Book Review: “Get Off My Neck” — How the Judicial System Works, From a Former Insider

By Bill Littlefield

Many of the circumstances and particular cases Debbie Hines discusses in Get Off My Neck are grim, even sickening. But her experience in the American justice system has taught Hines to choose hope and struggle over despair. And that is encouraging.

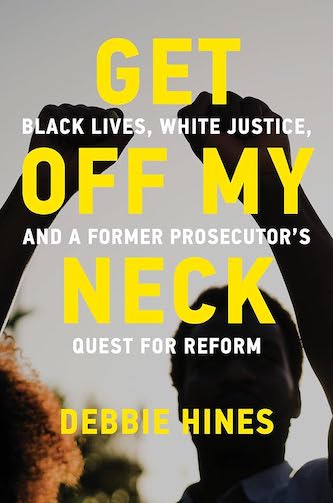

Get Off My Neck: Black Lives, White Justice, and a Former Prosecutor’s Quest For Reform by Debbie Hines. The MIT Press, 226 pages, $27.95.

Much of the information in Get Off My Neck will be familiar to folks conversant with the way the judicial system in this country operates. Of course, that doesn’t make the massive bias against Black citizens in general and Black men in particular less cruel and destructive, so it’s important that author Debbie Hines review such statistics as these: “From 2013 to 2017, unarmed Black people were 3.23 times more likely to be killed by police than were white people; Black teens are nine times as likely as white teens to receive an adult sentence; Black people are three and a half times more likely than white people to be mandated to supervised probation.”

Much of the information in Get Off My Neck will be familiar to folks conversant with the way the judicial system in this country operates. Of course, that doesn’t make the massive bias against Black citizens in general and Black men in particular less cruel and destructive, so it’s important that author Debbie Hines review such statistics as these: “From 2013 to 2017, unarmed Black people were 3.23 times more likely to be killed by police than were white people; Black teens are nine times as likely as white teens to receive an adult sentence; Black people are three and a half times more likely than white people to be mandated to supervised probation.”

These circumstances are evidence that during this country’s history racist assumptions have been built the judicial system, a system largely administered by white police officers and white officials associated with the courts at all levels.

What distinguishes Hines’s outrage against injustice and her call for reform is her background. For years she was a prosecutor in Baltimore. She didn’t merely witness the various ways in which the system disadvantages and persecutes Black citizens, she participated in that system, albeit sometimes against her will. She mentions at several points that prosecutors working trials are often directed by their superiors or by office policy to proceed in ways that feel, at best, unfair and counterproductive when it comes to public safety. At worst, such behavior is dishonest and corrupt. Hines has seen from the inside how a system bent on achieving convictions — rather than maintaining justice — can destroy the lives of people accused of crimes, whether or not they’ve committed them. Eventually she moved across the aisle to the defense table, where she now represents people like the folks she once prosecuted.

Much of what Hines feels must change has to do with the office she once occupied. As she points out several times in Get Off My Neck, often “everything in the criminal justice system – charges, bail amount, probation plea offers, probation terms, and probation revocation – is subject to the whim of an individual prosecutor.” Prosecutors who offer plea deals can threaten defendants with more serious charges and much longer sentences — if they don’t take the deals they’re offered. This is one reason so many cases never come to trial. It also accounts for many of the guilty pleas made by people who have not committed the crimes with which they’ve been charged. Moreover, prosecutors are almost never held accountable for indulging in questionable practices, some of which have been so blatant that they’ve led to reversals of verdicts. Hines is encouraged by the number of “progressive prosecutors” who’ve been elected in various cities and states over the past few years, but she warns that the system itself is still ferociously tilted against Black citizens who’ve been accused of felonies or misdemeanors.

Former Baltimore prosecutor, Assistant Attorney General for the State of Maryland, and trial attorney Debbie Hines. Photo: courtesy of the artist

The author’s greater hope rests on the “power of the people.” She is encouraged not only by demonstrations and marches on behalf of Black victims of police violence, but by “long term approaches, such as building broad bases of support among allies and working with a plan to target the levers of power.” At one point she assert that “what comes after the march may be more important than the march itself.” Hines is specific when it comes to assigning roles to “white allies”; they must not see themselves as “saviors.” She quotes James Baldwin, who maintained that it is “impossible for anyone who identifies as white to have the moral authority to lead” in the struggle for racial justice. She also references Paulo Freire’s contention that “only the power of the oppressed is sufficiently strong to free both the oppressed and the oppressor.”

The author’s concluding chapter posits “many reasons for hope.” She urges that those interested in fairness support “diversion, restorative justice, and community-based programs that address the racial trauma caused by overpolicing and overprosecution, mental health issues, and substance abuse issues.” More concretely, she recommends “declining to prosecute many of the thirteen million misdemeanor cases brought annually” and asserts that “if we took even this small step, the US carceral footprint would be mostly eliminated.”

Many of the circumstances and particular cases Hines discusses in Get Off My Neck are grim, even sickening. But her experience has taught Hines to choose hope and struggle over despair. And that is encouraging.

Bill Littlefield volunteers with the Emerson Prison Initiative. His most recent novel is Mercy (Black Rose Writing)

Tagged: "Get Off My Neck", American justice system, Black Lives Matter, Debbie Hine