Book Review: Singer, Songwriter, and Guitarist Robyn Hitchcock — A Man Who Never Left the ’60s

By Scott McLennan

This unconventional memoir suggests that music can do more than just change ideas or beliefs — it can transform minds, overhaul brains.

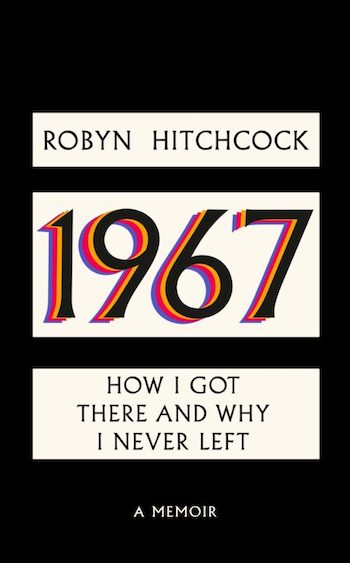

1967: How I Got There and Why I Never Left by Robyn Hitchcock. Akashic Books, 224 pages, $26.95.

Robyn Hitchcock occupies a particular slot in time — 1967, to be exact. That is the titular year his whimsical and illuminating new memoir is devoted (mostly) to, 12 months of adolescence that made an indelible impression on the now 71-year-old singer, songwriter, and guitarist.

Robyn Hitchcock occupies a particular slot in time — 1967, to be exact. That is the titular year his whimsical and illuminating new memoir is devoted (mostly) to, 12 months of adolescence that made an indelible impression on the now 71-year-old singer, songwriter, and guitarist.

Hitchcock’s music — and worldview — is steeped in classic psychedelia, the kind he stumbled upon when listening to the ways Syd Barrett–era Pink Floyd, along with the Incredible String Band, twisted and bent the conventional musical genres of pop and folk into unconventional forms, creating a fresh touchstone for musicians working in an era of heavy experimentation in rock ’n’ roll.

For Hitchcock, psychedelia was never about creating long tracks of exploratory, improvised music. Rather, he found a framework for his artistic tastes while staring at the cover of The Incredible Stringband’s The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion:

The cover alone of this new record … sums up everything I love about how 1967 is going so far. The saturated joy of it, the intricacy: everything seems to be turning into something else when you look at it closely; which for me is what defines psychedelia.

That transformative energy began pulsing through Hitchcock’s music from his earliest work in the late ’70s with The Softboys and then powered its way through a couple of dozen albums Hitchcock made with various other bands and as a solo artist, one who has been based in Nashville since 2015.

His book 1967: How I Got There and Why I Never Left employs a similar sensibility. As a narrator, Hitchcock leads the reader through a house of mirrors. At times Robyn plays the role of historian, piecing together his past, beginning in late-1966, when Bob Dylan’s music blew the mind of an awkward English teen when he was separating from his loving-but-pragmatic mother, distant and quirky father, two sisters, and the occasional live-in grandmother. That was the year Robyn was shipped to the Winchester College boarding-school to be primed for taking his place in society.

Then, sometimes, the contemporary Robyn comes along, speaking from the perspective of the present in order to add up-to-date commentary. A passage explains how, in the early ’60s, he and one of his sisters fell in love with The Beatles. The print turns italic and Hitchcock asserts, “Through the amber of sixty years, the Beatles glow ever brighter: they mean as much to me now as a white-haired pensioner as they did to ten-year-old 70 percent-grown me.”

Then Robyn the fabulist makes an appearance, placing figures from his life into wild and surreal situations. Classmates hang like bats from the ceiling or find themselves abducted by aliens. Pluto Trotter, a housemaster at Hitchcock’s school, his sister Belle, and their friend Alice are recurring characters in imaginative tales set around alcohol-fueled conversations. The Trotters and Alice are portrayed as tragic but sympathetic characters, symbols of a status quo that Hitchcock manically pivots to escape through the force of music.

What makes this memoir so gripping is that it is not only about Hitchcock the rebel, rejecting what is expected of him to embrace a career as a counterculture musician. It is also about how he wrestles with the contradiction of being a “teenager” embedded in 1967 for his entire life, knowing full well that the rest of the world will be moving further and further away from that year. There is high risk of becoming as sad and stuck as those who never leave the environs of Winchester College. A number of the current staffers were once students.

But Hitchcock bristled at Winchester’s rigidity, referring to its students as inmates. He pokes fun at the boarding school traditions, such as the coded language the students must learn as well as the hierarchies of privilege. At the same time, he recognizes the power of such rituals –in class bound England, conformity offers security.

Hitchcock and a few of his schoolmates devised alternative rituals of their own, based on shared musical obsessions. He creates vibrant, off-kilter portraits of students as they levitate while listening to Jimi Hendrix or fall under the sway of Brian Eno as he leads a free-for-all happening.

Robyn Hitchock in 2024. Photo: Emma Swift

Along with its many kaleidoscopic anecdotes, Hitchcock’s memoir confronts what it means to live life as a misfit. The musician isn’t interested in finding a seat at the table of proper British society. His escape into art and music is about liberation from the norm. But there is a price to be paid for such iconoclasm. Hitchcock’s struggle to come to terms with his rejection of society leads to destructive outbursts that erupt (apparently) for no reason at all. These explosions leave the writer perplexed — or at least unwilling to probe further.

The year 1967, of course, can’t last forever. The glory of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is followed by the critical disappointment with the film Magical Mystery Tour. Dylan reemerges late in the year with John Wesley Harding, which pulled back from the surrealist, electric sounds of his previous three records, albums that served as Hitchcock’s artistic North Star. He pays effusive homage: “‘Like a Rolling Stone’ hooked me, ‘Desolation Row’ pulls me in, and ‘Visions of Johanna’… more subtle, more engulfing: it becomes me.” There’s even a dream sequence in which Hitchcock presents a talk he had with Dylan. The “recreation” is sharp and convincing: the chat captures the cadence and contrarian nature of the Dylan you see in the footage of the interviews he gave in the ’60s, at a time when he was equal parts high-ranking celebrity and mysterious maverick.

The young Hitchcock has one burning question for the great songwriter: What is the meaning of life? The answer, of course, is played out in Hitchcock’s own decades-in-the-making catalog of songs, which were inspired by his revelations in 1967. This idiosyncratic memoir suggests that music can do more than just change ideas or beliefs — it can transform minds, overhaul brains.

Note: On August 5 at 7 p.m., Hitchcock will be reading from his memoir at Porter Square Books, 25 White St., Cambridge.

Scott McLennan covered music for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette from 1993 to 2008. He then contributed music reviews and features to the Boston Globe, Providence Journal, Portland Press Herald, and WGBH, as well as to the Arts Fuse. He also operated the NE Metal blog to provide in-depth coverage of the region’s heavy metal scene.

Fine review! Thanks from a fellow Arts Fuse writer & aging Fegmaniax & Wednesday Groover. Only seen him live a few times but have been involved in online groups about him since the 90s. Also been collecting recordings & transcripts of his monologues.