Theater Review: A Dreamy and Acrobatic Hedda Gabler

Henrik Ibsen’s rejection of the everyday drives this compelling take on “Hedda Gabler” – the production generates a theatrical arena that is simultaneously acrobatic and surreal.

Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen. Translated by Rolf Fjelde. Directed by Ellie Heyman. Staged by the BU School of Theatre at the Boston University Theatre, Boston, MA, through May 13.

by Bill Marx

Alex Highsmith (Hedda) and Hampton Fluker (Lovborg) recall old times in HEDDA GABLER. Photo: BU Photography

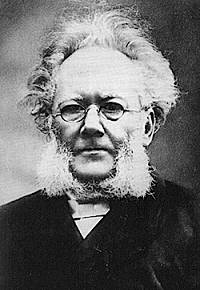

There are a number of reasons to see a play by Henrik Ibsen, especially when the dramatist is served up in an exciting if uneven experimental student production proffering a surreality that hops between the mesmerizing and the head-scratching. First off, it is a disgrace that the great Norwegian, the most important playwright writing after Shakespeare (Many would reasonably counter with Chekhov, but I disagree) doesn’t garner sufficient attention from local theaters — for example, the centenary of his death in 2006 was greeted by hundreds of productions and conferences around the world – in the Boston area a production of A Doll’s House was about it.

Part of reason for this neglect is that Ibsen productions tend to smother the dramatist’s still-invigorating modernism in a stuffy melodramatic realism (or suburbanize it, as Theresa Rebeck does in her Americanized update of A Doll’s House). In A Life in the Theatre, director Tyrone Guthrie sums up this stilted approach: “High thinking takes place in a world of dark-crimson serge tablecloths with chenille bobbles, black horsehair sofas, wall brackets and huge intellectual women in raincoats and rubbers.” The contrary sin is to attempt, as director Robert Wilson did in the disastrous 1991 production of When We Dead Awaken at the American Repertory Theater, to drag Ibsen kicking and screaming into postmodernism by slicing, dicing, and rewriting his scripts into a Dadaesque cul-de-sac.

The trick is to see that Ibsen remains with-it because, for all of their brilliance, his plays are sexy, witty, ironic, and mischievous. He nestles his visionary astringency in a frisky package, no more so than in Hedda Gabler, its anti-heroine one of drama’s most fascinating imps of the perverse. Her rejection of ‘normal’ life remains tantalizingly absolute, enigmatic, and thrillingly self-destructive.

In fact, critic Toril Moi argues that the play marks the first time in Ibsen where the “everyday is no longer represented as the only sphere where we have a chance to find acknowledgment and love; here the everyday is no longer potentially redemptive; it has become, rather, a petty and banal sphere of routinized, conventional, and empty transactions. In Ibsen’s previous plays, marriage stands as a figure for the redemptive everyday: in Hedda Gabler marriage and the everyday are equally empty.” Demonic individuality, fueled by an unrequited idealism, swallows itself up – life as a bad dream.

It is the rejection of the everyday that drives BU College of Fine Arts director Ellie Heyman’s compelling take on the script – she creates a dreamlike arena in which the sofas and tablecloths have been jettisoned, the central portrait of General Gabler and his Oedipal glare absent. The stage contains no furniture — dead flowers dangle from the ceiling, chandeliers hang at an askew angle on one side of the performance space, a huge staircase, a sort of existential lookout tower, sits on the other. There are no rooms or conventional boundaries, so Ibsen’s characters come on and off the stage every which way – jumping into the aisles, climbing into the audience box, wandering from backstage, entering from the top of the staircase, popping up out of the ground.

Alex Highsmith (Hedda) and Lily Narbonne (Mrs. Elvsted) play their version of musical chairs. Photo: BU Photography

In other words, this is an Ibsen gone simultaneously dreamy and acrobatic. In one memorable scene Hedda and Mrs. Elvsted chat about their beloved Eilert Løvborg while sliding, precariously, across the tops of three pianos, the instruments pushed around the stage by robed figures in black masks. Hedda and Mrs. Elvsted also race up and down the staircase, breathlessly trying to outmaneuver each other physically as well as psychologically. Pages of Løvborg’s manuscript detailing “the future” fall from the ceiling, to be swept away as if they were confetti by silent figures wielding brooms.

Heyman’s production of Jane Bowles’ In the Summer House last fall was a revelatory vision of a neglected American play, and here she uses some of the same interesting pictorial techniques, such as the division of the stage into horizontal and vertical symbolic spaces (Hedda stands on the top stair, towering over the little people), stylized physical movements, impressionistic sets, and fragmented sound effects.

The result is often reminiscent of the early Peter Sellars — intriguing ideas that at times make for problematic theater. The use of high decibel bursts of classical music melodies to punctuate the action overwhelm the voices of the actors, and the masked figures are not well integrated into the production – sometimes they are undulating reflections of Hedda’s repressed psyche, sometimes they are just there to move the props around. Unforgivably, Heyman buries the wonderful final line of the play, while Hedda’s burning of Løvborg’s manuscript loses its primal power here — dropping the pages into oblivion isn’t the same as seeing Hedda watch the flames swallow them up. And the long look at Hedda in her lingerie after she ditches the text comes off as silly directorial finger-pointing

Still, Heyman offers a briskly erotic Ibsen, finding floundering desire in surprising places and images. Hampton Fluker’s Løvborg has been working out at the gym in the Norwegian boondocks –- the actor has impeccable abs, and there is quite a bit of sexual heavy breathing going on, especially when he enters without a shirt, inviting Hedda and Mrs. Elvsted to ooh and aah over their prize. Here is a nervy production that makes it clear that the women want to claim more than just Løvborg’s prophetic mind.

The performances are a mixed bag, with Fluker’s Løvborg refreshingly aggressive and appealing, matched by Lily Norbornne’s energetic Mrs. Elvsted — the character is usually played as Løvborg’s drab helpmate, but here she arrives as a real match for Hedda, which is effective.

Less winning is Sam Tilles’ George Tesman, who comes across as a callow musical comedy lead. Alas, Norbornne catches his chipper comic energy in the final scenes of the production — they jitter about like wind-up toys. Naomi Lindh’s Aunt Tesman is played as an innocent do-gooder — someday somebody is going to find the emotional muscle in a character who has the strength to give of herself to others. The show’s Judge Brack, played by Mathias Goldstein, doesn’t exude the nimble guile, the sufficiently cold mask of sincerity, to be the “cock of the walk” in such a manipulative society.

Finally, Alex Highsmith’s Hedda is wonderfully snarly, and she conveys the character’s sexual confusion with gusto — she gives terrific hauteur. But the actress doesn’t convey a sense of the size of Hedda’s discontent, what Heyman sees as the figure’s transcendent yearnings. Highsmith’s Hedda is frustrated with the dunderheads around her, finally driven to nihilism.

Still, to paraphrase Judge Brack, people just don’t do these kinds of things to Ibsen, but Heyman proves that you can, and that the rewards are ample, making it clear, as if there was any doubt, that Ibsen remains our contemporary.