Book Review: A Deep Dive into the Complex World of Ingmar Bergman

By Gerald Peary

Film historian Peter Cowie’s writing is always intelligent, if somewhat dry, and normally correct in its evaluations of Ingmar Bergman’s films.

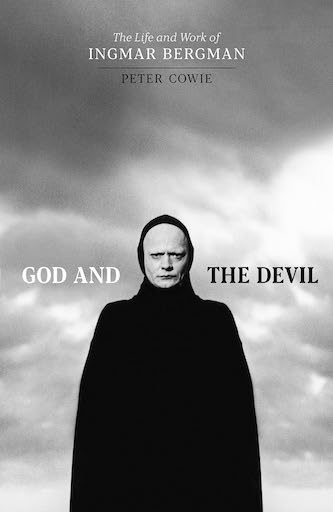

God and the Devil: The Life and Work of Ingmar Bergman by Peter Cowie. Faber & Faber, 416 pages.

Ingmar Bergman followed the well-traveled Picasso-to-Mailer path of high modern male artists: a life of prodigious artistic output combined with countless sexual partners, multiple wives. A final testimony to his ever-flowing virility, a gaggle of children, these, once born, totally neglected. In the case of the great Swede, he forged long and intense relationships with at least three of his finest actresses (Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, Liv Ullmann), married five non-actresses, and planted the seed for nine children along the way of directing several hundred ambitious theatrical productions and helming 48 feature films.

Perhaps unwisely, the Swedish biographer Peter Cowie chose to cover all of the above in his God and the Devil: The Life and Work of Ingmar Bergman, plus also the Bergman family story. Since we have no faces to go with the tales of Bergman’s parents, brother, and sister, nor are we familiar with his five wives, the complicated narratives about all — especially one spouse out, another one in — jumble together. We also know little about his first nine films before Summer Interlude (1951); having Cowie describe these apprentice works at length is educational, perhaps, but it also makes for boring reading.

But the biggest decision by Cowie that might be a stretch for non-Swedish audiences is his spending a great deal of the book describing Bergman’s work in the theater. Do we really need to know so many details of so many productions? Probably not. It’s wearying.

Still, it was fascinating to learn that Bergman directed on stage virtually every important playwright from Euripides to Shakespeare to Moliere to Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee, but stopping most often with the two most important Scandinavians, Ibsen and Strindberg. It’s fair to say that you can only really understand Bergman’s films if you realize how entwined they are with Strindberg, from the dream-state ambience to the estranged marital relationships. What is Persona without Strindberg’s one-act The Stronger? Many of Bergman’s productions, including some that came to America, were characterized by knowledgeable critics as the most powerful they’d ever attended in their lives. I confess to jealousy not to have seen any of them, and especially those featuring his beloved movie stars. Liv Ullmann as The Daughter in Six Characters in Search of an Author. Max von Sydow as Big Daddy in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and as the eponymous The Misanthrope. Young Bibi Andersson as Honey in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and, much older, as the pained mother in A Long Day’s Journey into Night.

God and the Devil is tipped a bit more to Bergman’s movies, and these are covered chronologically, with Cowie describing each production, often with a little backstage gossip, and then explicating the film itself. The writing is always intelligent, if somewhat dry, and Cowie’s evaluations of the films are normally correct. The book probably works best if the reader sees a Bergman film and then goes to the chapter about it, while the movie is fresh in one’s memory. Otherwise, it’s a slog reading through it all from beginning to end: too many plot summaries, perhaps too much about minor, unappealing Bergman films (Face to Face, The Serpent’s Egg, After the Rehearsal) of only academic interest. Fortunately, Cowie manages to be more exciting when he’s writing about the major films. His chapter on Wild Strawberries is particularly good, with many persuasive connections made to how very autobiographical this film is. There’s Bergman’s cheating mother, there’s Bergman’s cold, mean brother, there’s Bergman himself as the grouchy old professor who has spent his life avoiding commitment to other human beings.

Bergman the man? He’s a fascinating and deeply complex person and surely an artistic genius. Everyone worshipped him, and actors were honored to work with him. But it’s hard to make a case that he was a good guy. Once in a while, Cowie throws in a jammed paragraph listing a bunch of Bergman’s faults, which include temper tantrums, bullying people, thriving on power, being merciless when dropping his women companions, including wives, and, of course, caring not an iota about all those children. None of these criticisms were denied by Bergman himself. He puts them in his films, which feature children longing for parental love, promiscuous protagonists jumping uncaring from lover to lover, and, the biggest self-indictment, characters like Gunnar Bjornstrand’s father in Through a Glass Darkly and Liv Ullmann’s actress in Persona, who are pitiless and vampiric in their use of other people, sucking them dry for their own selfish purposes.

Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann in a scene from Persona.

Bergman also took the typical male high modernist route of finally finding true love with his final wife, who is domestic in nature and self-sacrificing in taking care of her man. That was a kindly, devoted woman named Ingrid Bergman (no relation), with whom he spent 24 blissful years. And who arranged a 65th birthday for Bergman in which his children from different relationships finally got acquainted! But there’s one major switch from the usual trajectory: Ingrid died before he did, of cancer, herself aged 65. Bergman spent his last years living by himself in his home on the island of Faro. And it’s this vulnerable, perhaps lonely old man who finally captured my heart in God and the Devil.

I was lucky to be among a handpicked group of international journalists who were invited to Faro a decade ago for Bergman Week, a yearly celebration of the late filmmaker. We toured his house, saw films in his private theater (Don’t dare sit on Bergman’s seat!), walked on the stony beach where Persona and other films were shot, and stood by the filmmaker’s austere grave. What a week! Anyway, I was primed to be moved by the final chapters of Cowie’s book, also the last chapters of Bergman’s life.

Of course, for this organized, ever-punctual man there was a daily routine. Breakfast at 7, then a walk on the beach. Writing at his desk after lunch, then a classic film projected in 35mm at 3 p.m. A nap, a light dinner, and then, his fun time, watching American network TV: The Muppets, Sex in the City. When Cowie once interviewed Bergman, he questioned the filmmaker about the sitting down so often to take in episodes of Dallas. Bergman’s funny answer: “Only the truly efficient can be truly lazy.” The filmmaker passed away in his sleep in July 30, 2007, and a private funeral ensued on Faro that followed exactly his specifications. About 70 of the invited attended, coming by ferry from the mainland, including children and actress ex-girlfriends. He was buried as requested in a white pine box.

The world mourned the death at 89 of this legendary theater director and filmmaker. Back home in Sweden, Bergman’s face would eventually appear on a 200-Crown banknote. A street was named after him in Stockholm where he often stood and waited for a taxi.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world. His latest book, Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, has been published by the University Press of Kentucky.

Tagged: God and the Devil: The Life and Work of Ingmar Bergman, Ingmar Bergman

There’s a wonderful quote by Bergman in John Lahr’s profile “The Demon Lover,” (you can find it in Lahr’s book Show and Tell):

“The wonderful thing about Ibsen or Strindberg or Shakespeare or Euripides is there is a drive, a rhythm. You feel, My God, I can listen to this. It’s fantastic. It’s breathing,” Bergman said.

Bergman, for all his flaws, strived to capture that “rhythm” in his work as a director on stage and in films. He called it “the heartbeat of a play,” and told Lahr, “It’s much easier for an audience to live with the story and accept it” when they feel that heartbeat in a production.

Excellent essay. Cowie’s commentaries for Wild Strawberries and The Seventh Seal are among the best I’ve heard. Another quote from John Lahr’s excellent profile: “When we think of Bergman’s films, joy is not the first word that comes to mind: for most viewers, they call up an atmosphere of agitation, a tense balance between scrutiny and unknowing, a sense of the silence that rustles underneath personality.Yet through this mist of unhappiness another kind of joy is discernible — in the audacity of Bergman’s camera, in the vigor of his argument against evasions of all kinds, and in the ruthless (and sometimes humorous) penetration into the contradictory drives of human nature.”

Wonderful review , Gerald. You explained a lot to me. Now, thanks to your knowledge and keen insights, I don’t have to slog through the book!