Visual Arts Review: “Conjuring the Spirit World” — Can You Believe Your Eyes?

By Debra Cash

This simultaneously entertaining and provocative show contests the premise that people today are invariably more sophisticated than those who lived in spiritualism’s heyday.

Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic, and Mediums at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem MA, through February 2, 2025. Exhibition travels to The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art | March 15–July 13, 202

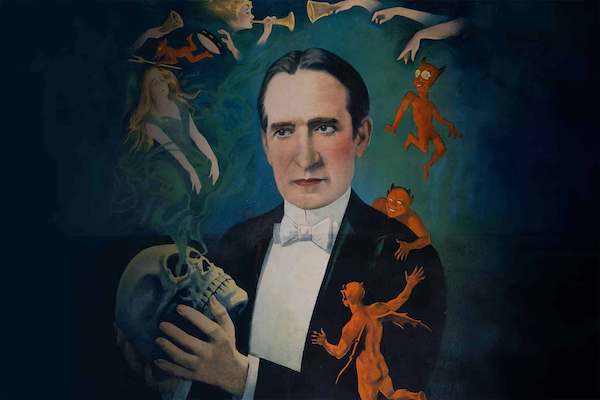

The Otis Lithograph Company, Cleveland, Thurston The Great Magician — The Wonder Show of the Earth — Do the Spirits Come Back?, (detail) 1929. Photo: Kathy Tarantola/PEM.

Mortality is unfathomable.

Matthew Brady’s photographs showing Civil War soldiers lying like so much spent materiel in a denuded Antietam encampment exposed the reality of dead men who would never find a resting place near their loved ones, north or south. Just brief decades earlier, photography had come onto the scene, in Susan Sontag’s phrase, as a nascent “technology of persistence.” Along with the telegraph – and who could have imagined nearly instantaneous communication across both time and space? –people were beginning to come to terms with the idea that limits could be breached, and maybe, just maybe, the finality of death could be vanquished.

That’s the thesis behind the Peabody Essex Museum’s simultaneously entertaining and provocative new exhibit Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic, and Mediums. With a range of late 19th and early 20th century posters, projections, props, ornaments and film snippets, a third of which belong to PEM’s permanent collection, the world of hucksters and true believers comes to life as a very understandable response to a world in which reality seemed hard to bear.

Artist in the United States, Ava Muntell – The Woman with a Million Eyes, early 20th century. Hand-painted photo collage. Collection of Tony Oursler. Photo: courtesy of Oursler Studio.

If this sounds like something we’ve been living through lately, that’s no accident. Curator George Schwartz is eager to make the connections explicit. While he’s not nearly as convincing as, say, the illusion of a floating handkerchief, this show contests the premise that people today are invariably more sophisticated than those who lived in spiritualism’s heyday.

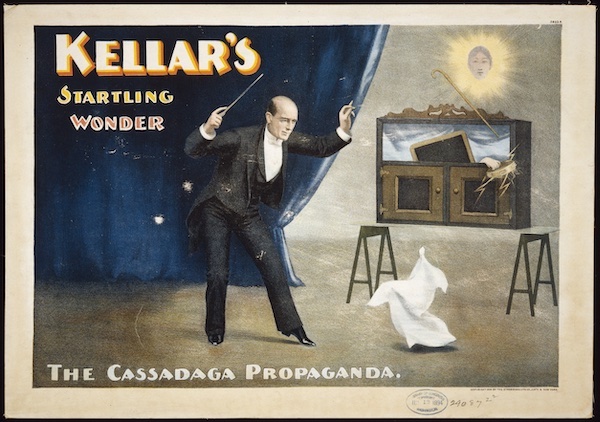

The damask-patterned show opens with posters – huge, brightly colored posters with magicians, mediums, and conjurers portrayed larger than life and often surrounded by red devils, ghouls, skeletons, and more than occasionally the skimpily dressed showgirl — announcing Magical Revues and Dark Seances. These vintage posters often posed the question “do the spirits return?” and the challenge might be taken up by a dueling poster saying “Houdini says no – and proves it!” The exhibit wall notes and the lavish Rizzoli catalog identify the names of some — but unfortunately not all –of the artists like Frederick Eugene “Kid” Jones — whose whimsy and design exuberance make these posters so memorable. Font fans will swoon: between the posters and handbills (some advertising events that took place in Salem) there are more creative layouts and more exclamation points (Manifestations! Tables Float in Midair!) than you can shake a magic wand at.

Conjuring the Spirit World arrays a compilation of props and stage apparatuses: spirit cabinets (watch the little video clip to see how the Davenport Brothers made bangs and clangs in a custom-built armoire despite being tied to chairs inside); Balsamo, the mechanical talking skull; magic slates; spirit trumpets that glow in the dark thanks to luminous (and probably toxic) paint; and projections like Pepper’s Ghost, demonstrated at PEM by an image of a WWI soldier in a doughboy helmet cautiously making his way across an open field, an effect deployed at Coachella to summon the ghost of Tupac Shakur.

Most of the objects on display are not aesthetic objects as much as persuasive ones, but it is worth spending the time to admire those collected or reproduced by LA-based prop designer John Gaughan, especially Emile Voisin’s brass “spirit bell” with its delicate brass parasol ready to capture the spirit emerging from a votive candle, and Gaughan’s gorgeous recreation of a High Victorian “spirit clock” with gilded Roman numbers.

Less effective are what should be the centerpiece of the PEM show: spirit photographs that proposed to capture the presence of ghosts. Some of this letdown is an artifact of familiarity: who among us hasn’t experienced double exposed pictures, not to mention Photoshop? But other aspects are the fault of the exhibition design itself: you have to squint into the display case to see a dark-suited William Lloyd Garrison encircled by the ghost of abolitionist Charles Sumner carrying spectral, broken chains.

The Strobridge Lithographing Company, Cincinnati and New York, Kellar’s Startling Wonder -The Cassadaga Propaganda, 1894. Lithograph. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Another lapse is the exhibition’s argument that spiritualism was progressive, anti-authoritarian, even feminist (a society in which women like sister mediums Kate and Maggie Fox were understood to be expressing personal agency). Nor is it evident that someone like Houdini who debunked magic tricks as just that, tricks, was using the scientific method unless you define every type of investigation of how something works scientific. PEM has an in-house neuroscience researcher, Tedi Asher, and the wall-notes and catalog essay attempting to pinpoint why people were so credulous are simultaneously too simple (in the dark you lose your depth perception) and too besides the point (the sociological explanations throughout the show are far more salient).

After a breathless tour of spiritualist moments from popular movies — Whoopi Goldberg in Ghost, Edward Norton in the period drama The Illusionist, Kenneth Branagh wearing a hilarious horizontal moustache as Hercule Poirot — the show ends with a tip of the hat to our own credulity and the emergence of deep fakes recently in the news including Taylor Swift’s now famous Harris-endorsing Instagram clap back complaining that “AI of ‘me’ falsely endorsing Donald Trump’s presidential run was posted to his site. It really conjured up my fears around AI, and the dangers of spreading misinformation.”

Taylor, conjure is the right word.

Debra Cash, a founding Contributing Writer for The Arts Fuse, is also a member of its Board.

Tagged: "Conjuring the Spirit World", Houdini, Magic, Mediums, Peabody Essex Museum, art