Book Review: “Corpses, Fools and Monsters” — The History and Future of Trans Lives in Cinema

By Steve Erickson

The book’s final words offer hope for the future: “Despite the compromised nature of the trans film image of the past, there are many new horizons possible for the trans film image of the future, and that canvas, with all these images, will tell our story in cinema.”

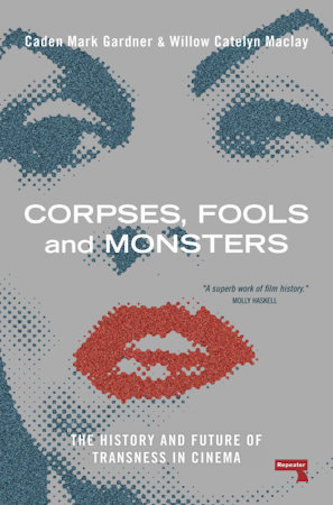

Corpses, Fools and Monsters: The History and Future of Transness in Cinema by Caden Mark Gardner and Willow Catelyn Maclay. Repeater Books, 332 pages, paperback, $19.95

Corpses, Fools and Monsters calls itself a book about “the trans film image,” rather than trans characters or filmmakers. It follows an elusive target, since trans people in cinema have been defined almost entirely from the outside until recently: Gardner and Maclay devote a chapter to cis actors’ performances as trans characters. They write “trans cinema is not yet a fully fledged sub-genre and has often been a scattering of images that are often recycled by non-trans filmmakers.” The book was born out of a frustrating exchange between Gardner and Maclay on 1999’s Boys Don’t Cry in the pair’s ”Body Talk” series. (This eight-part dialogue between the authors can be read here.) In Corpses, Fools and Monsters the two authors synthesize their voices. Maclay’s essays and reviews, presented on her Patreon page, lean heavily into autobiography, but the tone of Corpses, Fools and Monsters eschews the personal for the analytical. The writers’ stated model is Vito Russo’s popular gay film history The Celluloid Closet.

Corpses, Fools and Monsters calls itself a book about “the trans film image,” rather than trans characters or filmmakers. It follows an elusive target, since trans people in cinema have been defined almost entirely from the outside until recently: Gardner and Maclay devote a chapter to cis actors’ performances as trans characters. They write “trans cinema is not yet a fully fledged sub-genre and has often been a scattering of images that are often recycled by non-trans filmmakers.” The book was born out of a frustrating exchange between Gardner and Maclay on 1999’s Boys Don’t Cry in the pair’s ”Body Talk” series. (This eight-part dialogue between the authors can be read here.) In Corpses, Fools and Monsters the two authors synthesize their voices. Maclay’s essays and reviews, presented on her Patreon page, lean heavily into autobiography, but the tone of Corpses, Fools and Monsters eschews the personal for the analytical. The writers’ stated model is Vito Russo’s popular gay film history The Celluloid Closet.

The media’s most widely circulated images of trans people in the media have often been made by those who were hostile to them, hence the three negative archetypes cited in the title. Even when cis filmmakers have started out with good intentions, their work has reflected ignorance and unconscious prejudice or made itself easy to be co-opted by the genuinely hateful. (A few years ago, a trans woman’s harmless TikToks of herself dancing went viral; some viewers decided they showed evidence she was a serial killer, comparing her to The Silence of the Lambs’ villain Buffalo Bill and the famous “Goodbye Horses” scene.) Gardner and Maclay’s critique of Boys Don’t Cry repeats qualms that the film’s detractors have long held against it, but they go on to suggest that the real harm is that it is the only relatively popular movie to come along that has focused on trans masculinity. That means “the weight it has had to carry through the years was never sustainable.”

Corpses, Fools and Monsters traces the start of the trans film image to Christine Jorgensen, who became a celebrity in the early ‘50s (although the pair survey a few films made before her fame). She inspired Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda and Gore Vidal’s novel Myra Breckenridge. Without moving much beyond the topic of film, Corpses, Fools and Monsters manage to touch on larger cultural and historical contexts. For example, its chapter on ‘70s cinema also goes into the negative reception of trans writer Jan Morris’ memoir Conundrum; and the pair also quote from Nora Ephron’s appalling review of Janice Raymond’s book The Transsexual Empire, which popularized the topic of transphobic feminism.

Gardner and Maclay point to recurring narrative motifs, such as the reveal of a character’s trans identity as a twist. They argue that “it creates the assumption that a normative body is cisgender and anything outside of that realm is then subject for questioning, scrutiny, and disposability.” Their reading of 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs points to its flaws, but the pair respects the quality and complexity of director Jonathan Demme’s effort: “Demme’s film was not intended to be hateful, but the public transformed it into a vessel for wrongheaded ideas about transness… But Gumb {aka Buffalo Bill} was never meant to be seen as a joke. He was meant to be seen as someone who is in pain and inflicts that pain on others.” Similarly, they give 1992’s The Crying Game a fair assessment: “For everything good that The Crying Game does, it also stumbles, making for a complicated viewing experience of wins and losses.” The exploitative use of its reveal — Dil’s (Jaye Davidson) penis — as a marketing gimmick and then as a crude, insulting joke makes it hard to appreciate the value of the rest of the film.

Jaye Davidson and Stephen Rea in The Crying Game. Photo: Searchlight Pictures

Of course, Lana and Lily Wachowski, the most prominent trans filmmakers in history, are the subjects of a chapter. But the cis David Cronenberg receives nearly as much space, and that makes sense. The trans film image has continually passed through the horror movie genre and, in many respects, this presence has been extremely harmful. Psycho, inspired by serial killer Ed Gein, launched a strain of films associating gender nonconformity with murder. Dressed to Kill went much further, abandoning subtext by incorporating TV footage of Nancy Hunt, a real trans woman, and calling its villain, Robert Elliott, a transsexual. The mediocre slasher movie Sleepaway Camp would be long forgotten — if not for its surprise ending. Its protagonist, depicted as a teenage girl, has a penis. A trans-coded villain haunts this summer’s thriller hit Longlegs, even if those implications are much subtler than they used to be. Still, Maclay’s love for the horror film shines throughout her writing: she celebrates the liberating possibilities it can hold for radical re-imaginings of gender and sexuality. Drawing on sci-fi/body horror metaphors frees films, such as Shivers and Under the Skin, from having to meet the liberal requirements to supply examples of “good representation.”

Surveys like this tend to focus on stereotypes in mainstream movies and TV. (For an example, take the Netflix documentary Disclosure.) While this is important critical work, it can go hand in hand with how the media ignores independent films made far outside Hollywood. To its credit, Corpses, Fools and Mothers constructs an alternate canon that includes documentaries like Dressed in Blue, Southern Comfort, and The Salt Mines as well as the radical films of gay German director Rosa von Praunheim and Sadie Benning’s experimental Pixelvision video shorts.Gardner and Maclay’s pioneering examination comes at a good time: over the last few years, trans directors have made a splash that resembles the impact New Queer Cinema made in the early ‘90s, with films such as Jane Schoenbrun’s We’re All Going to the World’s Fair and I Saw the TV Glow, D. Smith’s Kokomo City, Alice Maio Mackay’s T Blockers, and Paul B. Preciado’s Orlando, A Political Biography. Yes, in some ways things are becoming more challenging for trans people, thanks to state repression and irresponsible behavior by the media and celebrities. But the final words of Corpses, Fools and Monsters offer hope for the future: “Despite the compromised nature of the trans film image of the past, there are many new horizons possible for the trans film image of the future, and that canvas, with all these images, will tell our story in cinema.”

Steve Erickson writes about film and music for Gay City News, Slant Magazine, the Nashville Scene, Trouser Press, and other outlets. He also produces electronic music under the tag callinamagician. His latest album, Bells and Whistles, was released in January 2024, and is available to stream here.

Tagged: "Corpses Fools and Monsters", Caden Mark Gardner, Trans Film Images