its retrograde racial politics.) Lopate also makes a valiant case for Richard Linklater’s Before Midnight, which I and many others have felt was a tepid ending to a trilogy that includes the masterly Before Sunrise and Before Sunset. Maybe I need a second look at a film Lopate praises so enthusiastically, asserting that Linklater is “the only one of his generation willing to address the disenchantments and readjustments of mature adults.”

A caveat: look elsewhere than this book for clever put-downs, or for angry attacks. Instead, My Affair with Art House Cinema is a book full of praise, full of thankfulness for movies that Lopate has an affection for, and which he finds worthy of elucidation. He writes approvingly about documentaries also, from those of Frederick Wiseman and Ross McElwee to Jean Rouch. And he writes lovingly about the filmmakers themselves (a wonderful essay on his friendship with Yugoslavia’s Dusan Makavejev) and ends with a series of tribute essays to fellow film critics. I’m glad Lopate says nice things about out-of-fashion Stanley Kauffmann and that he talks with ambivalence about Pauline Kael, but he definitely overpraises Manny Farber, who has been overpraised by practically every film critic. I also think he’s off-the-mark a bit when he describes Roger Ebert as “a thoroughly nice guy.” How about sometimes a very nice guy? Ebert also was a competitive control freak who loved to hear himself expound.

But what a minor quibble! My Affair with Art House Cinema is one terrific book. And by the way, Phillip Lopate is a very nice guy, or certainly seemed so the two times I’ve met him. And I thank him for one of the all-time best compliments, when he called me “a great rememberer” because my brain is so stuffed with movies.

Gerald Peary is a professor emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His last documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, played at film festivals around the world, and is available for free on YouTube. His latest book, Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, was published by the University Press of Kentucky. With Amy Geller, he is the co-creator and co-host of a seven-episode podcast, The Rabbis Go South, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Tagged: "My Affair with Art House Cinema: Essays and Reviews", Columbia University Press

Just to add to Gerald’s note about Lopate being a nice guy. I interviewed him when his 2008 book American Movie Critics: An Anthology from the Silents Until Now for Library of America came out. An excellent volume — and Lopate was an irrepressible, enthusiastic proselytizer for the value of film reviewing. When I mentioned I wished the volume had more examples of the film writing of Dwight Macdonald, he readily agreed. We were both admirers. If only Macdonald, who had so memorably deep-sixed movies like Ben-Hur, was around to take a swing at the pair of Gladiators.