Book Review: “Blue Light Hours” — Unimpeachable Noticing

By Kai Maristed

Bruna Dantas Lobato’s sensibility is unmistakably original: she explores her protagonist’s life and surroundings like a dowsing rod, poking into closets, corners, and cupboards.

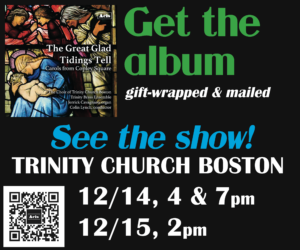

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato. Black Cat, $17.

The gifted young Brazilian translator Bruna Dantas Lobato (National Book Award for Translation, 2023) launched her own writing in English only a few years ago, to immediate success. Respected magazines Guernica, A Public Space, and the doyenne of them all — The New Yorker — have welcomed her onto their pages. This October marks Lobato’s much-buzzed debut as a novelist.

The gifted young Brazilian translator Bruna Dantas Lobato (National Book Award for Translation, 2023) launched her own writing in English only a few years ago, to immediate success. Respected magazines Guernica, A Public Space, and the doyenne of them all — The New Yorker — have welcomed her onto their pages. This October marks Lobato’s much-buzzed debut as a novelist.

Blue Light Hours is a short, (192 pp) atmospheric account of a long-distance mother-daughter relationship sustained by almost daily Skype calls, over the span of roughly one year. The daughter’s freshman year as a scholarship student at a private Vermont college, to be exact. The cold, well-to-do, bucolic north is a jarring, bewildering, exhilarating contrast to the small apartment she lived in all her life up to now with Mama, or Mãe, who remains, filled with both pride and misgivings, in their hometown of Natal, Brazil.

Let us all hail our literary translators. Don’t expect AI to fill in any time soon. It’s a wonder any human takes on this difficult, ill-paid vocation, one that requires skill and education and finesse and time. You do it for love, not fame. Until recently, translators weren’t always credited on book covers! Yet in our discordant and bellicose world, it is they who enable people to truly and viscerally comprehend each other’s worlds. The Words That Remain, the novel by Stenio Gardel that won Lobato a National

Book Award for translation, intertwines the burden of being gay in a macho society with poverty and illiteracy in Northeast Brazil. A far cultural cry from (the unputdownable, by the way) Call Me by Your Name.

Here’s an interesting thing I’ve noticed about translators, though. While they normally do a fine job of rendering a ‘foreign’ language in their native tongue, they are not always completely fluent (verbally, or in nuances of dialect) in the second language. No matter. They have friends, colleagues, and books they can consult to make the printed work as right as possible.

How exceptional then, is Bruna Dantas Lobato, who elected to translate from her native Portuguese — she grew up in Natal — to English? Granted, she prepared hard for the literary Olympics. Her listed degrees are a Bennington B.A., a fiction MFA from NYU, a literary translation MFA from Iowa. Roughly enough university years to earn a medical degree. Add to these multiple grants and stays at, e.g., Yaddo and McDowell. Add the fine-honing of many teaching appointments.

Similarly, few authors have ventured to write and publish original work in a second language. Milan Kundera (Czech to French) and Jhumpa Lahiri (English to Italian) come to mind. Both began their adventures in the present tense, for obvious reasons, and in plain declarative sentences for the most part. (We’ll leave multilingual geniuses like Conrad and Nabokov out of this, lest they ruin my argument.)

To repeat, Blue Light Hours, written in Lobato’s second language, is a short book. Framed in the past tense (brava), the prose proffers a silky surface, devoid of sharp outcroppings, that one associates with writers’ group critiques and multiple edits. Or, this may simply be Lobato’s natural style. Unmistakably original is her sensibility: she explores her protagonist’s life and surroundings like a dowsing rod, poking into closets, corners, cupboards. Her work vibrates when it touches the tender, or the amazing, that is hidden in plain sight in everyday things.

“I kept [my mother] up-to-date on who was fighting with whom… My neighbors were in the midst of thermostat wars, my professor told me I was the only one who came to office hours, Kayla was drinking too much and Safia had taken up smoking to boost her social life, though I didn’t think it was working.”

“It had snowed again… Out there, every surface was covered in a thick layer of white. There was ice in the trees, already dripping. We walked past couples with dogs in little boots, baristas smoking cigarettes outside the coffee shop, wind chimes swinging on porches.”

Brazilian author Bruna Dantas Lobato. Photo: Ashley Pieper

It’s the pleasure of these apercus that keeps one turning the pages, reading Blue Light Hours (twice, on my part) not so much for story as for the author’s unimpeachable noticing.

And the story? Not much to write home about. One senses that the novel owes much to Bruna’s Bennington journal. Chronicle of a girl’s first year away from her equatorial home and the safe, fusional relationship with her mother. Now come guilt, homesickness, snow, and differentness. The modest experiments with alcohol, one kiss. Not that storytelling, let alone thick plotting, would seem to be this writer’s goal.

Nonetheless, I was geared up for a denouement in the final pages, a surprise or twist. Instead, without giving much away, let’s call the ending an organic development. It’s heartening and also filled with saudade, which is untranslatable Portuguese for a sort of yearning nostalgia.

Much of the book consists of dialogue between mother and daughter via Skype (Zoom in an earlier incarnation). Their exchange sounds genuine enough, as they struggle to surmount this separation, but it tends to be repetitious. Hardly worth eavesdropping on, except for a scene in which the two get slowly and surely drunk together, toasting through respective laptop screens. A coming-of-age moment. Lobato’s achievement is to show how crucial internet technology is to these two women’s emotional survival and development. The cold Skype screen becomes the warm waters they can swim in, finding each other night or day. It allows not so much the rending of their lifelong bond, as it’s gradual transformation.

Soon in her freshman year, our unnamed protagonist’s major dilemma arrives: whether or not to return to Brazil. Ever? Even just once, if only to pay her ailing mother a visit? We’re told she can’t afford it (only $460 r.t. according to Expedia) although she has been given a ‘full ride’ and a twenty hour a week job in the mail room. (By the way, do colleges require or permit 20 hours of work-study a week? It’s a lot. Another odd detail: in October, she sees “little spotted fawns” with their dam in the forest. Not impossible, but a major statistical outlier.)

One comes to assume that this acclimatizing student would simply prefer not to go back to her old home. There is much tenderness and longing for the mother here, but scarcely a single recollection, warm or otherwise, of Brazil. It would be interesting to have that and, above all, to see her dig deeper into her avoidance, or fear: as if one visit back would threaten her hard-earned chance at the middle-class American life she’s fallen in love with. “I browsed through house listings for foreclosed properties… Oh how I wanted… a house that had been there before me and would remain long after, that was built on stable ground, no landslides, no floods, no rising ocean to swallow it.” Such desiring is not the end of their delicate mother-daughter relationship, but already a premonition of goodbye.

Kai Maristed (www.kaimaristed.com) studied politics and economics in Germany; she lives in Paris and Massachusetts. She has reviewed for the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, and other papers. Her four books include the collection Belong to Me, starred by Publishers Weekly, and Broken Ground, a Berlin Wall story. Recent work is in Five Points, Ploughshares, and Agni. Her new collection, The Age of Migration, winner of this year’s inaugural Kevin McIlvoy Book Prize, will be published in 2025.