Book Review: “America and Other Myths” — Sucking “a Sad Poem Right out of America onto Film.”

By Trevor Fairbrother

In her fine book, Lisa Volpe examines mid-’50s picture-making expeditions taken across the US by photographers Robert Frank and Todd Webb.

America and Other Myths: Photographs by Robert Frank and Todd Webb, 1955. by Lisa Volpe. Yale University Press, 184 pages, $50.

Exhibition Schedule: Brandywine Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania (February 8–May 4, 2025)

In 1955 the Guggenheim Foundation funded grant applications from two photographers. The recipients were based in New York and, by happenstance, each had proposed a picture-making expedition across the US. Both were married white men who supported themselves with commercial work, but they differed in age, background, and temperament.

In 1955 the Guggenheim Foundation funded grant applications from two photographers. The recipients were based in New York and, by happenstance, each had proposed a picture-making expedition across the US. Both were married white men who supported themselves with commercial work, but they differed in age, background, and temperament.

Todd Webb, born in Detroit in 1905, was descended from English Quakers who emigrated to the American Colonies. Prior to the Crash of ’29 he worked as a stockbroker. In 1940 he committed himself to photography. Ansel Adams and Alfred Stieglitz, leading champions of the American sharp-focus “purist” aesthetic, gave him early guidance. Robert Frank, born in Zürich in 1924, began learning photography through apprenticeships at the age of 17. His family was Jewish. He emigrated to the US in 1947 and quickly landed a job at Harper’s Bazaar photographing fashion accessories for art director Alexey Brodovitch.

Webb’s application outlined a plan to follow “the routes traveled by the pioneers to the West,” journeying on foot and by boat. He would depict “vanishing Americana and the way of life that is taking its place.” Frank’s stated goal was “a broad, voluminous picture record of things American, past and present.” Each man wanted to publish a book combining his black-and-white photographs with text. In the short term, Webb allowed commissioned work to sidetrack him. Frank, however, forged The Americans, released by Grove Press in January 1960; in his introduction, Jack Kerouac said that Frank and his camera “sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film.”

Lisa Volpe, curator of photography at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, examines their projects in her fine book America and Other Myths. It is a revelatory experience because Webb’s 1955 photographs have received virtually no attention in recent decades. Her endeavor began serendipitously in 2019 when researching Georgia O’Keeffe, a longtime friend and recurrent personage in Webb’s photographs. She visited the Todd Webb Archive, a private organization in Portland, Maine, where the executive director, Betsy Evans Hunt, divulged the recent acquisition of a stockpile of materials Webb disposed of in the late ’70s. Webb’s negatives from the westward trek were in that trove, which spawned an exhibition combining the MFA’s collection of Robert Frank photographs with 2023 inkjet prints generated by the Todd Webb Archive. The accompanying book states at the outset, “the photographs from Webb’s epic journey were never published or exhibited, and eventually were lost.”

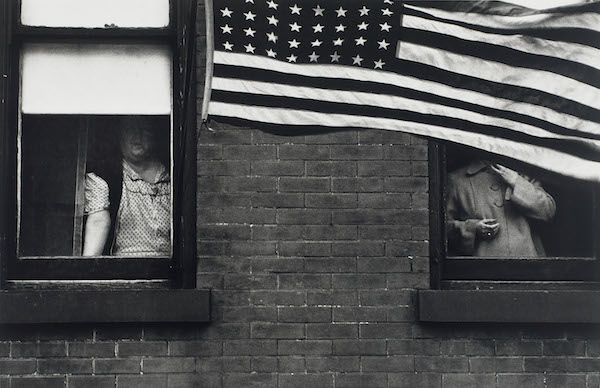

Robert Frank, Parade, Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955–56. Photo: courtesy of Yale University Press

“Home Truths,” the principal text in America and Other Myths, makes deft comparisons of the two projects. Frank traveled only by road, driving his used Ford coupe, while Webb walked and sailed by skiff to mimic early pioneers heading west. (After a few months Webb opted for a bicycle and then a motor scooter.) Frank experienced run-ins with police officers and was arrested twice: for driving around Detroit with a Black woman, and for looking and sounding foreign in McGehee, Arkansas. In 1956 the Guggenheim Foundation awarded a one-year renewal to Frank and a six-month extension to Webb. Volpe explores how each man felt disheartened by his experiences. Both witnessed racism toward Black and Native citizens. America’s hierarchical society is evident in their pictures, which detail the obsession with consumption and the promises of freedom and mobility that many workers knew to be illusory.

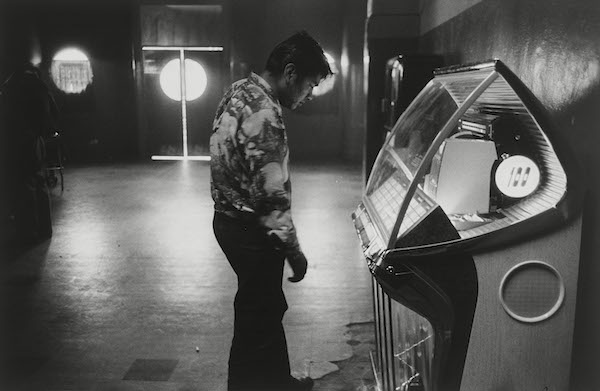

The book’s second section showcases the art: 102 single-page plates are divided equally between Webb and Frank. Many spreads present one image by each man; sometimes they show works by the same maker; sometimes a single image faces a blank page. Both men pictured crowded streetscapes, social confabs, factories, grave sites, cars, public transportation, neon signs, and national flags. It’s a treat to peruse these pages and test the images against the pigeonholing that decades of critical writing about each artist inevitably generated: Frank’s work is expected to be grainy, atmospheric, and unpredictable, and Webb’s more detailed, measured, and warmly on-topic. Consider two indoor images of lonesome western types. Frank snapped a man staring into a jukebox in a bar in Nevada; he seems to be alone but there are shadowy figures at the far left. Webb pictured a cowboy-hatted guy seated alone in a diner in Colorado, lighting a smoke; his craggy head, silhouetted by a window, is at odds with homey curtains patterned with trees. Each work showed sympathy for an underdog or lost soul, and each used compositional chiaroscuro to suggest melancholy within everyday reality.

Todd Webb, Diner, Ouray, Colorado, 1955. Photo: courtesy of Yale University Press

I like Volpe’s call to look at the threads of compassion in Frank’s mid-century work, to see that his “gruff realism” coexists with a kind of optimism. On the other hand, I’m leery of her allusions to Webb as a marginalized figure. (It may just be cooperation with the Todd Webb Archive’s grievance about the artist’s “ill-fated turn with an unscrupulous dealer” in 1976 and the loss of “a large portion of his archive.”) Volpe states that his work “was largely absent from the conversation” generated in the late ’70s, when academics and curators “reified” the history of American photography. That moment propelled Frank to stardom and enshrined The Americans as a momentous contribution to post-WWII art — a perplexing sequence of 83 images, an unromantic yet poetic dose of countercultural hard truths. While Webb’s art triggered no comparable impetus, he was a player. In 1977, writing for the New York Times, Gene Thornton called him “one of the last of the American regionalist photographers of the 1930’s to 1950’s whose number also includes Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans, Ansel Adams, the Paul Strand of Time in New England, and Edward Weston.”

Robert Frank, Bar, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1955–56. Photo: courtesy of Yale University Press

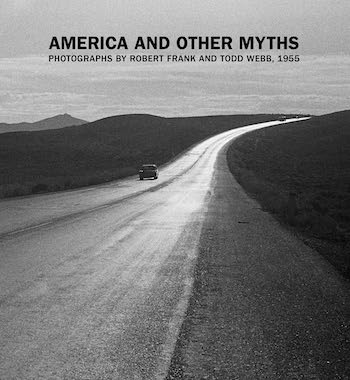

According to Volpe, Webb’s profile could not be “reestablished” until “the rediscovery of his archive in 2016.” This may explain why America and Other Myths ignores some important historiographical materials, including Webb’s 1991 Looking Back: Memoirs and Photographs, a monograph with some images from the 1955 project. Similarly, there is no mention of the stellar support of Keith Davis, the curator who in 1986 published a study of Webb’s photographs of New York and Paris and quoted a manuscript Webb drafted in the late ’50s for a book about Anglo-American westward expansion. Webb published two books in the aftermath of his Guggenheim project — Gold Strikes and Ghost Towns (1961) and The Gold Rush Trail and the Road to Oregon (1963) — and both are available in the HathiTrust Digital Library. The second one illustrates two photos that, according to the new book, were unpublished: the herd of buffalo in Kansas and the Nevada highway (featured on Volpe’s cover). My foraging also confirmed that the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona established an ongoing collection called the Todd Webb Papers in 1976.

The fact is, Webb quickly established an enviable stature in photography circles. In 1949 he earned a mention (and an illustration) in Beaumont Newhall’s The History of Photography, a landmark book that passed over the fledgling Frank. In 1956 the Art Institute of Chicago gave him a solo exhibition, after which he gifted prints of recent western photographs to the collection: one showed the Golden Gulch Saloon, Silverton, Colorado, another the nose and cowcatcher of a historic locomotive. In 1965 the Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, produced the exhibition and catalogue Todd Webb Photographs: Early Western Trails and Some Ghost Towns. But Frank reached greater heights. For example, the National Gallery rolled out its red carpet for him in the ’90s. That museum now owns over 5,000 Frank items, from photographs, work prints, and contact sheets to rolls of film. Webb is represented by four photographs: they are excellent vintage prints, purchased from one collector in 2001, the year after Webb died in Maine.

Trevor Fairbrother is a curator and writer. In 2012 he wrote Making a Presence: F. Holland Day in Artistic Photography in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name at the Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA.

I so look forward to the essays in The Arts Fuse by Trevor Fairbrother. He’s not only a great writer but a true expert on the issues of art. Nobody else could have disputed the argument that Todd Webb was a forgotten artist in such a definitive way, citing books, catalogues, exhibits which demonstrate that Webb has a trail.

I second your comment–thank you Trevor Fairbrother for your historical correction about Webb. His 1991 delightful memoir is a treasure of photography world details and personnel before its collection/fetishization began in the 1970s. Webb is notably represented in many American photography collections. Early among them is the NY Public Library, whose Picture Collection curator, Romana Javitz, was friends with the Webbs and acquired a selection of his prints for the department in the 1940s-50s. Decades later, in 1989 Todd and Lucille dropped in, casually out of the blue, because of their long friendship with Berenice Abbott, whose retrospective I had just organized there. They were charming and warm–I’m sure they wondered about the collection Todd sold to the Picture Collection decades earlier, which for complicated reasons, was not yet known to me (a story for another time).

Thank you, Gerald. The Washington Post’s coverage inspired my tangent into Webb’s history with its hyperbolic title – “Two photographers traveled America. One became a star. The other vanished.” Sebastian Smee wrote a rave review that worked the polarities. He explained his quasi-religious faith in Frank and the thrill of his first encounter with so many 1955 works by Webb. Citing the musical paradigm of Antonio Salieri and Mozart, he admitted that it was “not quite fair” to make the juxtaposition because Webb “can only suffer by the comparison.” There was also the other hook of this project, which Smee described thus: “But after selling off his archive to a dealer who kept his work out of circulation, Webb fell into obscurity.” Feedback to this exuberantly penned write-up overflowed on the WaPo site, and that tipped me off. Numerous people balked at the notion of rivalry and argued that artists can be enjoyed on their own terms; for example, Tilly Glutz wrote, “Goodbetterbest is the curse of academic thinking. Always looking for the pyramid of value, and overlooking anything ‘lesser.'” Then there were many who wanted to know more the supposed vanishing of Webb in the late 1970s; for example, CashD77 wrote, “The author just tosses in that factoid and never explained why the dealer deep sixed the photos! And how did the current person get ahold of them for the exhibition??”