Classical Music Album Reviews: “Brahms Reimagined Orchestrations” and Shani conducts Bruckner

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The Kansas City Symphony’s new Brahms album with outgoing music director Michael Stern showcases three of his works with keyboard in arrangements for orchestra; Lahav Shani’s cycle of Bruckner symphonies with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra continues with a sterling account of the Fifth.

Johannes Brahms revered composers of the past, especially J. S. Bach. So it’s fitting that the Kansas City Symphony’s new Brahms album with outgoing music director Michael Stern gives the composer a kind of “Bach treatment,” showcasing three of his works with keyboard in arrangements for orchestra.

Johannes Brahms revered composers of the past, especially J. S. Bach. So it’s fitting that the Kansas City Symphony’s new Brahms album with outgoing music director Michael Stern gives the composer a kind of “Bach treatment,” showcasing three of his works with keyboard in arrangements for orchestra.

Granted, with the exception of Arnold Schoenberg, whose recrafting of the G-minor Piano Quartet anchors the current disc, Bach had more creative and brilliant orchestrators rethinking his works than Virgil Thomson and Bright Sheng.

True, the latter’s Black Swan, a full-orchestra adaptation of the A-major Intermezzo (Op. 118, no. 2), is inoffensive enough. But the effort sounds blandly cinematic, despite a charming play of woodwind and brass colors during the Trio.

Similarly, Thomson’s setting of the 11 Chorale Preludes comes across as a dutiful orchestration exercise. True, it, too, has its moments. The strings-only setting of “O Welt, ich muss dich lassen” is touchingly inward. Meantime, the robust lines of “Herzlich tut mich erfreuen” bristle colorfully and there’s strong sense of musical space on offer in “O Gott, du frommer Gott.”

Yet “Mein Jesu, der du mich” is dry and “Herzliebster Jesu” chilly. The first “Herzlich tut mich verlangen’s” bass lines are almost defiantly thick, while “O Welt, ich muss dich lassen” come out with insistent brightness.

Of course, some of these issues may be performance-based: the latter’s stratospheric violin lines, for instance, sound anemic. But, given the vigor that marks the orchestra’s account of the Schoenberg, it’s not entirely clear that’s the case.

Rather, it seems that Schoenberg was the only one of this group of composers having any fun with his project. Accordingly, his arrangement of the Quartet, dense and over-the-top though some might think it, feels like a blast of fresh air.

The big moments are rightly dark and weighty. Though Stern’s account of the Andante is a shade spacious, it flows nobly; in this performance, too, the orchestra’s delivery of its Trio suggests that Schoenberg scored it after hearing Korngold’s score to The Adventures of Robin Hood. The finale, despite a couple of hesitant spots, zips right along.

Ultimately, then, it’s this Quartet that carries the album. Regardless, Reference Recordings’ engineering remains the gold standard, lucid, yet full and warm.

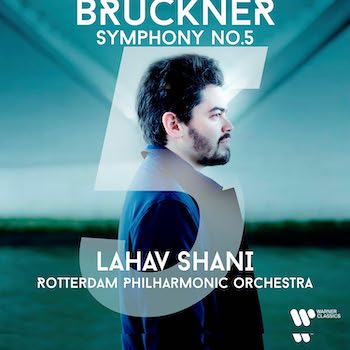

Anton Bruckner’s 200th birthday falls in October and, while his music often seems to be the domain of elder musical statesmen (think Herbert von Karajan, Bernard Haitink, Günther Wand, and Herbert Blomstedt), there’s no shortage of younger maestros trying their hands at it, too. One of the more successful of that demographic is Lahav Shani, who’s cycle of symphonies with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra continues with a sterling account of the Fifth.

Anton Bruckner’s 200th birthday falls in October and, while his music often seems to be the domain of elder musical statesmen (think Herbert von Karajan, Bernard Haitink, Günther Wand, and Herbert Blomstedt), there’s no shortage of younger maestros trying their hands at it, too. One of the more successful of that demographic is Lahav Shani, who’s cycle of symphonies with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra continues with a sterling account of the Fifth.

Though a big piece, the Fifth maybe represents Bruckner at his most approachable – and certainly his most contrapuntally confident. The composer’s mastery of polyphony is nowhere more impressive than in the Symphony’s finale, a massive double fugue that culminates in a chorale of shattering resplendence.

Arriving somewhere around the seventy-minute mark, the last often enough lands at the feet of an exhausted and depleted brass section. Not so in this recording: here, the Philharmonic delivers the Fifth’s apotheosis with gleaming magnificence. Though some might quibble that Shani doesn’t step back long enough to take in the view at this spot, there’s plenty of catharsis to be had, not to mention wonderfully balanced and impeccably articulated playing across the entire movement.

What comes before is, if not always so inspired, nevertheless agreeable. While the first movement wants for some mystery (and its sudden pauses lack a degree of intensity), Shani’s tempos flow well and the orchestra’s dotted rhythms are consistently crisp.

The great Adagio, on the other hand, is electrifying: rich, noble, spacious. Again, textures are lucid and, as in the finale, the proceedings are all thoughtfully paced. Much the same can be said for the Scherzo, whose short, folksy Trio makes for a peculiarly playful foil to the outer thirds’ obsessively driving rhythms.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: "Brahms Reimagined Orchestrations", Kansas City Symphony, Lahav Shani, Michael Stern, Reference Recordings