Visual Arts Commentary: Sunshine and Shadows — Sundials, Where Art and Technology First Met

By Mark Favermann

Considered the earliest integration of art and technology, sundials of various types have been around for 4000 years or so.

Vertical Sundial, 68 Monmouth Street, Brookline, MA. Photo: Mark Favermann

There is an elegant one at 68 Monmouth Street in Brookline, Massachusetts. Made in brass, this vertical sundial serves as a beautiful accessory to the façade of this mid-19th century house, built in 1853 for Amos A. Lawrence. The sight is rare: like four-leaf clovers, sundials are not that easy to spot today. Still, for the curious, there are a number of prominent and not so prominent ones scattered about Massachusetts.

Considered the earliest integration of art and technology, sundials of various types have been around for 4000 years or so. Put simply, sundials are the earliest type of timekeeping device; they indicate the time of day by the position of the shadow of some object (usually referred to as a “gnomon”) exposed to the sun’s rays. As the day progresses, the sun moves across the sky which moves the position and length of the gnomon’s shadow: the passage of time is visualized. Sundials have been fabricated out of a variety of permanent materials, they have been set horizontally, vertically, and angled. The objects have often been enhanced by art.

Most likely, the first sundials were vertical shadow-casters — the gnomon was a stick, a pillar, or a column. By about 1000 BCE, increasingly sophisticated efforts were developed: these devices consisted of a straight base with a raised cross piece set at one end. The base was placed in an east-west direction, with the crosspiece at the east end in the morning and at the west end in the afternoon. The cross piece’s shadow marked the time.

Of course, the innovative Greeks modified the instrument. With their geometrical prowess, they constructed sundials of considerable complexity. The Greeks developed instruments with either vertical, horizontal, or inclined dials, pointing to the time in seasonal hours. Predictably, the Romans modified and revised the instruments of other cultures, including sundials. During the 1st century BCE, in his seminal work De architectura, the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius designed a variety of sundials, some of which were portable. To him, a successful structure must proffer three qualities: firmitatis, utilitatis, venustatis (stability, utility, and beauty). Sundials were expected to incorporate these traits.

Vertical Painted Sundial, Kirkland House at Harvard University, by unknown builder. Photo: Harvard University Archives

Not surprisingly, medieval Muslim scientists drew on trigonometry to create sundials that decreed the proper time for prayer during the day. These technological pioneers also invented sundials with the gnomon parallel to the polar axis of the earth. With the arrival of mechanical clocks in the early 14th century, sundials with equal hours gradually came into general use in Europe. Throughout its history, efforts to make sundials attractive artistic objects never ceased.

In Massachusetts, sundials have long established themselves as striking visual presences. Of course, like most public art, the results over time have been variable. A sadly lost sundial was once set on the façade of one of Boston’s most famous buildings. Located high on the east wall of the Old State House, it was a vertical declining sundial that was built in 1713. The 6×4 foot dial was placed just above the third story window. The piece was restored in 1957, but over the next 50 years the background became a faded blue and the hour lines were increasingly hard to see. In the upper left corner of the dial, just above the gnomon, sat a small yellow sun. Parts of this sundial were removed during the building’s restoration in the late 1990s. Shockingly, the pieces were carelessly lost. The sundial was replaced by a mechanical clock whose historical appropriateness is questionable. The sundial’s original creator was probably one of the early builders of the structure.

In Lenox, there’s an interactive analemmatic sundial on the grounds of the Tanglewood Music Center. Placed nearby is a plaque that provides instructions for use. Stand at the appropriate engraved rectangle and you are transformed into a human gnomon. An analemmatic sundial shows how the position and the angle of the sun changes with the time of day and the months of the year. The position of a person’s shadow changes with the movement of the sun; the length of your shadow is dictated by the season. The sundial was created in 1993 by the Cambridge-based landscape architects Carr, Lynch & Sandell. The firm also created a more conventional sundial as a campus focal point for the Simplex Corporation in Westminster, Massachusetts. CLS was founded by the eminent urban designer Kevin Lynch (1918-1984).

Analemmatic Sundial, Tanglewood Music Center, Lenox, MA (1993) by CLS Landscape Architects, Photo: BSO/Tanglewood

Sculptor Lu Stubbs (1925-2020) created a sundial (1978) for Boston Children’s Hospital. The sculpture is a small round sundial that contains a mother bird on one side of the base and a nest with three baby birds on the other side. The mother bird holds a worm in her beak. The “worm” is the angled gnomon. When it was initially placed, the sundial was positioned on a large stone boulder at the now demolished Prouty Garden. Unfortunately, the sundial was moved several years ago to a rooftop space atop Boston Children’s Hospital’s garage. Thoughtlessly, the sundial was not set on a boulder and it is missing the gnomon “worm.” Shame on the philistines at Children’s Hospital.

In 1987, Stubbs created a sundial for a park in Boston’s Charlestown neighborhood. It is a 10-foot diameter bronze and granite horizontal dial with a 5-foot bronze gnomon and Arabic hour numerals set on a 2-foot-high granite base. Bronze images of Colonial American craftspeople embellish the face of the sundial; each hour features a different scene. The sculptures are of a grandpa holding a baby while looking at the dial from the east side and a child peeking from behind the 5 foot tall bronze gnomon

Birds with Worm Horizontal Sundial, Boston Children’s Hospital (1978), by Lu Stubbs, Photo by Dick Koolish

At Massachusetts General Hospital, a less visually successful sundial was created in 2004 by Nancy Schön, famous for her “Make Way for Ducklings” sculpture at Boston’s Public Gardens. The piece is dedicated to “Nurses” and “the Art of Nursing.” Located outside the Wang Ambulatory Care Center, it is a sculpture that features three women standing in front of each other with arms outstretched, each holding an object and reaching into the sky. The trio of nurses symbolize the past, present ,and future. Awkwardly, the three nurse figures are lined up to form a gnomon. The sundial’s scale, and the flatness of the figures, renders the piece graceless.

The styles of sundials across the state range from the figurative to the abstract, the traditional to the innovative. Located in fields at the University of Massachusetts, sits a work by Judith King, a rough-hewn “Sunwheel” (2000), a 130-ft diameter circle composed of 14 large boulders, 12 minor stones, and 4 flat center stones. A contemporary interpretation of a Native American sun-wheel, two major stones represent north and south: other stones mark east and west; and still others mark sunrise and sunset at the solstices. At Harvard University’s Kirkland House, there are two painted sundials above doorways. I wonder if Mark Zuckerberg ever noticed them when he lived there in 2004-2005?

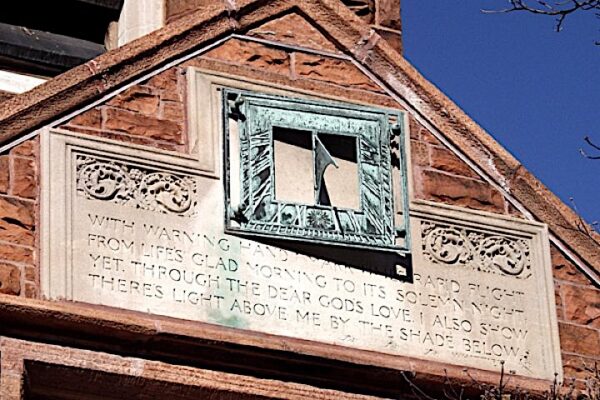

Vertical Metal Sundial, Story Chapel, Mount Auburn Cemetery (1896-98), Cambridge/Watertown. Photo: Jonathan A. Smith.

At Phillips Exeter Academy in Andover there’s a very large and ornate armillary sphere, 8 feet in diameter. The sundial was sculpted in 1928 by Paul Manship (who created Prometheus (1934) at Rockefeller Center in Manhattan). The armillary contains large figures inside the sphere at its base; equatorial circle features signs of the zodiac in raised metalwork. The dial sits on a light granite pillar that is 3-foot high and 4-foot diameter. Cambridge/Watertown’s Mount Auburn Cemetery hosts a vertical sundial, a 2×2’ bronze square plate that has Roman numerals at its center. The gnomon extends through the open space. The 1896-98 dial is mounted above a window of the chapel that faces south. A sundial signifying life and death?

Many traditional sundials proffered mottos. One of the best is “Tempus fugit velut umbra [“Time flees like a shadow”].

Mark Favermann is an urban designer specializing in strategic placemaking, civic branding, streetscapes, and retail settings. An award-winning public artist and sculptor, he creates functional public art as civic design and smaller functional objects. Early in his career, he was recognized for creating artistic events by transforming and documenting monumental structures into temporary sundials including Charlestown’s Bunker Hill Monument, the St Louis Arch and the then world’s tallest building—Chicago’s Sears (now Willis) Tower. The designer of the iconic Coolidge Corner Theatre Marquee, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and since 2002 has been a design consultant to the Boston Red Sox.