Book Review: “Goyhood” — A Rambunctious Romp and a Novel of Ideas

By Daniel Gewertz

Goyhood can be larger than life, and its plot is a real doozy, but this isn’t a lightly comic excursion: the religious and social consternations that roil the brothers Belkin are as earnest as they are outlandish.

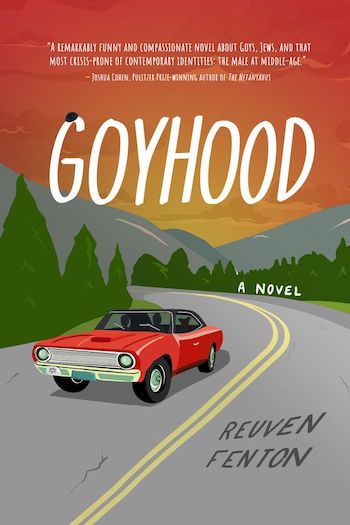

Goyhood by Reuven Fenton. Central Avenue Publishing, 275 pages, hardcover $28.

If book reviewing came with an instruction pamphlet, there’d be a warning against giving away too many of a novel’s complications. But Reuven Fenton’s wise and wonderful debut novel, Goyhood, makes that directive difficult. Even the title begs for explication.

The author is a veteran of New York City daily journalism. The first few chapters of Goyhood make it clear that Fenton’s style avoids both the blandness of mass-market fictioneers and the trendy precepts of MFA grads. Goyhood can be larger than life, and the plot is a real doozy, but this isn’t a lightly comic excursion: the religious and social consternations that roil the brothers Belkin are as earnest as they are outlandish. The prose flows with easy cadence and sly wit. And Fenton’s personable touch is an essential virtue here, considering the novel’s conspicuously singular storyline.

The prologue introduces the reader to the Belkin boys: 12 year-old fraternal twins, living in a dumpy house on the shabby side of a small Georgia town. Their father died before David and Marty were born, and their hard-drinking, loose-living mother, Ida Mae, is no role model. When an orthodox rabbi moves into town, he pays a visit to the Belkin household. Ida Mae takes this odd opportunity to inform her boys that — surprise, surprise — they’re Jewish! And on both sides, no less! Marty finds the day to be mystical. David does not.

We next see Marty after more than 20 years have passed. His identity as an ultra-Orthodox Jew dominates his every waking moment. He is living in Brooklyn, has changed his first name to Mayer, and has long been the son-in-law of HaRavYaakov Drezner, apparently the Grand Poobah of the exalted Ohr Lev yeshiva. Because of his marriage to Sarah, Mayer Belkin has agreed to remain in Brooklyn and to stay a Talmudic scholar his whole life. For unexplained reasons, he also promises his all-powerful father-in-law that he will renounce all worldly advancement: he must never train for the rabbinate or a faculty position. God knows why. Maybe Drezner wishes to ward off opportunistic sons-in-law. The couple — who’ve remained childless — live in a large Brooklyn house Drezner has gifted them. A lifetime of generous funds is tossed into the bargain. Mayer — the ultimate devotee — believes it is the magical deal of a lifetime; the reader may see it as more like a deal with the devil. This repressive brew of circumstances seems contrived and fantastical — a tailor-made plot-device. Still, the author certainly knows the world he evokes: before attending Columbia School of Journalism, Fenton graduated from New York’s Yeshiva University.

Mayer is quite content with his lot in life as a kept student, exempt from all adult responsibility. His wife is a citizen of the 21st century, but Mayer is content to be a stranger to just about every detail of temporal life. If another woman shook his hand he might start screaming in terror. To this fanatic a non-kosher cheese doodle would probably be tantamount to a satanic snack.

In the first chapter, Mayer Belkin’s secure little life is destroyed when he receives a phone-call from his estranged twin-brother. First, David tells him his mother has died. Then comes the scandalous detail: it was death by suicide, an especially monstrous sin to an ultra-Orthodox Jew. But that shock pales before the bombshell that arrives when he returns to his boyhood home in New Moab, Georgia. A reading of his mother’s rambling suicide note reveals that she has lied about her family background: she is not even 1% Jewish. In fact, her grandfather was a Nazi in Hitler’s SS. True, the boys’ long dead father was Jewish, but since Hebraic rules require a direct maternal line to be counted as a legit Jew, Mayer is suddenly not Jewish at all. Nearly a quarter-century removed from his Georgia boyhood Marty/Mayer is trapped in an ungodly “goyhood.” (A process called a giyur is needed to transform him back into a Jew.)

An eccentric opening plotline, yes, but the story deepens as it unfolds.

The lion’s share of the novel is a pell-mell, at times reckless road trip around the American south. David has chosen this adventure as a way to become closer to Mayer. They take the urn of mom’s ashes along, since she has requested in writing that they scatter her remains in a place that would make her laugh.

Goyhood maintains a good-humored, frisky touch, even while Mayer Belkin’s life is figuratively exploding . (In one scene in a fireworks store the explosion is literal.) But the novel is no picaresque comedy: that literary term indicates a free-roaming tale of peripatetic rogues, and while David might’ve formerly qualified as a rascal, the uptight Mayer does not.

David Belkin has led an unmoored life: his excesses and addictions included drugs, alcohol, gambling, and debauchery. But this former teenage delinquent is currently a millionaire, thanks to investing big in e-cigarettes. And, in his own way, he’s become a seeker of meaning.

The third-person narrative is closer to David’s voice than Mayer’s. Fenton often chooses slang words and fun phrases that mimic David’s earthy, mischievous nature. When a rabbi holds the urn containing the boys’ mother’s ashes, he looks like “he’d rather be carrying a human head.” Only rarely does a simile go haywire: after finding a long-lost, maltreated yarmulke, Mayer “mounted it on his knee and massaged the creases like a wildlife worker rubbing dish soap on a petroleum-soaked pelican.” (I can’t deny the simile made me smile.)

More than his metaphors, it is Fenton’s use of highly specific nouns that I found worth savoring: the exact type of tree, bird, weed, insect, flower, road, structure, building. One noun I had to look up was pergola, a type of trellised arbor. The book reflects the vocabulary of a writer who relishes the scope and diversity of the world. But he’s also a bit of a smarty-pants (to use a phrase his character David would like).

At 12, Marty Belkin was fascinated with birds and nature. As an adult, his only passion is Talmudic. Even though Mayer’s religious zeal felt divine and supernatural from the moment he discovered he was a Jew, it is clear that the fervor ended up shortchanging his adult life. Or is it only his involvement with his all-powerful father-in-law that is to blame? And this brings us to the critical line Fenton walks throughout Goyhood. A fair amount of Judaic pronouncements and philosophy are included in the narrative, and they set up a difficult question: Is religious ardor as harmful to Mayer’s life as addictions were to David’s? The author seems to suggest that slavishly following bundles of Orthodox do’s and don’ts hardly guarantee a life led with wisdom. And forget about the realm of physical joy! This skepticism is a brave choice for a Jewish novelist, particularly one still seriously practicing his faith. (In the author’s book jacket photo, a yarmulke is visible.)

Author. Reuven Fenton. Photo: courtesy of the author.

Despite David’s formerly wild life, he is not a shallow man. In the past he suffered through lows nearly suicidal in nature. His main desire throughout Goyhood is a noble one: to win back the love, companionship, and trust of his twin brother. Unfortunately, his adventurous bonding ideas are painfully incompatible for a brother who has relinquished nearly all worldly pleasure. Mayer is so different from the gutsy kid David knew as a boy he’s nearly unrecognizable. When the brothers come upon a maltreated, oil-covered dog left to die by the roadside, David attempts to feed and help the poor tied-up beast, while Mayer cowers in the car. “God,” David blurts out. “when did you get to be such a weakling?”

The dog, cleaned up, joins the journey. He has but one eye, so David names him Popeye. When the mutt is served some cooked sirloin steak in a restaurant, Fenton describes the moment: “His one working eye seemed to glow with perpetual wonder at all that was good on earth.” It’s not only a lovely line, it may be the kind of simple animal joy that David wishes for his brother.

Early on in the brothers’ road trip they visit New Orleans, and David runs into a platonic female friend, a fellow world-traveler named Charlayne. She’s an influencer, known to legions from her Instagram feed. She’s tall, beautiful, Black, stylish.. and Mayer is so fearful of her he’s nearly nonverbal. David regales the woman with colorful tales of his early life with his brother. Through this strategy Fenton cleverly gives the reader a picture of just how nervy, brilliant, and funny the former Marty Belkin was.

The novel’s other compassionate female character is a hip and brilliant Reform rabbi named Debbie Teitelbaum, who goes head to head on Talmudic interpretation with Mayer with a dexterity that approaches genius.

Goyhood is, by turns, a rambunctious romp and a novel of ideas. Yes, Fenton chooses to rev the action up to fever pitch for the climax, but most of the time he applies a subtle, even tricky touch. A stirring popular song is quoted several times along with mentions of the inspirational, wheelchair-bound pop idol who sings it. Because of the artful way the song is introduced, I had to Google the star’s name to be make sure he and his song were fictional inventions. Ultimately, this musical idol underlines one of Goyhood‘s central themes: powerful figures should be questioned, especially if they seem inspirational. To quote Bob Dylan, an often idolized Jewish-American pop star: “Don’t follow leaders/watch the parking meters.”

Daniel Gewertz has been influenced by the people he has interviewed for newspapers and radio, including jazz artists Ray Charles, Sonny Rollins, Artie Shaw, Dizzy Gillespie, Jay McShann, Gil Evans, Dave Brubeck, Keith Jarrett, Steve Swallow, J.J. Johnson and Milt Jackson; roots musicians B.B. King, Bill Monroe, Brownie McGhee, Vassar Clements, Phil Everly, Roger Miller, Carl Perkins and Bo Diddley; folkies Libba Cotton, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Leonard Cohen, Rambling Jack Elliot, Judy Collins, Roger McGuinn, Steve Goodman and John Prine; classic popsters Tony Bennett, Mel Torme, Eartha Kitt and Pearl Bailey; and film/theater artists Louis Malle, Edward Albee, Jeremy Irons, Glenn Close, Susan Anspach, Yul Brynner, Michael Douglas, Diahann Carroll, Jewel, Jack Klugman, and John Sayles. Daniel’s first live interview, at age 16, was with Art Garfunkel in 1966.

This mischling finds this premise fascinating. A want-to-read!

Thank you for the review. The book sounds interesting and fun