Film Reviews: Provincetown International Film Festival 2024 — The Significance of Meeting Face-to-Face

By Tim Jackson

Four films at this year’s Provincetown International Film Festival shared the theme of face-to-face communication, exploring the pleasures and pitfalls of encounters unmediated by screens and phones.

Independent cinema is about artists who produce works that fly under the commercial radar. At this year’s Provincetown International Film Festival there were a quartet of synchronous flights. Four films — The Good One, Didi, Daddio, and Daughters — shared the theme of face-to-face communication, exploring the pleasures and pitfalls of encounters unmediated by screens and phones.

Lily Collias in a scene from The Good One. Photo: Provincetown International Film Festival

In India Donaldson’s debut film, The Good One, 17-year-old Sam (Lily Collias) heads out on a three-day backpacking trip across the Catskills with her dad, Chris (James LeGros), and Matt, her father’s oldest friend (Danny McCarthy). Father and daughter have obviously embarked on hiking trips in the past. Matt, whose angry son has decided not to join them, is a less-than-savvy camper. He overpacks, bringing along a flask but forgetting his sleeping bag. Both men are divorced, and, outside of their work, their lives are far from settled. Throughout the hike and then at camping sites, Sam listens patiently to the men’s playful, though at times often quarrelsome, banter. She offers calm critiques and pithy observations about what she hears. In the wild she finds both the tranquility of the natural world and reminders of the discord of adult life. When Matt makes an unexpectedly inappropriate comment to Sam, she informs her father. His thoughtless response disheartens her and their trust is broken. She marches off to text with her girlfriend. Collias’s solid, understated performance in this coming-of-age yearn effectively dramatizes what it means to learn some hard lessons about disappointment and forgiveness.

Didi, Sean Wang’s semiautobiographical first feature, probes coming-of-age from another angle. The story is set in 2008, when many teenagers moved from MySpace to Facebook, and it examines how online identity became a critical socializing tool. Highly self-conscious about his Asian heritage, bowl haircut, and acne, Didi (Izaac Wang) would prefer to be called Chris. (Didi is a diminutive term meaning “little brother.”) Judd Apatow’s classic 2007 comedy Superbad pops up in one scene, an obvious clue to Wang’s intent: Didi is a nod to the teen genre about the resilience needed by geeky teens to find cooler identities. When Didi meets a group of older skateboarders, he brags to them that he is a videographer, though he has never actually shot one before. The videos he ends up creating are pretty shaky, but the kids don’t seem to mind. At home, Didi battles with his sister and mother (Joan Chen), but the family bond will triumph. When an older, half-Asian girl named Madi (Mahaela Park) unexpectedly comes on to him, Didi quickly finds her “likes” on MySpace and shapes the conversation accordingly. Typical adolescent awkwardness compromises this burgeoning romance. The kindness and honesty in these (and other) scenes avoid the bullying clichés embraced by many teen comedies. Maturing in the early days of social media required a new way of presenting the self — a point that this at times rambling comedy deftly illustrates.

Dakota Johnson in a scene from Daddio. Photo: Provincetown International Film Festival

The entire 90 minutes of Daddio, takes place in a taxi from the airport to midtown Manhattan. In a video that accompanied PIFF screening, first-time writer and director Christy Hall explained how she got her script to Dakota Johnson, who was enthusiastic enough about what she read to bring it to her Malibu neighbor, Sean Penn. The narrative comes off as a soapish spin on the Reality TV show Taxicab Confessions. An immediate contrast is set between Johnson’s character, Girlie, a 20-something professional programmer, and Sean Penn’s Clark, a foul-mouthed but discerning driver. “I like that you don’t sit back there on your cell phone,” says Penn to Johnson. Soon he is grilling her about her private life. Do cab drivers really do this?

As Clark praises her for talking openly person to person, Girlie hides lewd texts she is receiving from an older man with whom she is having an affair. During a prolonged delay because of a highway accident, their talk veers into uncomfortable personal revelations, including the fact that they both have had father issues. As time passes and Clark digs increasingly deeper, they each begin to question the value of their own relationships. The generational divide is bridged by their confessions of hidden pain. Yes, considerable suspension of disbelief is needed, particularly regarding the time it would take to travel by cab from airport to midtown. And this is a draggy and clichéd script; still, the skill of these two fine actors going head to head make this worth viewing.

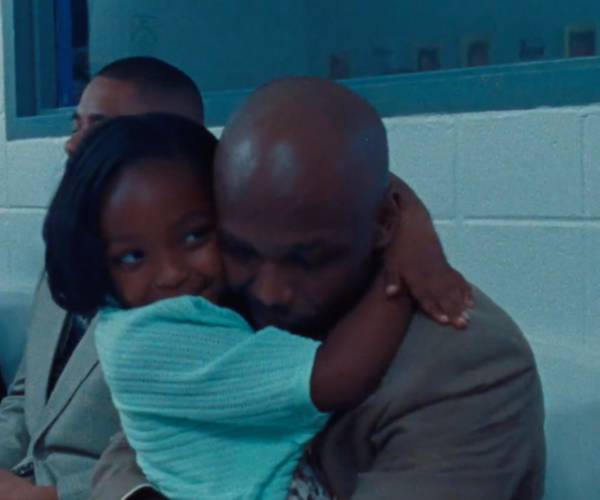

Face-to-face communication is the subject of the documentary Daughters, which follows four young girls (within a larger group) as they prepare to visit their incarcerated fathers at a “Daddy Daughter Dance.” The get-together was initiated by community activist Angela Patton, who co-directed the film with Natalie Rae. This debut feature received the Sundance US Documentary Audience Award and the Festival Favorite Award. Some of the men, who are Black and whose crimes are not revealed, have never seen or held their daughters. The film cuts between interviews of the girls voicing their expectations and the men in a 10-week group therapy program talking about responsible fatherhood. “I came from nothing, and I go back to nothing. I’m 25. I shouldn’t have nothing” says one man. The pending reunion deepens our compassion for all involved.

A scene from Daughters. Photo: Provincetown International Film Festival

Meanwhile, the girls don new dresses and style their hair. It is as if they are getting ready for a prom. Expectations vary widely. Anxious, the men are dressed in new suits as the girls wait in the prison hallway. Each group is scanned and then led to a decorated prison gymnasium. Tears flow as fathers embrace their daughters for the first time. The assumption is that some may never meet again; it may take years for others. Daughters leaves the impression that the “dance” experience has profoundly changed the fathers and daughters involved. Unsurprisingly, the program has been a success, with little recidivism.

The documentary notes that, in many prisons, visitation is now done remotely, using only a microphone and screen — no matter what the crime. This is the antithesis of rehabilitation. Patton’s TED talk on the program’s genesis can be found on YouTube.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter-skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story. And two short films: Joan Walsh Anglund: Life in Story and Poem and The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: "Daughters", "Didi", "The Good One", Christy Hall, Daddio, India Donaldson, Natalie Rae