Theater Review: A Warm-Hearted “Winter’s Tale”

By Bill Marx

A relaxed, humane kindness shines through this staging of Shakespeare’s hymn to reconciliation.

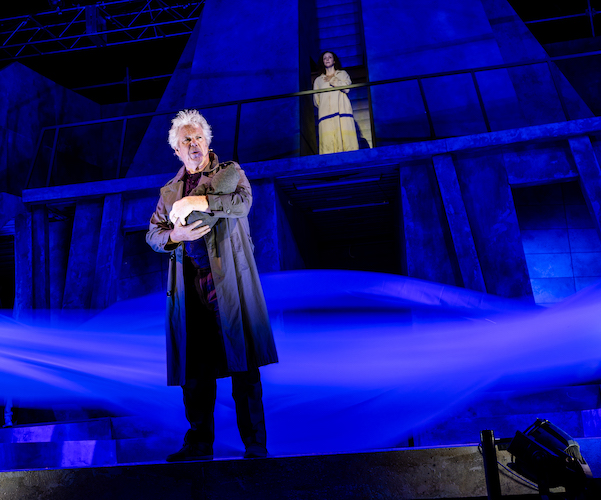

The Winter’s Tale by William Shakespeare. Directed by Bryn Boice. Staged by the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company at the Parkman Bandstand, Boston Common, through August 4.

Omar Robinson, Marianna Bassham, and Nael Nacer in the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company’s production of The Winter’s Tale. Photo: Nile Scott Studios.

In the Jacobean period, “a winter’s tale” was slang for something fanciful, unreal, a yarn told at the fireside. And, because it contains volatile extremes of hot and cold, The Winter’s Tale has been classified as one of the Bard’s problem plays. The icy bleakness of Leontes’s jealousy is jettisoned for warm, rural comedy-romance, which gives way to a vision of reconciliation and renewal at the play’s conclusion. The challenge for a staging is to cover — with equal depth — the script’s fire and ice, the inhumanity of its (woman-hating) tragedy replaced, at the behest of healing Time, by repentant love, culminating with a glimpse of the miraculous. The Commonwealth Shakespeare Company production steers a middle course through these zigs and zags; at its best, it is modestly warmhearted, moving, and amusing, though it slides at times into the superficial. On the one hand, that means the proceedings stint on the script’s arctic abyss and magical high. Still, a relaxed, humane kindness shines through this staging, particularly by way of the dignified agility of the performances of Marianna Bassham as Hermione and Paula Plum as Paulina.

Shakespeare does not make the bleakness of the first three acts easy to take. The King of Sicily, Leontes, comes off as a weird combination of Othello and Iago — a figure of motiveless jealousy. At the flip of a psychotic switch, he turns from loving friend and devoted husband into a monster convinced his pregnant wife, Hermione, has been having it on with his longtime buddy, Polixenes, the King of Bohemia. Some critics see Hermione’s efforts to convince Polixenes to extend his stay as triggering Leontes’s repressed misogyny. I don’t buy it — for mystifying reasons the monarch becomes imprisoned, instantly, in his own sick hallucination. The problem for Nael Nacer and director Bryn Boice is to register the twists and turns in Leontes’s delusive rants, to modulate the character’s psychological meltdown until he looks at his baby daughter, a scene where flickers of feeling are immediately shut down. Boice has Nacer’s Leontes stridently address the audience; it is as if he thinks he is going to win us over — fat chance of that — while the guys around the king stand looking bewildered and hapless, maybe wondering who in the hell he is raving at. (Tony Estrella is a solid Camillo, the one courtier in Leontes’s court who rebels against the insanity.) Add the stony, generally monochrome-ish set (patriarchal inhumanity) and you have a melodrama in which the villain has taken the helm and is steering toward the rocks.

Clara Hevia and Josh Olumide boogying with the cast of CSC’s The Winter’s Tale. Photo: Nile Scott Studios.

Thank Apollo for Marianna Bassham’s Hermione and Paula Plum’s Paulina. Bassham modulates deftly between charming hostess and grievously wronged innocent to a quietly fiery defendant in Leontes’s kangaroo court. Plum’s Paulina is commandingly feisty, yet naive enough to believe that the king will take pity on his baby daughter. The script jumps 16 years or so (Time helpfully clues us in) and the babe, now named Perdita and raised by a Shepherd in Bohemia, is being wooed by Polixenes’s son, Florizel. Boice has satiric fun with this act, turning what can be a somewhat tiresome sheep-shearing gathering into a campy dance party set to a techno-beat. The approach makes a hash of Shakespeare’s contrast between the decadence of the urban and the natural virtues of the pastoral, but after arid Sicily it is a relief. Clara Hevia’s Perdita and Josh Olumide’s Florizel make for an efficient romantic couple. Ryan Winkles’s energetic Autolycus is not only a fast-talking (and many accented) con man but a babe-magnet (a lampoon of Leontes’s claim we live on a “bawdy planet”?). He hawks his wares with panache to cooing shepherdesses before playing a crucial role in the plot. That said, the Jonsonian in me likes his grifters with more heartless edge. The gullible shepherds of Richard Snee and Cleveland Nicoll offer bracing farcical support.

In the final act, Perdita and Florizel flee to Sicily because the class-bound Polixenes refuses to let them marry, setting up a magical conclusion. Leontes, still in mourning for Hermione, vows to Paulina he will never marry again without her permission. Truths are revealed, the young’uns may marry, and Paulina brings all concerned to gaze at the lifelike qualities of a statue of Hermione that has recently been erected. Paulina asks the statue to descend — and it does. The production doesn’t generate much wonder (throughout, Maximo Grano do Oro’s lighting is somewhat flat). From what we see of Nacer’s Leontes, he doesn’t deserve this gift of amazing grace — nothing seems to have changed much for women in the kingdom, and he peremptorily assigns Paulina to marry Camillo. Hermione’s rejuvenation comes off as a happy ending (fantasy edition), a straightforward exercise in wish-fulfillment, underlined by the fact that characters have aged so little (may Plum’s Time be as graceful to us all).

Robert Walsh and the cast of the CSC’s production of The Winter’s Tale. Photo: Nile Scott Studios.

The staging doesn’t supply any particularly novel interpretations of the script (the cast members march the verse forward with clarity). There is the intriguing suggestion that the Bohemian bear that mauls Antigonus was inspired by (or embodies?) the spirit of Hermione, though if that were the feminist case why stop there? At the very least, Leontes should complain about nasty grizzlies in his nightmares. More puzzling is Boice’s hope, which she states in her program note, that “if we wreck our world royally, like Leontes …we can find strength, grace, and forgiveness from those we love and surround ourselves with, on the other side of penance.” Penance suggests that perpetrators will own up to the truth and admit their responsibility for catastrophe. (Fossil fuel company execs, for example, confessing that they covered up the fact that their product was wrecking the planet by warming it up ) In The Winter’s Tale, Apollo speaks embarrassing truth to delusional, self-destructive power — but that deity left the building a long time ago. Today, those in control rarely take the rap for doing harm. It is Leontes’s brand of irrational, unshakeable rage, and those who exploit it, that reflect a “world on fire in micro and macro ways.”

For me, the CSC production touched on the issue of the fragility of innocence. Like Desdemona, Paulina and Hermione believe that the guiltless are powerful, that innocence — when unfairly questioned — will be rewarded by empathy. To their horror, the women find that, in Shakespeare’s plays, innocence can never be strong enough. To survive, it must be defended by real world savvy (e.g, the wisdom of Othello‘s Emilia). Perhaps that’s why W.H. Auden believed that the scene in which the Shepherd rescues the abandoned baby is “one of the most extraordinary in Shakespeare…. it has archetypal symbols of death, rebirth, beasts of prey, luck.” For once, the Bard gifted an innocent with good fortune, gave purity a chance to survive in a dark world.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Bob Walsh, Bryn Boice, Commonwealth-Shakespeare-Company, Nael Nacer, Omar Robinson, Ryan Winkles, The-Winters-Tale

At some point might you not have congratulated the Shakespeare Commonwealth Theater for even doing this strange Shakespeare play before a mass audience and seemingly not dumbing it down?

The Winter’s Tale is a strange play — but not in the same problematic league as Merchant of Venice. According to Shakeseareances.com Winter’s Tale is 15th on the list in terms of live theater productions (tied with Richard III). It is produced more often than Merchant, Measure for Measure, all of the Henry plays, and Antony and Cleopatra. And I don’t think any production should be dumbed down for any audience — whatever its size.