Book Review: “A Shared Cinema” — A Dazzling Book of Interviews with French Film Critic Michel Ciment

By Gerald Peary

Thanks to publisher Paul Cronin for providing A Shared Cinema, allowing me and other film lovers hours of pleasure with the inimitable voice of the great French critic and editor Michel Ciment.

A Shared Cinema, a collection of interviews, edited by N.T. Binh, with French film critic Michel Ciment. Sticking Place Books, 352 pages, $35.

Perhaps you haven’t noticed, but the section in bookstores devoted to Film has dwindled and dwindled. It used to be rich with cinema history and celebrations of prominent movie directors. All gone. What’s being stocked now are “how to” careerist books on writing screenplays and getting into film production. Publishers also have cut down severely on what film books they will contract. There’s room still for a celebrity bio or the inside saga about the making of a famous Hollywood picture. But that’s mostly it. Why take a chance when nobody today, it seems, wants to read seriously about film?

Enter Paul Cronin, a British writer and critic living in the USA who is an impassioned lover of cinema. For good or ill, he has initiated a one-person small press, Sticking Place Books, to go against the grain, openly fight windmills. His high-minded mission in our uncaring era is to curate and publish educated, thinking-person’s film books. Among other projects, he has started a series that no one before has considered worthwhile: interview books with prominent film critics discussing their lives, their aesthetics, their cinephilia. What bravery, at a time when film criticism is so devalued and disrespected, when, thanks to the promiscuous internet, “everyone’s a critic.”

I am so pleased with the inaugural volume in the series. It’s Shared Cinema, translated into English from a dazzling 2014 book of interviews with the great French film critic Michel Ciment (1938-2023), conducted by his Gallic colleague N.T. Binh. Ciment is best known in the USA for his nonpareil interview books with filmmakers: Elia Kazan, Joseph Losey, John Boorman, and Jane Campion. His 1983 Kubrick, revelatory conversations with the maestro filmmaker, has been a consistent international best-seller, bypassing even the success of the first full-length book of interviews with a director, Hitchcock/Truffaut (1966).

In France, Ciment was a public intellectual, appearing for many years on Le Masque et la Plume, a popular radio program, also giving well-attended lectures, making documentaries, and putting his stamp on film culture by advising film festivals on what to show, including decisive years helping to program Cannes. But he is most important by far for his half century editing the extraordinarily influential film journal, Positif. Its Paris rival since the ’50s, Cahiers du Cinema, garnered all the publicity because of its polemical tone and because it was staffed by future all-star filmmakers including Truffaut, Godard, Rohmer, Chabrol, Rivette. But in Ciment’s view, Positif was “saved” because its knowledgeable contributors stayed on as film critics. And the magazine always adhered to Ciment’s non-ideological left-of-center philosophy: “Throughout human history…man is happiest under social democracy.”

Whereas Cahiers through the ’70s kept changing writers and drastically shifted its ideology from rightist libertarian to doctrinaire Maoist ultra-leftist to left-wing heavily theoretical, Positif held steady, Ciment says, being “anti-imperialist, anti-Stalinist, anti-fascist, totally in sync with the May ’68 movement.” Cahiers made its name by championing “auteurism,” especially with American and French cinema. Positif, while also “auteurist” but in a less strident way, cast a larger international net, discovering many Italian directors but also political filmmakers from Latin America: Argentina and Brazil. In fact one, Positif film critic — a woman, how rare!- — not only advocated for radical Latin American cinema but she died in Guatemala as a revolutionary. The world could use this now non-existent volume: The Collected Film Criticism of Michele Firk (1937-1968).

What other differences between the magazines? Cahiers in the ’50s proudly denounced filmmakers whom they found wanting, whose work was deemed too impersonal, too earnest and political, or, with elder statesmen French directors, too creaky and pretentious, the so-called “cinema of quality.” Positif under Ciment was far more generous in what filmmakers it approved. The magazine liked some those old French directors and, in opposition to Cahiers, it especially endorsed filmmakers who were openly political.

Positif could be curious about film theory but never an advocate of it. “What characterizes the writing is a rejection of jargon and inflexible theorizing,” says Ciment. And one more thing: Positif often had a surrealist bent, appreciating what Ciment calls “directors of the imagination.” Not just Bunuel but “Murnau, Boorman, Michael Powell, Kubrick, Fellini, Polanski, Tim Burton…”

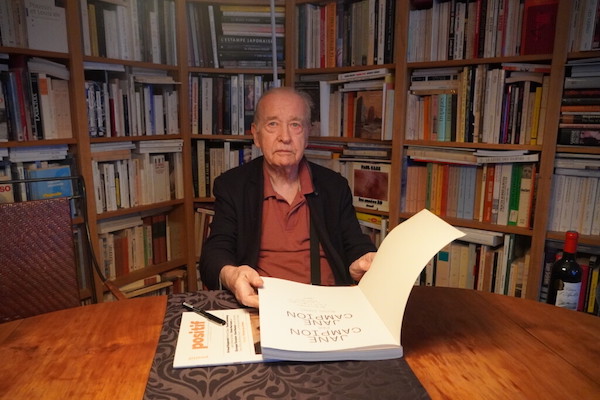

Film critic Michel Ciment.

A Shared Cinema has room for not only Ciment’s film opinions but his biography. A son of French Jews, his family somehow survived deportation by going into hiding in France. He lived most of his life in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, surrounded conveniently with movie houses. As a child, he loved popular movies starring Errol Flynn and Gary Cooper. Ciment: “I feel a little sorry for anyone who discovered cinema in a university class, watching things like Duras, Godard, and Straub.” At 18, he started going religiously to the Cinematheque Francaise. There, he first saw silent cinema. “I discovered the power and importance of the image.”

Propelled by his love of American movies, Ciment came to the US and drove and hitchhiked across the country. Afterward, he attended Amherst University and started the institution’s first film society. Back in France, he joined Positif in 1966. Quickly, he found his permanent home: “Positif…it’s never been exactly synchronous with the spirit of the times…. It doesn’t ride the waves of the zeitgeist….A person who reads a journal like Positif, with its page after page of lengthy articles, is a person who enjoys reading…Our readers appreciate the quality of writing….As you can see I’m a huge fan of Positif.”

And, from afar, so am I. When I was a graduate student in the ’70s, I don’t know why I was motivated to mail an interview with an American “B” filmmaker across the seas to Positif. Happily, it was accepted by way of a warm letter from Paris from Ciment himself. He took the time to lecture me that Americans should stop neglecting the career of fashion photographer-turned-filmmaker, Jerry Schatzberg, especially his Faye Dunaway vehicle, Puzzle of a Downfall Child (1970). Ciment also encouraged more submissions. In all, three pieces by me were translated into French and appeared in Positif’s hallowed pages.

What excitement for yours truly, then just a fledgling film critic. What a boost to my ego, and to my confidence. Merci to Michel Ciment for starting me on forty-five years of film writing. And thanks to publisher Paul Cronin for providing A Shared Cinema, allowing me hours of pleasure with Ciment’s inimitable critic’s voice.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world. His latest book, Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, has been published by the University Press of Kentucky.